Interview

PART 1

PART 2

Filipa Ramalhete

framalhete@autonoma.pt

Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa (CEACT/UAL), Portugal | Centro Interdisciplinar de Ciências Sociais da Universidade Nova de Lisboa (CICS.Nova)

João Caria Lopes

joaocarialopes@gmail.com

Atelier BASE | Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa (CEACT/UAL), Portugal

Para citação: RAMALHETE, Filipa; LOPES, João Caria – Entrevista à Marusa Zorec. Estudo Prévio 13. Lisboa: CEACT/UAL – Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa, 2018. ISSN: 2182-4339 [Disponível em: www.estudoprevio.net]. DOI: http://repositorio.ual.pt/handle/11144/3203

It is with great pleasure that we have as our guest, the professor and landscape architect João Gomes da Silva. Be welcome. We wanted to start by asking you to tell us a little bit about your academic background, what your course was like, what outstanding teachers or exercises you had.

I studied landscape architecture. I graduated from the University of Évora. During high school I was very interested in studying the forest, I was in the science field. I knew the architect Silva Dias and his children very well, made some models for him and gained a certain curiosity about architecture. At one point, Silva Dias said to me: “You have to talk to a colleague, landscape architect Celeste Ramos – with whom he collaborated – for her to explain what landscape architecture is, because it is probably something that interests you more than than architecture ”. One day we met, and it was a very immediate thing! I was very curious, she told me about what she was doing at the Sines Area Office, which was a very complex process, with several work schedules, and that interested me a lot. And I decided, in the middle of the 7th year (which was the last year of high school), to study landscape architecture.

At the time, in 1978/79, there was a course here in Lisbon, at the Agronomy Institute, which involved a study of agronomy for two years. I was not interested in that, nor in engineering – and I decided to go to Évora, where was the figure of Ribeiro Telles, who is a figure with incredible energy, with incredible luminosity! In society, and also within this disciplinary field. He had participated in the re-foundation of the University of Évora, installing the landscape architecture course in 1972/3 and I had no doubts! I ran for Évora (I tricked my parents, I told them I was running for Lisbon and Évora, but it was just for Évora) because that was exactly where I wanted to go. I was 5 years at the University of Évora, still very early in the university, and it was a very interesting experience, with a group of fascinating teachers, excellent teachers, agronomists, landscape architects, art historians – Ário Lobo de Azevedo, Eduardo Cruz de Carvalho , Alexandre Cancella de Abreu … Fernando de Mascarenhas himself was my professor of philosophy and aesthetics. I think I picked up, perhaps, the best period that the school had, which was the initial period.

It was a time when everything was still to be done…

Yes, deep down yes. Although the first generation, Ribeiro Telles, had already passed, and there was already a generation above mine, which had basically entered the local or central public administration, and there were two or three workshops. So the profession was rooted for two / three decades, but it was in full development. And, in fact, my generation – which is also João Nunes (from Proap) – starts to bet on another aspect, which is the construction of studios. Betting on the construction of a creative fabric where landscape architecture is made.

When I finished the course, I went to work for Malagueira. I went to work outside my field, for a team coordinated by the architect Álvaro Siza Vieira, with whom, in the end, I started the internship period, and with whom I continued to work for seven years. Basically, I transferred directly from the course to professional reality. In 1987 I finished the course (I already had two years of practice in Malagueira), I joined the team in a more permanent way and I was there until 1981 – in the studio that Álvaro Siza created in Évora to work on the project in the Malagueira plan. Also in 1987, I applied for an assistant at the University of Évora, in my course, and I was an assistant until 1994. I started working and teaching – I remember, when I did the interview to be an assistant, I said I couldn’t teach a project without working, my intention was to do both. Therefore, my beginning of the profession coincides not only with a professional practice, related to the project and the work, but also with teaching, as an assistant to Prof. Ribeiro Telles. I had a very comprehensive entry into my profession. And in several dimensions, one more practical and the other more theoretical.

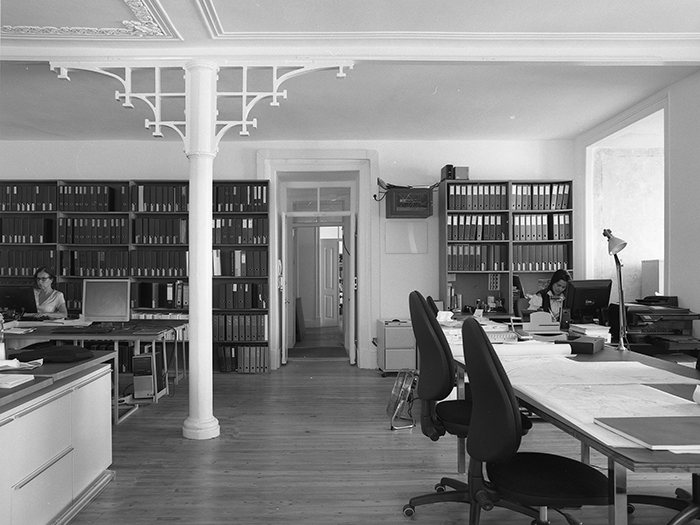

© Pedro Frade – Todos os direitos reservados

And when do you create your own studio?

A little later. In 1991, I made a contest with Inês Norton and João Sousa Mateus, for the Schinkel Prize, in Germany. We won this award, which created public and professional visibility and gave us a certain boost. And it was from there that we started to make a studio, which was something that hardly existed in our area. In 1994, I stopped teaching. I had my first daughter in 1993, and I made a decision, which was to leave Évora, come to Lisbon and focus exclusively on the studio. This coincided with another work cycle. I was collaborating with Siza, until 2002, but I started another cycle, which was to have a studio and start collaborating with many other architects. It is a theme of my life, collaboration.

In 1994 … And when did you enter the Autonomous University, as a professor?

As is usual, I started with a “mansinho”… In the end it was João Luís (Carrilho da Graça) who called me, me and Inês Lobo, who was working as an assistant. I had already collaborated with Carrilho da Graça, first asked me to go criticize, then to go to a class… And there is a moment when he invites me to give a course, still in the pre-Bologna system, in the 5th year .

© Pedro Frade – Todos os direitos reservados

And do you want to talk a little more about the topic of collaboration? In 5th grade, you also focus your teaching a lot on this idea of collaboration…

Collaboration is a kind of longitudinal theme to my professional life!

Before going to study landscape architecture, in fact, somehow I was in the environment of architecture studios, but I was not an architecture student, nor do I have any kind of family or professional relationship, in my family, with architecture. The theme of collaboration arises from a knowledge, which I have, since very early, of what activity in Architecture is – for these practical reasons, of making models, of helping to assemble things …

When I finished the school part of the course, I had a professor of urbanism, Architect Paulo Gouveia – who has already died – and who was my teacher and then he was my colleague. And he takes a class on various plans that were taking place, in Sines, in Santo André, and in Malagueira. Invites architect Siza, who was not available, and Nuno Ribeiro Lopes went to present. I remember that the presentation was fascinating. We were in Évora, we saw what was happening, (in 1983/84) and, at the end of that class, in the question and answer phase, I asked what was happening with all this landscape, which is created and that turns over there – “Is anyone working on it? We are here in a landscape architecture department… What is going on? ”. And, in fact, nothing was happening yet. I then make a contact and offer myself as an intern. There is an interview and this interview goes quite well – it was a conversation with Siza, who went to Évora weekly – and I start to collaborate. And I start to collaborate in a very intense way and that is very decisive for this theme of collaboration – of course, on the side of my department, they say that I am going there alone, that I was in the hands of an architect and that it put me in a fragile position.

It is in this way that the subject of collaboration comes almost from a conflict; not in the bad sense, but in the sense that there are visions that do not overlap. Therefore, I do my internship in a field and in a space for discussion and production that is from another discipline, where I have to be responsible for proposing disciplinary views.

And, in fact, all the contact I have with Álvaro Siza, with Nuno Ribeiro Lopes, and with all the architects that collaborate in this plan, is very stimulating. And I realize that what I am bringing to the discussion and analysis of the problems that were arising are topics that are of great interest to everyone, especially to Álvaro Siza, with whom I later began to collaborate in a more intense way.

The first thing I remember… He gives me a pile of sketches and photocopies of his notebooks and says: “Look, these are my ideas about Malagueira, about the outer space, the open spaces… Tell me what is that you think. For the week I come here and tell me what you think about this. Because this is a starting point, for me. ”

And I, in fact, have been reading all the drawings and, deep down, it was an imaginary, what he passed on to me… And when he returned I said to him: “I think it is a set of references, which I recognize in my own experience here in Évora, and I have something to propose, which is to go for a walk. ” And what did we do? We climbed up the valley, Malagueira is a transept in the valley of the Turgela stream, and we went up this stream and visiting several recreational farms. In the end, it was the noble periphery of the city, where there were farms, houses, irrigation systems with gutters, tanks and tiles, all this theme … And I was explaining how that landscape had been formed and what it was that Malagueira represented in that sequence, centered on the riverside – Malagueira, in fact, corresponds to a transept, a cross section on this natural reality, which is opposed to an urban axis, which points to the center of the city. He said that everything he was saying was very interesting, found an approach that interested him, and started to involve me.

And a fascinating work process started for me. It was a kind of revelation. Because, from the scale of planning to the scale of the project and the scale of the work, everything has unfolded. With demands for community participation, associations of residents … The theme of participation, which has been talked about a lot in recent years, was almost a requirement there, even for political reasons.

So, for me, the theme of collaboration started in this way, very intense. And when I was told I was disappointed, I said no. I do not believe that there are enmities between similar disciplines. I think there is a huge contact zone, and it is in that intersection zone that I want to position myself. I am not interested in encapsulating myself, I believe that between architecture and landscape architecture there is an immense potential for development, production and, above all, creation. And that is what I have done throughout my life, over these almost thirty years. It was, fundamentally, to believe that the reality is so complex that there is not a single discipline that achieves specialization. Modern knowledge has taken us away from a fundamental thing that was being able to submerge again in various perspectives and being able to look at problems from their complexity and not from their dismantling, which is what the paradigm of knowledge defends modern.

© Pedro Frade – Todos os direitos reservados

In that sense, were you a different teacher when you were teaching landscape architecture students and now architecture students?

This poses very big didactic and methodology problems. I teach at Autónoma, in a class of finalists. They are students of architecture, so they are students who do not have basic training on landscape issues. As I teach the students of Mendrísio, where I am also a teacher. In fact, I am teaching at “someone else’s home”. And I do it with immense pleasure, despite knowing and feeling that there is a huge limitation from the methodological point of view, due to the fact that I am dealing with people who do not have a background that allows them to understand things in the same way. And I have to be able, in a partly empirical, partly instrumental way, to dismantle reality and help to create the capacity of an architecture student to be able to understand landscape as space, more than as an image, a scenario where things happen – which is the vision that traditionally exists. My view is that the landscape is space, it is architecture, it is construction. It is the construction of a space in the territory. Sometimes I say, in a simplistic way, that the landscape is the architecture of the territory.

Two years ago I was a visiting professor at Harvard University, at the Graduate School of Design, and then I started teaching landscape architecture students and architects again, and I felt that, in fact, working on the project there has another potential. We can go much more deeply, addressing other issues.

But, returning to Autónoma, the work I try to do is, first, to create language, notions, meanings – which is fundamental when we want to deal with a certain theme. Second, to create a critical vision – to propose to students that they begin to look critically at the space and begin to interpret it. And, for that, there are certain exercises of representation, which necessarily lead to an analysis. Thirdly, we are working, in some way, on a fundamental theme of architectural design, which, in this aspect, has to do with the ideas of location and implantation – these are two fundamental themes for architecture, especially the issue of implantation – it is a theme that Vitrúvio defines as one of the principles of architecture. The location theme requires a more territorial scale and the implementation theme a more local scale. Basically, what I do in the second semester with my students is to make them look critically at the project they are developing in the Project discipline. And what I try to do is move them to an area of discomfort, get them to look at their architectural project in another light – which is the choice of a place, the relationships that are established and the transformation of the place through deployment theme.

And it adds to all this, the theme of collaboration…

It is evident that I try to continue explaining what are the potentials that are being created there and that obviously could be deepened. Just as, of course, they feel the need to go and talk to the Structures teacher, because they realize that the fundamental idea of the project needs a view of physics, of statics and, therefore, they will look for the teacher.

In Mendrísio the same thing happens, albeit in a more institutionalized way, because the school designates, in each area of knowledge, a teacher who has to provide tutorial assistance to students who are developing the final project. Basically, informally, that’s what happens at Autónoma.

© Pedro Frade – Todos os direitos reservados

The profile of our students has changed a lot in recent years, and your experience with students from other countries, leads me to answer – the landscape being also a cultural construction – if it is a different challenge, working with students, referring to references are not the same. In other words, teaching students from different countries, with different backgrounds, poses new challenges?

Get up, because half of the students I have at Autónoma are not Portuguese. Some bought from Africa, others from Europe … Many from Italy, Spanish, Northern Europe, Norwegians … The knowledge that students have, that people, in general, have about the landscape is empirical. It is about your life experience, we transport what we build on our life experience. We all have a kind of mental construction, an imaginary that we build on what a landscape is, either because we live in it, or because we travel, or because part of our family is elsewhere … This knowledge makes us build this kind of memory, that structures us and stabilizes our view of the world. From our memory, we are constantly interpreting reality and analyzing it, even if we do it unconsciously. And therefore, what the university has to do, and this is what distinguishes it from intermediate training, is like people so that, in a certain degree of abstraction, they are able to confront reality. What a university does is to equip us with a certain capacity to be able to look at the world, to relate to it, to improve it, to be able to intervene in the world and transform it. That’s what an architect does. It is to transform the world!

At a certain point, Siza, when asked how a Portuguese architect was doing houses in Berlin and Holland, he said: “In fact, I always carry my ghosts, my references with me. But in fact, in Holland, I am not working for a community of Dutch people, but of Turkish immigrants. And I have to be able to understand their way of life and I have to invent an architecture where I am able to synthesize all these communities.

And I think this is very true. What is this about Portuguese architectures? These are questions that have always been discussed a lot and have many answers… This is to say that, in fact, what I hope is that students who leave school will be able to locate themselves anywhere in the world, and that they will be able to create , regardless of where they are, always considering their memory and their roots, being able to intervene in these realities.

This is a kind of ambiguity that seems to me perfect for explaining what our role in the global world is.

I was wondering if I knew of any publication on landscape architecture… There is very little dissemination of landscape architecture projects, at least compared to architecture… I remember that it was only in the 1st year of my PhD that I read the article Terra Fluxus, by James Corner , for example. The amount of information that comes to me about landscape architecture is very little.

It has its circuits and its specifics. I would say that there has already been a lot more communication, but this is the same for architecture. When I say communication, I mean communication structured in the form of regular publications. In Europe there are several magazines that, in the end, are the references, that had their golden period and that today are much more reduced. There are also many websites online, there is a well known one called Landzine.

Now the problem that arises in relation to landscape architecture and also arises in architecture and other arts, is that, although we have much more information available, that information is much less filtered, structured, criticized. And, in fact, we have more and more information, but it is information of a generic nature, to the point that today it is very difficult for a student, and I am talking about 5th year students who should already have some experience, have a critical view on the information they collect on the internet. So much so that at some point I had to force them to define the origin of these sources and the veracity of the information, given that there is a certain loss of consistency and critical view of the amount of information that is available.

By the way, I ask you what is your relationship with research in your practice?

I think that all architects who do design can do research. I do not say that everyone does it because many of us, at certain times, are not investigating anything, we are just reproducing models, archetypes, or projects that we have already built and that we think are replicable … Sometimes we face new problems and we have to investigate. And that research is done in workshops and not in universities. This brings us to the problem of what is research in architecture, or landscape architecture. When we are in the domain of theory, of history, this is easy to answer. When you move to architecture itself, as a practice, things start to get much more difficult.

I had the chance to attend a conference in Mendrisio by two Swiss architects (Burkhalter and Sumi) who were celebrating this year, who made a remarkable presentation on the research they had done over the past twelve or thirteen years in the Academy, in a classroom setting, with his students, and to what extent this had built a body of knowledge relevant to the school. They systematically did the same exercise with the students, which consisted of representing with the same representation technique a series of works, almost all modern, trying to explain the relationship between space, structure and infrastructure. And they made a set of diagrams, which started from the representation of the structure in section, and then in perspective, of the installations and always used the same graphic system. And what is a fact, is that, after these 13 years, they were able to group a set of buildings that they had analyzed and create a kind of typology about this relationship between space, structure, light and infrastructure. And I found it truly evident and clear, for the first time, what it means to investigate architecture.

© Pedro Frade – Todos os direitos reservados

Is there current research that influences the studio’s projects?

There is. And I think it was easier and now it is more difficult because there is a kind of slowdown in the production of architecture. Deceleration, because we had a decade that fundamentally reproduced canons. In Landscape Architecture this is very evident. If we start to see what has been published in the past two decades, we realize that there are key projects that, at a given moment, point out very interesting paths. We recently spoke about James Corner, and there is a particular work of his where, for the first time, the construction of a park is made from the attempt to incorporate water purification systems, technologically fundamental space in the life of a city or a city. region – and he proposes the reconfiguration and integration of these spaces in the organization of a park. We have the product of this archetype here in Lisbon, in the Tagus and Trancão Park, by João Nunes (from Proap in collaboration with George Hargreaves), in which a landfill and a water treatment plant are part of the design and structure of the park, and, if there had been a third part, this integration between infrastructure and landscape had been even more consequential, spatially. Like a collaboration that his studio has with Manuel Aires Mateus and an engineering group, transforming a WWTP into a work of urban landscape. Not being a public space, it is still a fundamental and referential space in the Alcântara Valley. Therefore, there are in fact archetypes that exist because they were allowed to reflect on reality and propose something new, a new model, a new type of space organization, a new expression. And I would say that we have been less requested for reflection on reality and more for mass production – but this had to do with a time when there was an enormous accumulation of capital and there was the possibility of carrying out works that repeated models and that, bringing nothing very new, disseminated another quality. I would say that now we are in another cycle. Less means, we no longer produce in the same way, the objectives are no longer the same.

The type of order I have at the studio no longer has anything to do with what I had a few years ago. We are currently working for agriculture companies. We have two or three projects carried out in agrarian space, in productive spaces, in vineyards, viticultural landscapes. Reformulate these landscapes, introduce the function of wine tourism, which is an important function for the economy of these production processes, ecologically improve the production process itself, solve water treatment and drainage problems, organize the work space, segment visits … These are themes that 10/15 years ago did not exist.

I was trained at the school in a rural landscape environment, with all the problems that existed then. Today the problems are completely different. If there is any sector where there is a huge investment, it is precisely in the productive landscape. And I would say it is an incredible field of work.

There were, in fact, in the field of Landscape Architecture, two or three important moments in the last two decades, which produced some very interesting works – works of text collections. One of them, I think, is the one with the text you were talking about, Terra Fluxus, by James Corner. And I would say that it has been possible, in these last two decades, to reconstruct a theoretical body, not already modern, but contemporary, and I think that there are two or three works that are fundamental to expose what is contemporary Landscape Architecture.

One is the Recovering Landscape, where this James Corner text is, another is a compilation of articles by various authors, Theory in Landscape Architecture: a reader, by Simon Swaffield. In fact, it is one of the books we use at UAL.

This is to say that there are cycles of certain progress and construction and then there are cycles of certain reproduction. And I think that we are reaching a kind of end of cycle, at a time when we ask ourselves: “what is it for?”

© Pedro Frade – Todos os direitos reservados

In landscape architecture, there are also movements similar to what you are seeing in architecture, which is the small scale, the informal, the local, the participatory intervention? Is this also a trend in landscape architecture?

Somehow, yes, although the problems are put in a slightly different way… One of the things I try to work with students is this notion between the local and the global, or between the local and the regional. Which are themes that, in Landscape Architecture, are not separable, and that are very different in relation to the approach that in UAL or Mendrísio, is made in relation to space. Approximation in architecture is done in a very objectual and non-contextual way, despite Contextualism being one of the identity matrixes of Portuguese Architecture of the last three or four decades. For Landscape Architecture, the context is Landscape. The Landscape is container and content. There is a very interesting text that he used to give students to read, which is from Christian Norberg-Schulz – Genius Loci, Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture, where he talks about this double condition of Landscape, between container and content. And there are aspects that are discussed a lot in Architecture that are fundamental for Landscape Architecture, at least since the 1950s / 60s when there are immense parallels, because the Modern culture of the disciplines of Architecture and Landscape-Architecture has a lot in common. Modern roots of Landscape Architecture are often the same, although they are not grown in the same places, in the same schools.

And are there any new or more recent workshops that you accompany? Who are doing interesting projects?

Somehow yes. In Portugal, the crisis did a terrible thing, which was the destruction of the productive fabric of our creative area. There were a lot of ateliers that closed or were dying … Mine also went through this brutal crisis. First it was built, we spent twenty years building it. Then we spent four or five years deconstructing it, and deconstructing it means abandoning, separating myself from people with whom I had built a common practice… but they generated other workshops. And I am delighted to see that there are workshops that are being built from scratch, that have started from other workshops. This means that there is a kind of reproduction of the productive system, it was something that my generation started to build systematically. So yes, there is a regeneration, as I think it happens in the field of Architecture. I collaborate and have always collaborated with architects from a generation above my own, but I also collaborate with architects much younger than me, and that makes me have a very privileged view of reality, I understand what is going on – and I like it!

© Pedro Frade – Todos os direitos reservados

It is always difficult to make predictions these days, but what trends do you see happening? What would you like to say to architects who want to collaborate with landscape architects?

There is one thing that I think I have cultivated, and my colleagues from the same generation tried to do the same, which was to cultivate this practice of collaboration. And what does that mean? It means that we have to be able, without giving up our points of view, to put ourselves in the point of view of others in order to better understand what we are trying to discuss in common. In other words, decentralize from our creative practice, decentralize from our perspective and be able to get out of ourselves and focus on the object we are working on. And to do it in a generous, confident way and above all to be able to discuss a particular problem freely and openly, benefiting from the views of others and being able to put ourselves in the view of others. This is what I call the practice of collaboration.

There is a very interesting text from an interview with Jacques Herzog and Pierre De Meuron, for many years, in which they talk about the collaboration they had with Rémy Zaugg (an artist who has died), and also about what they were absorbing from another artist fundamental to their practice, who was JosephBeuys, and who left a deep impression on me. And so this issue of collaboration (and availability for collaboration) is what I wish for all emerging architects and landscape architects, who able to promote as a common culture. It is being able to, without suspicion and without ulterior motives, genuinely and naively, to open up and make themselves available to collaborate. This without losing their specificities and capabilities, as we should never give up on that. I hope, even if that spirit is something that never disappears or does not turn into anything negative, because it took a lot of work to create this mutual trust and it is very easy to lose it. But I am optimistic, always! Now is the time to be optimistic!