João Quintela

joaopedroquintela@gmail.com

Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura – Universidad Politécnica de Madrid | CEACT/UAL – Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa | Professor auxiliar convidado do Da/UAL | Arquiteto

To quote this text: Quintela, João – The disagreement between Otto Wagner and Gottfried Semper: a question of detail. Estudo Prévio 17. Lisboa. CEACT/UAL – Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa, 2020. ISSN: 2182-4339 [Available at: www.estudoprevio.net]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.26619/2182-4339/17.03

Review received on 25 June 2020 and accepted for publication on 17 July 2020.

Creative Commons, licença CC BY-4.0: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

The concept of tectonics in modern architecture dates from the end of the 19th century and is linked to Karl Bötticher (Nordhausen, 1806 – Berlin, 1889) and Gottfried Semper (Hamburg, 1803 – Rome, 1879), among others. In a recent interview, architect Kenneth Frampton (Woking, 1930- ), who dedicated most of his research to this topic (1983, 1990, 1995, 2005) and has advocated tectonics as the “potential of constructive expression”, referred to a specific event when Otto Wagner (Vienna, 1841 – Vienna, 1918) revealed his disappointment towards his master, Gottfried Semper, because he no longer gave primal focus to structure and constructive expression. For Wagner, art-form could only be designed from construction, which places him closer to the theoretical framework of Karl Bötticher.

This paper discusses how the concept of tectonics developed in the transition from the 19th to the 20Th century, analysing the differences between Gottfried Semper and Otto Wagner as presented in his book “Moderne Architektur: seinen Schülern ein Führer auf diesem Kunstgebiete” (1896), and focusing on his analysis of the building of the Postal Savings Bank (Vienna, 1905). In this project, Wagner places in practice his theoretical considerations that construction detail is able to link the core form and the art-form, two concepts that can still be applied in contemporary architecture.

Keywords: Otto Wagner, Gottfried Semper, Kenneth Frampton, art form, core form, tectonics

1. Introduction

“The herd must distinguish themselves by the use of various colors, modern man uses his clothes like a mask. His individuality is so strong that he does not need to express it any longer by his clothing. Lack of ornament is a sign of spiritual strength. Modern man uses the ornaments of earlier and foreign cultures as he thinks fit. He concentrates his own powers of invention on other things.” (Loos, 1908)

Architect Adolf Loos (Brno, 1870 – Vienna 1933) uses these words to finish his text Ornament and Crime, dated from 1908, one of his most relevant theoretical texts, whose influence is still present today. Written in an ironic tone and with such acumen, the text was only published in German in 1929 by the Frankfurt newspaper, having by then been disseminated in almost all languages (Loos, 2004: 234).

At a moment when contemporary architecture production is confronted with a return to ornament in its multiple approaches, and mainly as a means to attain formal and symbolic expression of architectural object, it appears inevitable to revisit the theoretical and practical context at the end of the 19th century, namely, the debate on ornament and its relationship with structure and the constructive system. We will do that through Otto Wagner, specifically through his theoretical reflections, in which we can find some criticism to Gottfried Semper. These considerations would be materialized more explicitly in his project for the Postal Savings Bank, built in Vienna between 1904 and 1906. The building’s façade evidences a clear shift when compared to his previous works and represents the result of some research he had been gradually conducting in previous designs. In this project, the author clearly aims to clarify the concepts of “art-form” and “core form” and mostly how the coordination between the two may become an expression of a unique architecture of its time (Wagner, 1993). Art-form would be linked to ornament and the symbolic meaning of the building, whereas the core form would be linked to structure and construction.

2. ‘Moderne Architektur’: acknowledgment and criticism to Gottfried Semper

One of the most important factors accounting for the relevance of Otto Wagner in the history of architecture lies in the fact that he designed a theoretical key work that would eventually clarify the debate on the right way to appropriate style, a debate that had been going on for decades, as well as define a set of premises that would lead to the onset of modern architecture in the next few years (Wagner, 1933).

“was the first modern writing to make a definitive break with the past, outlining an approach to design that has become synonymous with twentieth-century practice. Historically, however, it may be more accurate to view the work as the culmination of nineteenth-century efforts to create a new style” (Mallgrave, 1988:1).

In his text, Moderne Architektur, Wagner left a series of reflections that would allow for a better understanding of his work and contributed to architectural heritage. His influence on the students attending the Akademie der bildenden Künste in Vienna led to the famous Wagnerschule which included some of Wagner’s followers and former partners, such as Josef Hoffmann (Brtnice, 1870 – Vienna, 1956), Joseph Maria Olbrich (Opava, 1867 – Düsseldorf, 1908), Josef Plečnik (Ljubljana, 1872 – Ljubljana, 1957) or Max Fabiani (Komen, 1865 – Gorizia, 1962), who continued his research on new technical and artistic conditions in architecture and on how these could lead to a new architectural style that would, in this specific case, reflect mostly on the façade and the symbolic character of surface.

The book was first published in 1896 and again in 1898, 1902 and 1914, each edition carefully revised by the author. Besides writing the preface of each edition, Wagner introduced changes to the text at several levels, from replacing some words to introducing new chapters to, in the last edition, replacing the title to Die Baukunst unserer Zeit (Architecture of our time). Several authors have analysed the differences between the four editions, since they allow us to better understand how Wagner’s thought changed and how these changes correspond to his work (Mallgrave, 1988). One of the least referred elements but which we deem relevant to the topic under analysis are Wagner’s references to his master Gottfried Semper.

If we analyse the different editions, we realize that there are small changes or clarifications that provide us clues to understand his thought process. As Henry Mallgrave states, “in the 1898 edition Wagner deletes the adjective from the phrase “Semper’s immortal design” (1896 edition), thus chronicling Semper’s decline in popularity around 1900” (Mallgrave, 1988: 60)in reference to Semper’s design evidences Wagner’s increase distancing from Semper, which is also emphasized by Kenneth Frampton in an interview, when he affirms that. This omission of the adjective “immortal” the book criticizes Semper for not continuing to consider structure important “it contains a criticism of Semper because from the point of view of Wagner, Semper in a way doesn’t keep the importance of structure ” (Frampton, 2020).

If we analyse the first version of Moderne Architektur we find positive references to Semper, some of which are deleted in later revisions. An example of this is in the first chapter, when Wagner talks about the role of the architect

“Hans Makart, for instance, possessed more innate ability than acquired knowledge, while with Gottfried Semper the reverse was obviously true. Because of the enormous amount of study material that the architect needs to absorb, the Semperian relation in most cases prevails” (Wagner, 1993: 35).

This paragraph would be deleted in 1914, at the same time Wagner adds two new chapters, one on promoting art and another on criticizing art. In the latter, Wagner criticizes Semper’s project for the Vienna National Theatre, in which, according to Wagner, some elements are disproportionate when compared to the whole project and the polygonal foyer is described as “an aesthetic disappointment” (Wagner, 1993: 168).

It is in the fourth chapter of Moderne Architektur that we find the three key moments that help us understand Kenneth Frampton’s previous statement. This is a chapter on construction, a chapter many see as the core point of Wagner’s theoretical work (Mallgrave, 1988: 29(. Wagner mentions here some of the topics he will later explore in some of his urban buildings and his most important work, the Postal Savings Bank. It is not by chance that it is here that Wagner includes his highest praises and his fiercest criticism of Semper.

Already in the first page, Wagner claims that

“Need, purpose, construction, and idealism86 1 are therefore the primitive germs of artistic life. United in a single idea, they produce a kind of “necessity” in the origin and existence of every work of art, and this is the meaning of the words “ARTIS SOLA DOMINA NECESSITAS.”. No less a person than Gottfried Semper first directed our attention to this truth (even if he unfortunately later deviated from it), and by that alone he quite clearly indicated the path that we must take.” (Wagner, 1993: 103-104).

Wagner acknowledges Semper’s relevance because he paves the way to the new generations; yet he also criticizes Semper’s inability to place in practice his theoretical project.

This idea is later further discussed, when Wagner states that:

“It is Semper’s undisputed merit to have referred us to this postulate, to be sure in a somewhat exotic way, in his book Der Stil. Like Darwin, however, he lacked the courage to complete his theories from above and below and had to make do with a symbolism of construction, instead of naming construction itself as the primitive cell of architecture” (Wagner, 1993: 106).

Wagner was convinced that construction in itself must be the starting point for any architecture design and not its symbolic representation, as Semper had advocated. Wagner makes it clear that “Construction always precedes, for no art-form can arise without it, and the task of art, which is to idealize the existing, is impossible without the existence of the object” (Wagner, 1993: 106).

Near the end of this chapter, there is a third reference to Semper, included in a part of the text on solid construction methods for fast building, which are typical of modern architecture, and which should be correctly used. Wagner starts by stating that the architect has two main tasks. The architect must present art-form with constructive clarity while showing people that these art-forms are correctly expressed depending on the materials used, otherwise there would always be some sense of trickery or disquiet “a certain degree of deceit or restlessness” (Wagner, 1993: 84).

When talking about these constructive methods, namely their economic advantages and expressive qualities, Wagner analyses a specific example which he only identifies in the 1914 edition – the Vienna National Theatre, designed by Gottfried Semper and Karl von Hasenauer (Vienna, 1833 – Vienna, 1894). According to Wagner, the use of stone in this building represented an excessive waste of time and money and, as such, it should be described as an error “a way of building that we should define as not right” ” (Wagner, 1993: 85). Next, to substantiate his argumentation, Wagner talks about an example of modern construction method and, though he does not reference any of his own projects, he describes the solution he used and applied in many of his buildings – stone plates as cladding. “Since these panels can be assumed to have significantly less cubic volume, they can be designed for a nobler material (for example, Laase marble). They are to be fastened with bronze bolts (rosettes).” (Wagner, 1993: 109). When concluding this comparison, Wagner states that the second option would reduce stone cubic content in about a fifth when compared with Semper’s project. However, the impact would be much higher because a more noble material would have been used in a shorter construction time.

According to Kenneth Frampton, Wagner’s disapproval disappointed is because of the neoclassicism of Semperian architecture, particularly when he goes to Vienna and is a partner of Karl von Hasenauer (…) a kind of late nineteen-century neoclassicism which of course to some extent he had already used in the Opera House of Dresden when he first works for the court. I think he is recommended for that position by Schinkel by the way. But the important thing is that Wagner expresses his disappointment with Semper because Wagner is preoccupied with the expression of the structure. Of course, there’s also ornament in Wagner but if you think of the Postsparkassenamt of Wagner, a very important building, the stone cladding – bekleidung – is impregnated with metal, so Wagner tries to express the essential structure that is of steel”.

This statement leads us to confirm that Wagner’s disagreement with Semper lies exactly in that understanding of the concepts of core form and art-form and especially in the prevalence of one over the other. For Wagner it is obvious that “the architect always has to develop the art-form out of construction” (Wagner, 1993: 106) and art-form is firstly expressed in the façade of the building.

3. Constructing art-form in the Postal Savings Bank

Viennese architecture in the transition of the 19th to the 20th century evidences that special attention was given to façades. This is a period of social, political and technological change and the transition between public and private space was seen as a cultural and ideological manifestation of the city’s design, one which gave it an extremely relevant symbolic character. The surface of the cladding would evidence the building’s character in the same way clothes revealed a person’s social status. The surface as a metaphor of clothing (Bekleidung) derived from direct interpretation of Gottfried Semper’s writings and, in particular, from the relevance given to the book “Der Stil in den technischen und tektonischen Künsten oder praktische Ästhetik: Ein Handbuch für Techniker, Künstler und Kunstfreunde” (1860).

However, if we analyze works by Otto Wagner, Josef Hoffman, Max Fabiani or Josef Plečnik we realize that different Viennese architects understood Semper’s theory on cladding differently. Two of the most obvious examples to understand those differences are the Palais Stoclet (Brussels, 1911), by Josef Hoffman, and the Postal Savings Bank (Vienna, 1906), by Otto Wagner, which will analyse in detail later in the text. Eduard Sekler classified the Palais Stoclet as “atectonic” because it revealed such a degree of abstraction that all the details invoked the negation of construction in favour of the sublimation of form (Sekler, 1967). The will to annul construction expression is evident, especially if we analyze the corner of the building where two exterior plans meet. In the contact point between these two surfaces covered by marble plates, Hoffman introduces a black and golden metallic element, similar to a textile rim that spreads to all the edges. Ornamentation, in this case, art-form, appears and annuls constructive joint and hide the thickness of the marble plate, thus not allowing tectonic expression to reveal as much as constructive technique in terms of structural logic (Figures 1, 2).

Figure 1 – Palais Stoclet, Josef Hoffmann (1911), Overview. Unknown author.

Figure 2 – Palais Stoclet, Josef Hoffmann (1911), detail from the façade. Unknown author. Source: Leatherbarrow, 2007: 94.

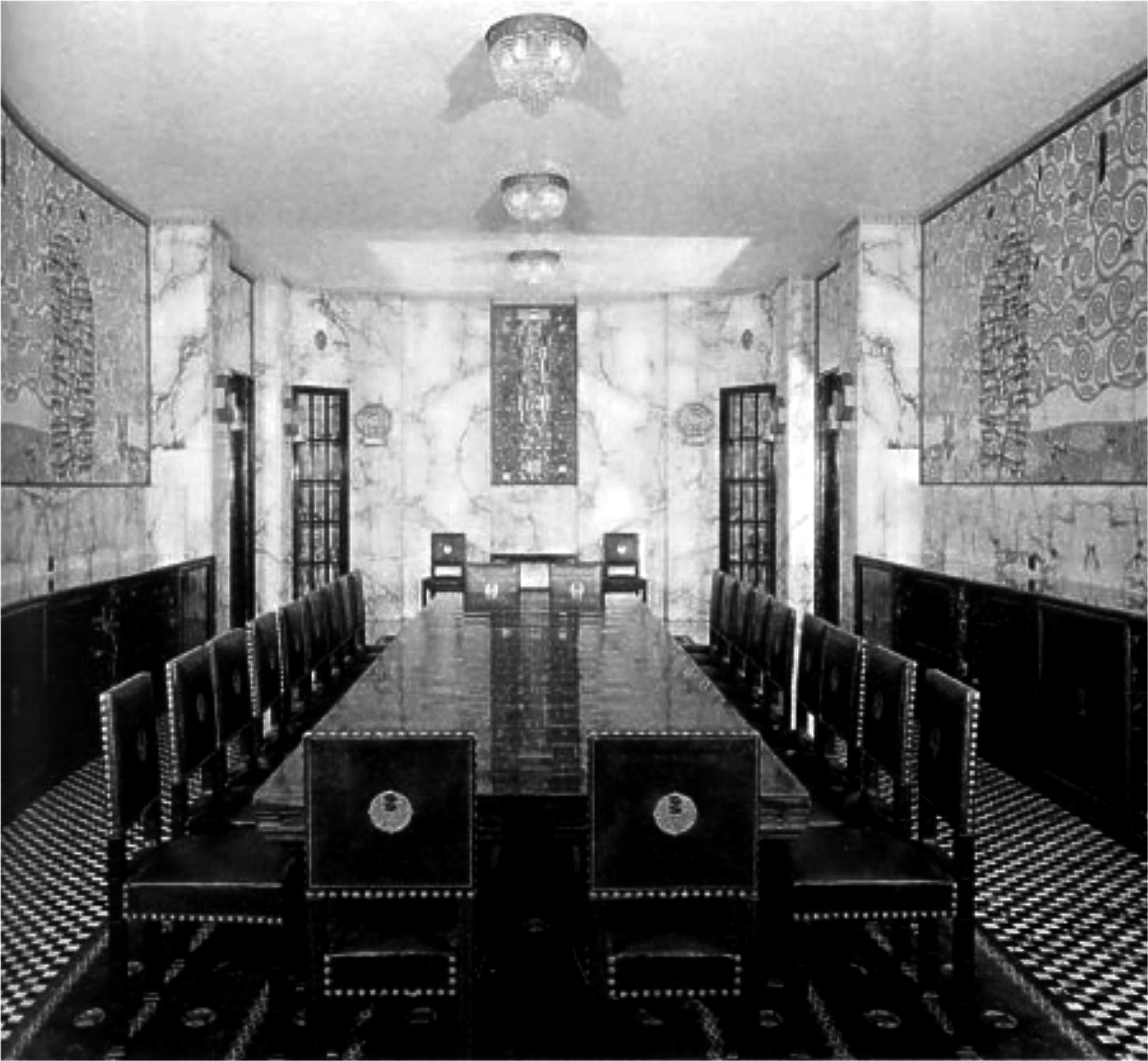

This approach does seem to be closer to Gottfried Semper’s ideas than in the case of the Postal Savings Bank, especially if you consider his words in ‘Der Stil’. In the chapter on textile art, Semper claims that annulling the material is needed when you consider that form should appear as a symbol “the rejection of reality, of the material, is necessary when one considers that form must appear as a symbol, full of meaning and, simultaneously, as an autonomous creation of Man. We must forget about the means used to achieve the desired artistic effect” (Semper, 2014: 309). We understand why Hoffmann aims to hide the thickness and fastening of the marble through an ornamental element that evokes tapestry. This way, it establishes an analogy with the textile world, which, according to Semper, would be at the roots of architecture (Semper, 2014: 298). We can also realize that the spans are aligned with the exterior of the façade to avoid any idea of depth and are also rimmed by the same ornament that hides the joints of the marble plates at this point. Hoffmann wants to tell us that those exterior walls are not thick but are suspended tapestry elements. The technique is just a means to achieve the artistic effect and, as such, it is not an expression. The same occurs inside of the building, where constructive elements such as pillars, beams or arches are covered by thin stone plate. The flat effect of these surfaces is reinforced by the paintings by Gustav Klimt (Vienna, 1862 – Vienna, 1918), a friend of Hoffmann and one of the most influential figures of the Viennese Secession (Fanelli, 1999: 95), (Figure 3).

Figure 3 – Palais Stoclet, Josef Hoffmann (1911), view of the interior. Unknown author.

Giovanni Fanelli and Roberto Gargiani state that Semper’s texts in Der Stil are in favour of annulling reality ad hiding materials through masking. However, from a theoretical perspective, Semper considers that masking always implies mastering the technique, which has led to apparent contradictions “between the vocation of the «Nutzstil» as a way of applying modern technologies or as a concrete manifestation of the Semperian ideal that proposed the symbolic transfiguration of constructive reality” (Fanelli, 1999: 66). It is precisely this that allows us to better understand the differences in understanding between Hoffmann, who tried to achieve the symbolic change of constructive reality, and Wagner, who was focused on defining a modern style that would derive from new materials, new building technologies and new constructive systems. Again, we can deduce that, in Hoffmann’s case, primacy is given to the symbolic expression of art-form, and in Wagner’s case, that primacy is given to constructive expression of art-form.

In April 1894, two years after the first edition of “Modern Arkitectur” Wagner is appointed architect of the Stadtbahn, Vienna’s new railway system. For six years, Wagner develops a project for more than 40 metro stations, bridges or viaducts and is confronted with economic limitations and functional demands (Mallgrave, 1988: 27). The infrastructural component of this large-scale project had a major impact on Wagner’s future work and drew him closer to engineering and new iron and concrete structural systems.

“Wagnerian considerations about the «platternverkleidung» with exposed metallic fixation were formulated at the time when Wagner was developing the projects for the Vienna’s metro and, from 1894, he was faced with technical and formal problems in the relationship between construction wall and metal structures. For this articulation, the fixation through metallic elements assumes a decisive symbolic importance.” (Fanelli, 1999: 74)

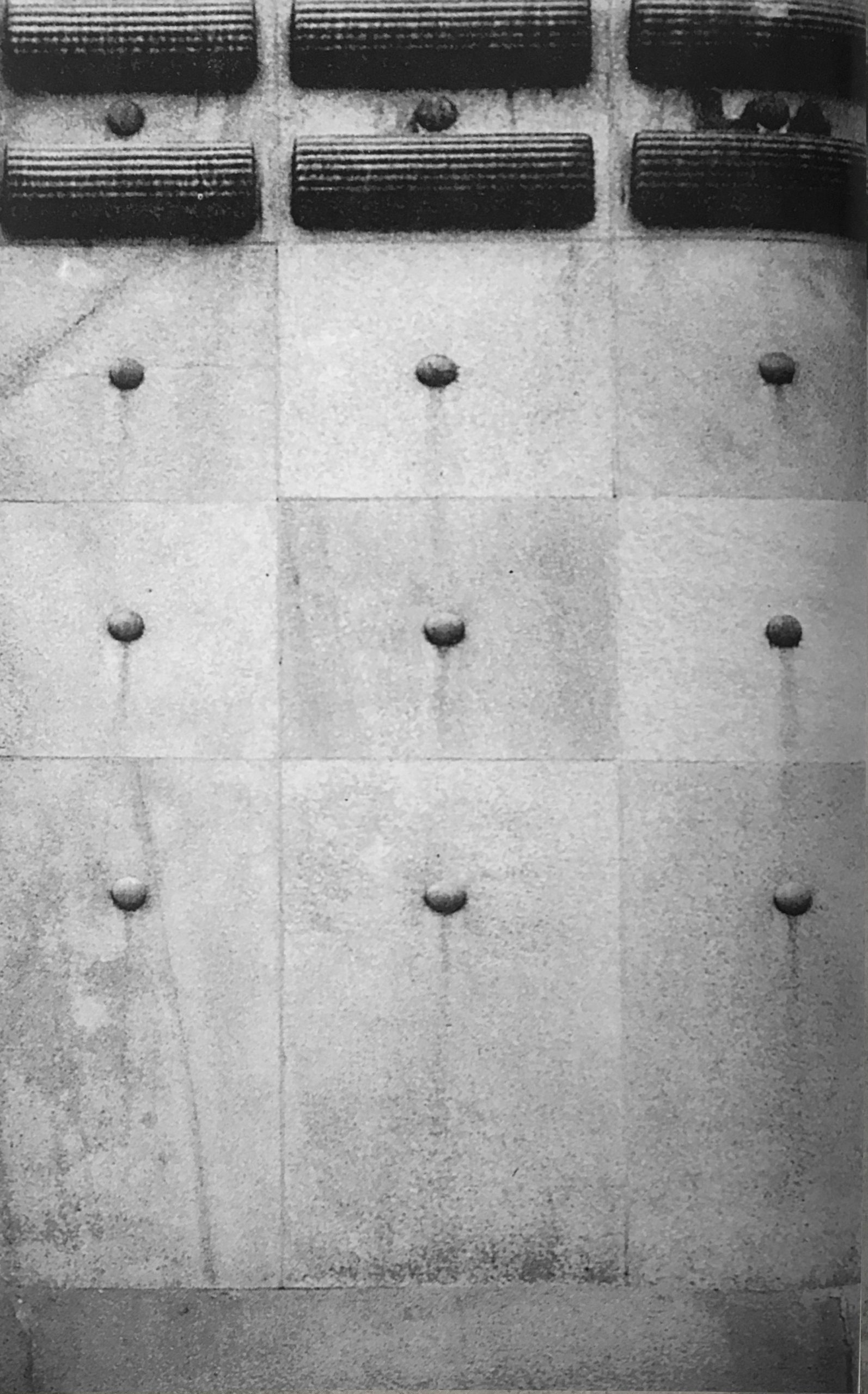

In fact, it is in the Karlplatz metro station (Vienna, 1898) that, in 1898, that Wagner first conducts research on the expressive potential of visible metallic fasteners. These are the only projects by Wagner that were built using metal structure and in which there is a clear intention to reveal the static function of its elegant skeleton. This is made evident by its exterior, in contrast with the thin 2-centimeter marble plates that fill the void between the vertical elements (Figures 4, 5 ad 6). The cladding is not used as a means of hiding the material or the rhythm of the structure, quite the opposite, we are able to see its non-structural feature. However, the most significant is undoubtedly the way in which Wagner aims to express that feature through the metal circles on the top of the building, which show how the marble plates are fastened – as if they were suspended from the top-, as well as show the material of the inner structure. It is as if the structure itself had protruding elements which hold to the cladding panel. Though the decorating elements of the exterior are strongly felt, as in other projects, such as in the famous Majolikahaus (Vienna, 1899), (Figures 7 and 08), in these buildings the graphic textile- influenced ornamenting is only present in the upper part of the building, exactly where we can see the metal fastening elements. The art-form is already directly related with the construction and the structural logic, thus anticipating the increasing expressive value of construction in Wagner’s later work (Figure 9).

Figures 4 a 6 – Karlplatz Station, Otto Wagner (1899). Figure 4 – Overview Historical photo.

Figures 5 and 6 – Details. R. Gargiani. Source: Fanelli, 1999: 119.

Figures 7 and 8 – Majolikahaus Building, Otto Wagner (1898). Figure 7- Overview. Historical photo. Source: Fanelli, 1999: 109. Figure 8 – Detail from the façade. Unknown author. Source: Leatherbarrow, 2007: 100. Figure 9 – Karlplatz Station, Otto Wagner (1899), detail. R. Gargiani. Source: Fanelli, 1999: 120. sumes a decisive symbolic importance.” (Fanelli, 1999: 74)

In the following years, Wagner explores many variations of this constructive detail and even starts to adapt this solution to other types of structures. “The first examples of marble plates anchored to brick and stone wall structures appear in the study sketches for the modern art gallery (Viena, 1899)” (Fanelli, 1999: 83). The fact that the fastening element of the cladding is metallic, and the structure is made of a different material makes their relation more ambiguous; it looks as if the construction prevails over the structure. Yet, there is no doubt that the symbolism that Wagner allocates to the façade through this detail is strongly related with tectonic logic.

Figure 10 – Church. Leopold Am Steinhof, Otto Wagner (1904), detail of the façade. Charles H. Tashima. Source: Leatherbarrow, 2007: 101. Figures 11 and 12 – Postal Savings Bank, Otto Wagner (1904-1906, 1910-1912). Figure 11 – Detail from the façade. Charles H. Tashima. (Leatherbarrow, 2007: 102). Figure 12 – Overview Unknown author. Source: Fanelli, 1999: cover.

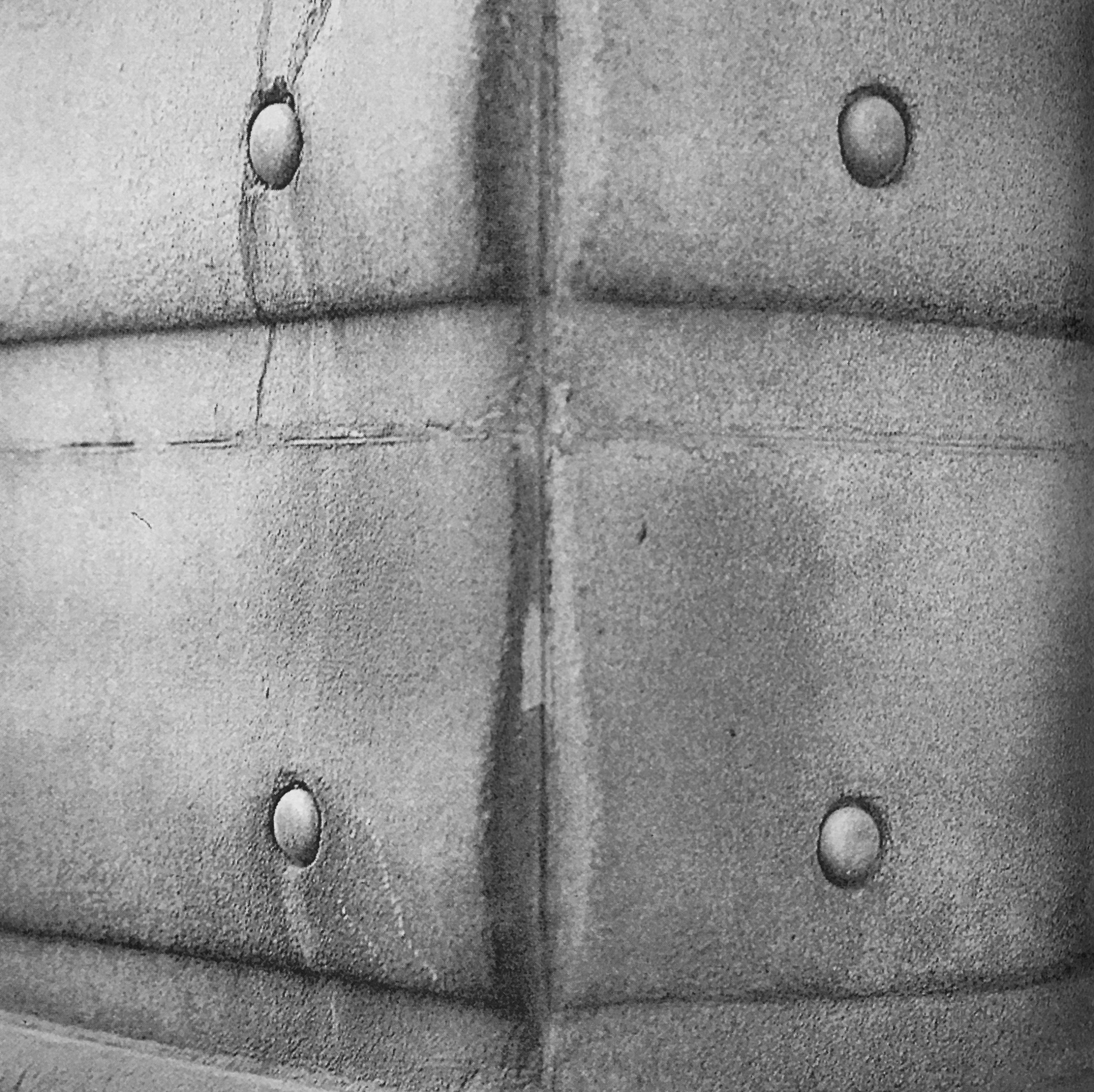

Wagner’s research reached its peak after 1903, in the two monumental buildings the architect developed for the city of Vienna at that time, the St Leopold Am Steinhof Church (Vienna, 1904) and the headquarters of the Postal Savings Bank (Figure 10), built at two different stages (Vienna,1904-1906 and 1910-1912), (Figures11 and 12). The latter is the most paradigmatic, not only because of the complex and hierarchic language that Wagner uses with this constructive solution, but also because it is a large-scale building opposite the Ringerstrasse axis, exactly where there are several buildings designed by Gottfried Semper, in particular the National Theatre, which Wagner had used critically to describe as an error (Wagner, 1993: 84). In this project, Wagner uses a heavy brick structure, yet applies metallic fastening to all claddings, whether stone or metal, and which he uses in the exterior and the interior of buildings (Figures 13, 14 and 15).

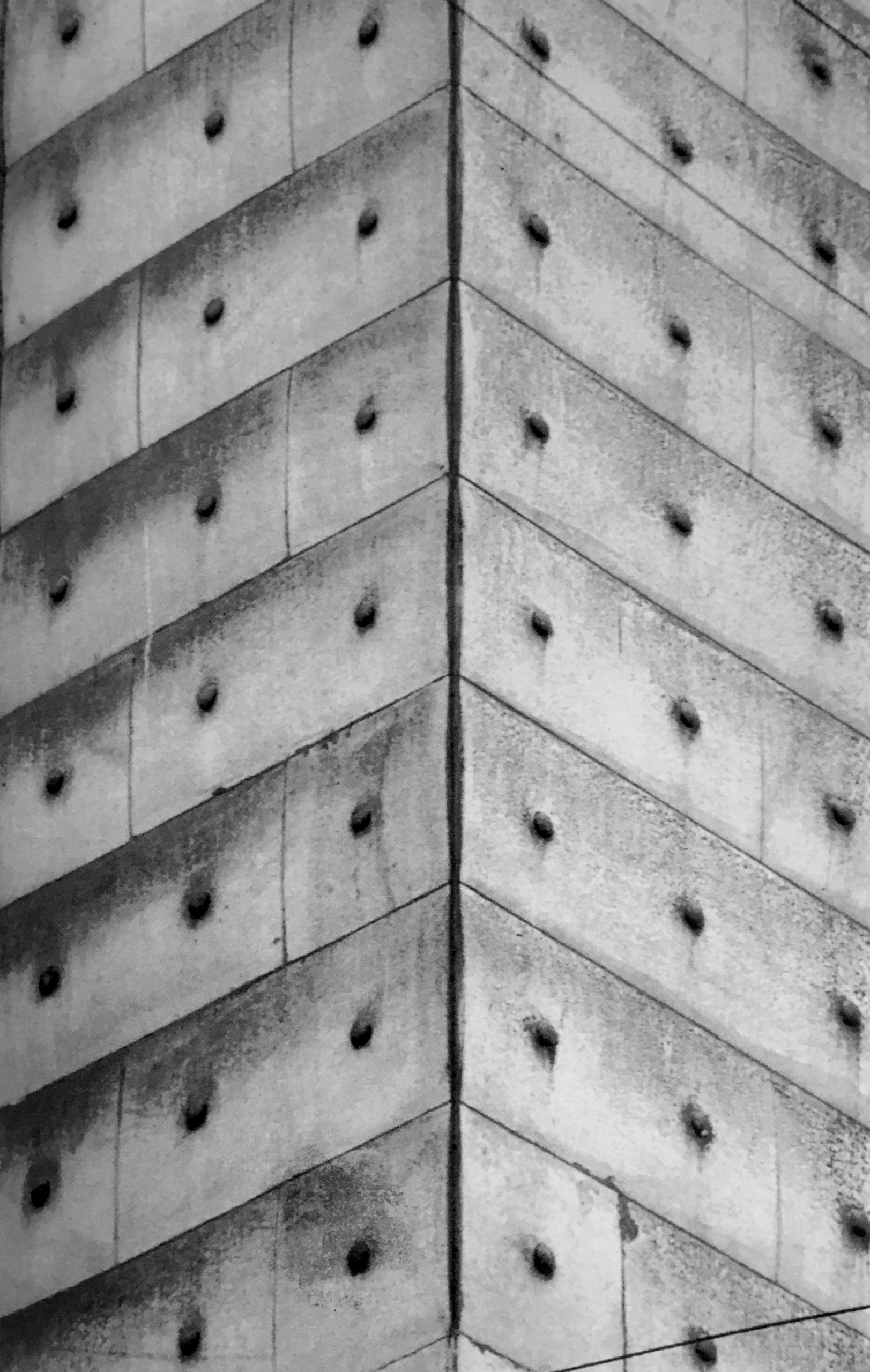

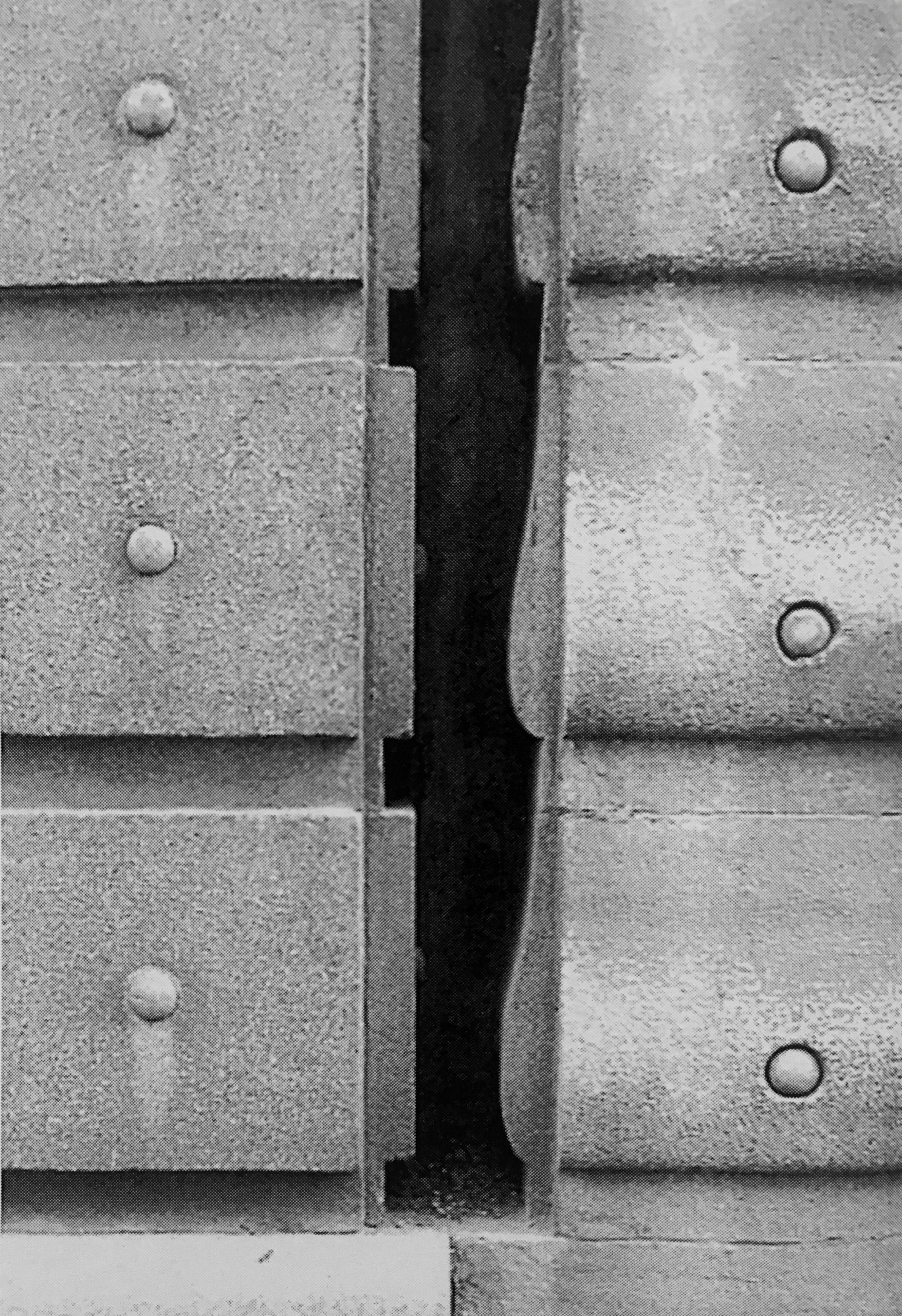

In terms of the exterior façade, like Hoffmann, Wagner also aims to celebrate how light and thin the exterior cladding is, which generically coincides with Semper’s reflections, though Wagner’s interpretation is very different. While Hoffmann works on this idea by hiding thickness, Wagner uses the corners to lean the cladding of both sides together and allow the actual thickness to be seen when the two meet:

“The stone basement is classical in style, but on the corners, we can see a certain modern lightness that exposes the artificiality of this gesture. This approach exposes and hides at the same time. It is a form of construction that distinguishes itself, resulting in an idealized or denaturalized art of construction.” (Leatherbarrow, 2007:103), (Figure 16).

Figure 16 – Postal Savings Bank, Otto Wagner (1904-1906, 1910-1912), detail from the exterior. R. Gargiani. (Fanelli, 1999: 134).

We can therefore understand that the foundations are made with 6- to 9-centimeter- thick granite plates while in the upper part of the building, 2-centimeter Ratchinges marble plates are used. This reinforces Wagner’s idea that by reducing the thickness of the exterior cladding a more noble material could be used (Figures 17 and 18). This hierarchical logic made visible in the exterior materials is also applicable to the fastening details. Wagner aims to add symbolic character to the main façade, whichis related with one of the city’s main streets, and states that “the marble plates are perforated in the center and fixed to the wall (…) In the central part of the façade, visible from Ringerstrasse, the slabs are decorated with plied aluminium” (Fanelli, 1999: 85).

Figures 17 to 19 – Postal Savings Bank, Otto Wagner (1904-1906, 1910-1912), details from the exterior. R. Gargiani. Source: Fanelli, 1999: 128, 131, and 128).

The joining of the exterior cladding repeats the detailing, in this case using iron rods, about 20cm long, fixed to the structural wall and perforating the wall to the exterior.

These elements are covered with lead in the first stretch and in the outer rim, a rivet similar to those used in the metallic structures on the inside of the building, here covered with dull aluminium (Figures 19 and 20). As Keneth Frampton states, Wagner’s clearly wants to convey the building’s constructive truth for its users:

“You meant to think that this metal stubs hold the stones into the fabric and that the metal pieces in the stone are essential to the cladding of the building. In fact, I think in the end technically they don’t add that much but it’s an expression of a desire on the part of Wagner that the structure, both in the big sense but also, coming down in scale, to the little balls, it’s all the same. The structure is what is uniting the whole building. .” (Frampton, 2020)

These elements are not responsible for fastening the building’s covering in a definitive way but are a key element in the construction process. It is as if Wagner wanted to leave the wood truss visible after building a brick structural arch. Wagner’s economic awareness was raised after the project for Vienna’s metro stations, and that was made evident in his management of materials and construction timelines. This constructive system allowed that the marble plates could be fastened faster since the metallic fixing ensured their final positioning while the mortars slowly dried (Fanelli, 1999: 85). The art- form is a direct consequence of constructive form and marks the symbolism of its production. Wagner is able to expand the concept of cosmic and rhythmic symbolism advocated by Semper and reconcile it with the structural and constructive logic of Karl Bötticher’s theories. According to Frampton,

“The Postsparkassenamt is a key building of Wagner’s career. So, in that sense we could say that Wagner is unhappy about the fact that Semper is preoccupied with ornament being a question of rhythm or cosmic writing because it is not deeply structural. Wagner wants the ornament to be deeply structural and that’s a very sensitive difference but it’s very important. ” (Frampton, 2020).

This constructive logic may be found in the whole building, including in the metallic structures and glass coverings in the main inner space. However, the most relevant here is precisely the fact that Wagner’s constructive detail, through its micro-scale, is responsible for the expressive and monumental features we see in the building. It is also through it that we identify, as we do in Wagner’s writings, an acknowledgment and a criticism to Gottfried Semper, the architect who most influenced Wagner’s career as an architect and as a scholar.

4. Conclusion

Otto Wagner’s key role in modern architecture is unquestionable. His advocating the rational use of new technologies, taking advantage of their expressive potential, has contributed to a break with an eclectic neoclassical architecture towards a new style he called modern. A few years earlier, Karl Bötticher had foreseen this scenario, when he stated that

“no one realized that the origin of all specific styles rests on the effect of a new structural principle derived from the material and that this alone makes the formation of new system of covering space and thereby brings forth a new world of art-forms” (Bötticher, 1852).

Wagner has shown that he was aware of this concept when he affirmed that art-forms should derive from construction, thus negating the idea of masking as hiding constructive reality, as ambiguously referred by Gottfried Semper (Wagner, 1993: 81). Masking is also present in Wagner and his close link and continuity in regard to Semper is unquestionable; yet, on this topic, the divergence is implied.

Both the Palais Stoclet, by Hoffmann, and the Postal Savings Bank, by Wagner, are heirs to Semper’s legacy. The difference between them lies in the details. They either hide or reveal the face behind the mask, the bone under the skin. Hoffmann uses art- form to hide, while Wagner uses it to reveal. In this sense, we could conclude that Hoffmann is closer to implementing Semper’s ideas. The constructive detail that Wagner develops over several years and applies in such a radical manner to all the elements of the Postal Savings Bank is an obvious evidence of that divergence. It is a subtle difference in interpretation that is significant and places the issue at an almost philosophical and ontological level. Where is architectural truth? What is the origin of tectonic forms?

In his text “Das Prinzip der Bekleidung” (The principle of cladding) architect Adolf Loos lists almost item by item Semper’s theories on textile art and the origin of architecture: “In the beginning was cladding”. Loos states clearly that an architect’s first task is to choose the cladding and only after that design the underlying structure. This perspective is completely the opposite of constructive and structural principles advocated by Laugier or Viollet-le-Duc, who idealized the structure of the primitive cabin as the foundation of architecture. The opposition between the core form of the heavy structure and art-form of symbolic revetment evokes the debate between Karl Bötticher and Gottfried Semper on the construction of Greek temples (Hermann, 1984:139).

In the fourth chapter of “Modern Arkitectur” Otto Wagner explicitly uses the concepts of core form and art-form described by Karl Bötticher in the book “Die Tektonik der hellenen” (the tectonics of the Ancient Greek) and presents a perspective that has obvious links with Bötticher’s. The fact that Wagner does not mention Bötticher’s name is rather curious and there is no objective reason for this though it may be explained by the disagreements with Semper on this exact topic. Bötticher claimed that architecture depended on two concepts: the core form, which would represent the mechanical structure, and the art-form, which would reveal the static function of the building through ornamentation. They should originate organically and simultaneously. A few years later, Semper would adapt Bötticher’s idea of art-form to his theory on cladding and give primacy to the symbolic act of clothing the building and associating that gesture to the origin of primitive painting and the cosmic presence of Humankind in the world.

We cannot state with absolute certainty that Wagner read Bötticher’s book, though he probably did during his brief visit to Berlin while he was studying (Mallgrave, 1988: 4). In any case, the divergence between Wagner and Semper’s thought is exactly what links Wagner and Bötticher. We could almost deduce that the research on the metallic detail to attach cladding is an attempt to conceptually reconcile them. Symbolic ornament derives from structural necessity and thus attributes cultural value to the act of building. Through this detail, Wagner clarifies the coordination between the “core form” and the “art-form”, two concepts that still hold huge potential as a tool to analyse and create architecture. Their coordination, interdependence, confrontation, or negation is present in buildings erected since the 20th century and the actual scope of its definition must be clearly explained.

Bibliography

BREITSCHMID, Markus – Can architectural art-form be designed out of construction? Virginia: Architecture edition, 2004. ISBN: 978-0-9702-8208-8

BÖTTICHER, Karl – The principles of the Hellenic and Germanic ways of building with regard to their application to our present way of building (1852). In Foged, Isak Worre; Hvejsel, Marie Frier – Reader. Tectonics in Architecture. Aalborg: Aalborg University Press, 2018. ISBN/ISSN: 978-87-7112-671-6

BÖTTICHER, Karl – Tectonics – Theory of Raiment. (1844) In Oechslin, Werner – Otto Wagner, Adolf Loos, and the road to Modern Architecture. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN: 978-0-521-62346-9

FANNELLI, Giovanni; GARGIANI, Roberto – El Principio del Revestimiento: Prolegómenos a una história de la arquitectura contemporánea. Madrid: Akal, 1999. ISBN: 84-460-1180-8

FRAMPTON, Kenneth – Interview given to João Quintela within the scope of PhD research. To be published (not accessible). Porto: 2020.

FRAMPTON, Kenneth – The Structure and Symbolism of the Art Nouveau 1851-1914. Tokyo: 1981. ISBN/ISSN:

FRAMPTON, Kenneth – Studies in Tectonic Culture: The Poetics of Construction in Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Architecture. Cambridge: MA: MIT Press, 1995. ISBN: 84-460-1187-5

FRAMPTON, Kenneth – História Crítica de la Arquitectura Moderna. Barelona: Gustavo Gili, 2009. ISBN: 9788425216282

HERRMANN, Wolfgang – Gottfried Semper: In search of Architecture. USA: The MIT Press, 1984. ISBN: 0-262-08144-X

LEATHERBARROW, David; MOSTAFAVI, Mohsen – La superficie de la Arquitectura. Madrid: Ediciones Akal, 2007. ISBN: 978-84-460-2312-8

LOOS, Adolf – Dicho en el vacío (1897-1900). Valencia: Colégio Oficial de Aparejadores y Arquitectos Técnicos de Murcia, 2003. ISBN: 84-505-0132-6

LOOS, Adolf – Ornamento e Crime. Lisboa: Edições Cotovia, 2004. ISBN: MALLGRAVE, Harry Francis – Modern Architecture, Otto Wagner: A guidebook for his students to this field of art. Santa Monica: The Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities, 1988. ISBN/ISSN: 0226869385 https://www.getty.edu/publications/resources/virtuallibrary/0226869393.pdf

MALLGRAVE, Harry Francis – Otto Wagner: Reflections on the Raiment of Modernity. Santa Monica: The Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities, 1993. ISBN/ISSN: 0-89236-258-8

OECHSLIN, Werner – Otto Wagner. Reflections on the Raiment of Modernity. Canada: Getty Publications, 1993. – The Evolutionary Way to Modern Architecture: The Paradigm of Stilhülse un Kern. ISBN:

OECHSLIN, Werner – Otto Wagner, Adolf Loos, and the road to Modern architecture. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN: 978-0-521-62346-9

SEKLER, Eduard – Structure in Art and Science. New York: George Braziller, 1965. – Structure, Construction & Tectonics. ISBN:

SEKLER, Eduard – Essays in the History of Architecture presented to Rudolf Wittkower. London: Phaidon, 1967. – The Stoclet House by Josef Hoffmann. ISBN:

SEMPER,Gottfried – The Four Elements of Architecture and Other Writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. ISBN:

SEMPER, Gotfried – Escritos fundamentales in ARMESTO António – Escritos Fundamentales de Gottfried Semper. Barcelona: Fundación Arquia, 2014. ISBN/ISSN: 978-84-940343-2-9

WAGNER, Otto – La Arquitectura de nuestro tiempo. Madrid: El Croquis Editorial, 1993. ISBN: 84-88386-02-8