Ricardo Carvalho

rcarvalho@autonoma.pt

Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa (CEACT/UAL), Portugal

João Quintela

joaopedroquintela@gmail.com

Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitecura – Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, CEACT/UAL – Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa | Professor no Da/UAL | Arquiteto, Portugal

To cite this paper: CARVALHO, Ricardo; QUINTELA, João – Interview to sculptor and lecturer Carlos Nogueira. Estudo Prévio 19. Lisboa: CEACT/UAL – Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa, 2021, p. 2-17. ISSN: 2182- 4339 [Available at: www.estudoprevio.net]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.26619/2182-4339/19.2

We, João Quintela and I, Ricardo Carvalho, are really pleased to welcome you for an interview, in the studio of Universidade Autónoma. I think we must introduce you as the great artist that you are, as well as a lecturer and an educator, since that is also a large part of your life and has much to do with architecture and the work we do here, in the Architecture Department at Autónoma. I would like to welcome you and thank you for accepting our invitation to spend the next hour talking about Art, Architecture and about how you share your vision of the World with others.

First of all, I would like to compliment Ricardo Carvalho and João Quintela for who they are as people, as professionals and as friends. It is my pleasure to be here.

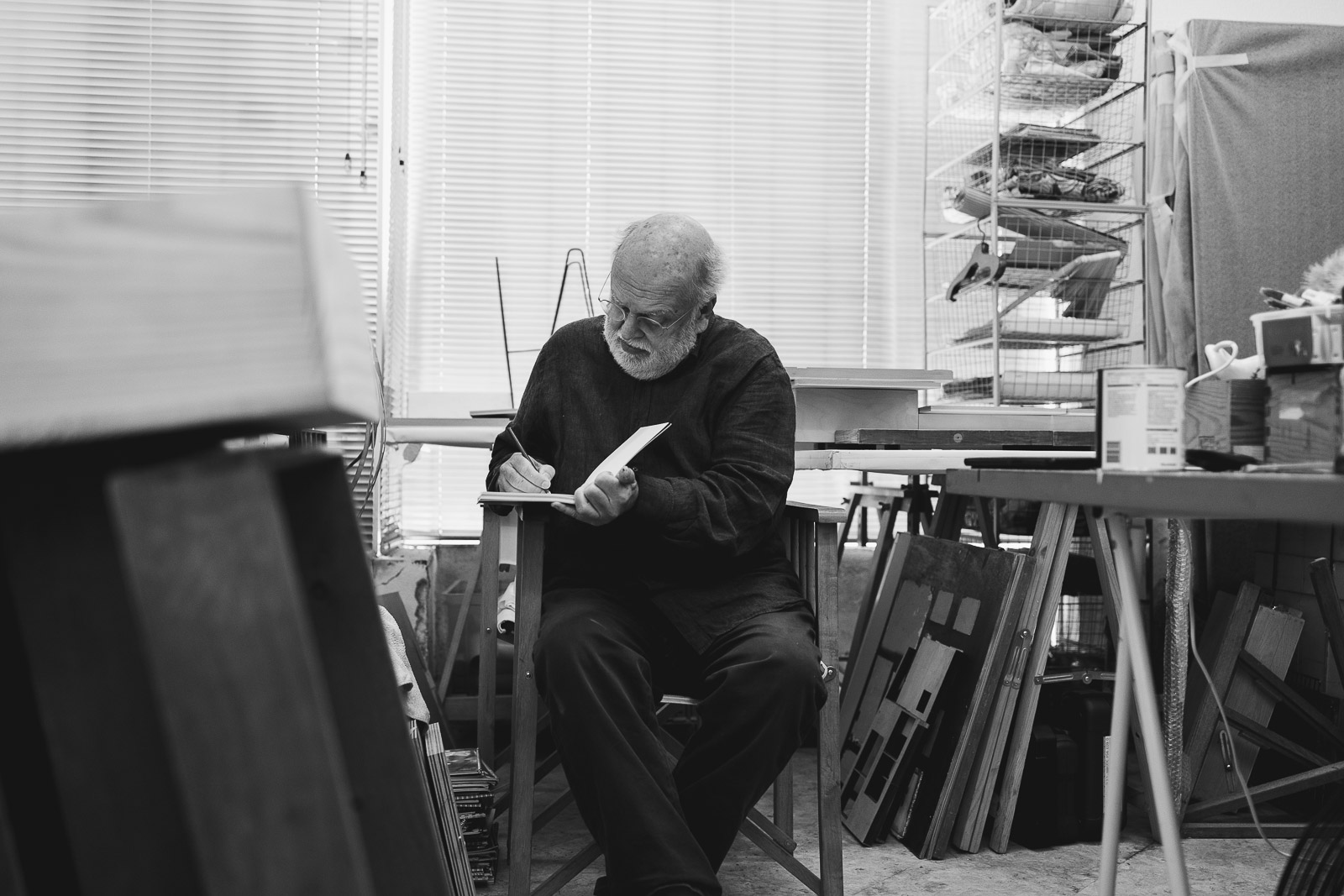

©Gonçalo Henriques + Estudo Prévio

I would like to start by talking about your artistic production. One of your pieces started as performance, in which you included writing a sentence on a wall that said “Todo o mundo é composto de mudança” (all the world is made of change). I like this sentence from the point of view of politics, art, architecture, love and also pedagogy. Do you agree with this view of the world as endless variation of itself? And what about the idea of sharing it with students?

I will start by talking about the performance itself, so that those who are not familiar with the work may have an idea of its range. I showed this at 2.a Bienal de Cerveira, whose theme was “Camões” because we were then celebrating the 400th anniversary of the poet’s death. I was at the start of my career, not in terms of doing things, but in terms of showing things. I designed an installation, which was also a performance, that consisted of a huge white wall. I had requested a wall that had already been used, one with time, history, life and I was given a long wall with a panel. I asked that there would be another panel to provide continuity to the first one. Creating this piece was very challenging. I left Porto and got on a train that stopped at every station. I eventually fell asleep and, when I woke up, I saw the bag where I had all the materials for the piece outside the train. I jumped off the train and then got back inside with the bag while the train was already moving. In a second, all my plans could have been changed.

I started by spray painting on the wall the sentence “Todo o mundo é composto de mudança” (all the world is made of change) a verse from one of Camões well-known sonnets. I had gone to the National Library and had had access to the oldest known original of that sonnet. I designed thousands of pamphlets with that verse in very big letters. At the bottom part of the pamphlet, I wrote my name and the place where the installation would be. At the top, I wrote by hand “A Ti” (to you) using a very old pen belonging to my grandfather. At the same time, I made four hundred little flower bouquets with paper napkins (they were given to me by the owner of the café I went to every day, I asked him to sell the napkins to me but he ended up offering them to me) around which I placed a red cotton ribbon, at the tip of which there was a rectangular paper label. On the label I wrote “A Camões” (to Camões) by hand, and, below that, my name and Bienal de Cerveira, etc.

Initially, I wrote “Todo o mundo é composto de mudança” but not in just any way. For example, on one corner I write “MU” (the beginning of the word “mudança” – change) and as we turned the corner, I wrote “Dança” (the end of the word which also means “dance”). Among other scribbles, I spray painted the pronoun “Te” (to you, you). The relationship with the “other” which I emphasized by circling the pronoun.

At the opening, in the space between the two walls, which formed a right angle, I spread the pamphlets on the floor, as if they had been dropped without much thought, and i also placed a large amount of the flower bouquets on the floor. The flower bouquets had the label “A Camões” (to Camões). On the wall there were about six or seven pages that described the project. With the material protected and hidden and the help of the assistants, who handed them to me as I walked the space and in the village of Cerveira, I laid down the flower bouquets on the floor, in honour of each of the four hundred years since the death of Camões. I also gave people the leaflet where you could read “A Ti. (To you) Todo o mundo é composto de mudança”. (The world is made up of change).

I am also a teacher, I have been a teacher all my life, and I love that. And I must say that teaching, as everything else in my life, is a mix of things. In my life, everything is a mix of things. Moreover, people reconnect even if they have not seen each other for years. And your feelings, your thoughts, are always exchanged with those you are okay with. And I have been lucky to have been okay with many people.

I always start my classes by telling students that I will consider them people first and only students second. As people, I want them to understand that the world is made up of change. This means that even those who did not have great grades at school – and there are many students like that – I feel I have to invest in them, and I know that, even though it is not as common as I would like, they can become great students now. Therefore, I ask students to strive to learn, that they like what they are doing and that they continue to work. I ask them to create a method, an approach, a perspective, a skill to acquire information and knowledge that they will use to become whatever they want, to attain their goals.

I had a student in the 1st year of Architecture that is a clear example of this. I had just given students the bibliography as for that semester when one student claimed he had never read a book. I was surprised, of course, though I tried not to show it. and simply told him it was time he started reading. He should start with a book that met his needs and interests. I will simply say that I saw him with a book throughout the years he was at university. I have not seen him for a long time, but I know that he is doing his PhD. A student that enters university without ever reading a book and then does his master’s and starts a PhD means something. This does not happen with every student, but it did happen with one student and that is a positive thing. Therefore, what I want from my students, and when I talk about art or this piece in particular, what I urge students to do is to learn how to learn.

©Gonçalo Henriques + Estudo Prévio

I find these different readings very interesting, and I believe these ideas extend to your classes on Drawing. I was fortunate to have been your student in high school and then at university and one of the things that I remember is the fact that your classes were very practical, complemented with poetry reading, with classes on music and other thoughts on life or even more philosophical, which evidences an understanding of Drawing that is wider in scope. So, I must ask you: What is Drawing for you?

Drawing is much more than a course; it is a Universe. And the Universe encompasses everything. I must say that I was very lucky to have been lived in Africa, even though there was war, and having taught at a religious school where the children where poor but who knew their land and their environment. When they started to work with their pencils and papers and started drawing, it was fantastic, I have kept many of those drawings.

In class, I show films, I recommend some films, or I take students to the ballet. For any years, I went to Gulbenkian with three groups of students to watch the general rehearsals. I would take them and them discuss what we had seen. Each student and I would take their notes to class and discussed what we had seen and what we had understood of it. Because the universe we were talking about was far wider and richer than the music or the dancing that we had seen

Speaking of dancing, I have to say that I have always taken my Architecture students to watch dancing. And, of course, I have not taken them to see classical ballet. Classical ballet is important in historical terms, but I prefer contemporary ballet because it requires more in terms of creation, invention, and participation. I take them to see ballet because my understanding of space, I know that for sure, derives from the place where I was born, which was very far from here and where the wind blows in a different way. It was an immense space of sky, sea, green and earth. I have often taken my students to see ballet because an architect is a professional who knows space as none other. And I think that there is only one other profession in which space is worked and there is self- knowledge and mastery of space and that is precisely dance.

I remember seeing Rudolf Nureyev enter the stage in Le Corsaire by Drigo, doing back pirouettes and dancing around the stage without losing the sense of geometry. Architects must master that knowledge and I would take my students to see ballet so that they understood what they needed to achieve. This is not the end goal because there is always more to learn.

I think everything has to do with everything. And in the case of Architecture, it is key that you know about all matters. For example, we all know that placing a wooden wall against a cement wall requires specific procedure. Though it is easy to do, it is hard to maintain it stable and resistant. I used to tell students to “look up as you are walking on the street. When you see this type of wall, try to understand how it has been built”. Architect do know a lot, but in some situations qualified workers, whose knowledge comes from experience, will be able or will devise solutions for those issues. Everything has to do with everything. I would have my students listen to opera because, when they listened, in particular when they listened to Maria Callas singing some arias, they would hear the nuances, the variations, the differences in intensity produced by each sound sequence and would realize that the city or the space they lived in is full of variations, is filled with links. And these links should be found, even if there is difference or error. I do not reject error but rather try to integrate it in the system.

©Gonçalo Henriques + Estudo Prévio

Your body of work evidences your particular approach to your pieces. You mention error often, you say that things are ongoing up to the moment you decide to sign a piece and it is ready to be shown to the world. This means that a piece is made to be public, but, before it is public, it belongs to the artist, it is private, and as a private piece it is in constant change. I would like you to speak about this and your perspective regarding an artistic piece being in constant change.

My work is developed very slowly. When I opened the Santo Tirso Museum, which was designed by Eduardo Souto Moura and Álvaro Siza Vieira, I used a bronze piece that was in my workshop and had been ready for 30 years. I thought that was the right moment to show it because it had aged with time. It has no coating because I don’t like that kind of finishing. Once, Fernando Calhau, who is one of my closest friends, told me: “Carlos, your pieces are all very well made. Why do you need to add that finishing?” I answered that “my pieces are made with the skills that I have”. I need to have a long relationship with my pieces before they can leave my workshop. And I only sign them when they leave it. When my pieces leave my workshop, they have already got some wrinkles. And time was what was lacking to their irreversibility.

I am getting older, but I do not feel old because of my wrinkles or because I cannot do what I want or because I don’t have any projects. I do sometimes feel old because I am no longer strong enough to pick up an iron bar and have to ask my assistant for help. Or because I cannot run up or down a ladder because my knee no longer works. In any case, things are in continuous change.

©Gonçalo Henriques + Estudo Prévio

I would like to ask a question related with the first part of the interview – when you talked about performative action – and with this issue of materials and time I would like to talk about what I consider a very relevant aspect which is the fact that you usually divide your work into two different moments. You call the first moment Wasting and Sharing – which includes performative actions and more ephemeral pieces – and you call the second Restraint and Permanence – which includes the pieces you are best known for because they are more permanent pieces which establish a dialogue with architecture. Can you tell us a bit about this very clear distinction and the relations you find between the two?

I had a wonderful childhood, in a wonderful land, where, on returning home after playing, my mother would only let me in after washing with the garden hose, because I was covered in dirt and sweat. I climbed up trees and fell from trees… I just want you to realize how rich my childhood was. When I was seventeen, I came to Porto to study and during those years and a few years later, life was a wonderful thing.

One of my goals was to reach other people somehow, even if it was to make them stop in order to better understand something. I gave things, lost things, posted things, such as flutes that I made myself using a basic method to learn the flute – all this because I believe that music is one of the ways to save the world. I wanted people to use those flutes and had music closer to them. Mine was an extremely happy world but filled with inconsistency. And then, at a certain point in time, I also gained, for good and for bad, a sense of the finite. And because my work mostly disappeared and I had very little documentation on it (fortunately, I have collected more than I had hoped and I always had a written plan), I started to work with more durable materials. And, if initially I focused on giving, wasting, sharing, though, in some situations, anonymously, in the second moment I pretentiously started to work with the “best materials in the world.”

It is obvious that Corten steel is not as durable as all that but Liquitex paint (though it was not sold here) is. I ordered the paint from the USA in 1000ml or 5000ml bottles. And I tested and tested these paints by painting a big sheet in a certain colour, ripping the sheet in half and placing one half inside a drawer and exposing the other to the sun for one year, and the paint’s resistance to light was proven. So, I started wanting to make things that lasted. And a word emerges. Eternity. I like this idea of Eternity. When I think about the Cosmos, and I really like science, I think of a place you cannot reach. What is that eternity? I came up with a formula to solve that extension “beyond the very edge of the world”. While there is land – up to there. So, I started making pieces that lasted, that were consistent, that were described in order to be restored and replaced, if that is the case. Many of those projects I am now placing in acid free storage boxes. Why? So that they can last at least a bit more.

This brings to mind the fact that your work is part of a wide field of research that includes many artists from different parts of the world, many of whom equally wonderful artists, such as Donald Judd, Carl Andre, Robert Smithson, just to name a few of the best known. I believe that both you and a part of these artists have understood that the heritage of architecture may become sculpture. This is why your work is sometimes walked on, is viewed as a wall in the garden, as a stacking of a certain material, which may be either hydraulic mosaic or brick. Sometimes its composition is similar to an archetype, similar to a house, and sometimes it is directly related with its architectural culture, in its more scholarly perspective. I would like you to talk about this in regards to a piece you made for The Economist Plaza – a work by Alison and Peter Smithson in London – which is at the heart of a reference piece from post-war culture by two famous architects, as well as about the fact that your work is, truly, a tribute to the place that receives it.

© José Manuel Fernandes (beyond the very edge of the earth, The Economist Plaza, 1998)

Exactly. I must say that there is one place in the world that I like and that is home. I really like my house. I have been living there since 1970, it has already undergone some changes, I have designed the interior, the stairs, the raisers, everything. For me, home is life’s jewellery case, life’s box, in the words of Le Corbusier. Since home is so important to me, I see it as a place for life or the place to preserve life.

This piece, which is called beyond the very edge of the earth, in Portuguese até ao fim das terras todas, came about after I was invited to participate in the Triennale Milano. I was not invited because I was an architect, but because, according to the rules of the Triennale then, each group of architects took professionals from other artistic fields – that year Australia took painting and Egypt took poetry. The commissary invited me to take sculpture. The Portuguese group included good architects and, once the Triennale was over, someone had the idea of disseminating that exhibition. It was shown in the USA and in other places… And my sculpture was also shown. When the exhibition was going to be held in London, they invited me to create a piece for that particular place. And that

was a place where there was an architecture institution. I could make my piece in that area, wherever I wanted.

I must say that I was really well treated there, unlike what sometimes happens, namely in Portugal or in Brazil. But not there. When I arrived for my first talk with them, after my work was designed, I was told to be at the institution at 2 p.m., I saw six men enter, each at a time, and, when they left, they were all wearing red overalls. One of the men was the light engineer, the other was the structure engineer, each man was an expert in his field, and they were there to understand the weight of the piece, the technical requirements for the light, etc. When the piece was being assembled, I had a construction engineer and four senior Fine Arts students, I picked up a hydraulic mosaic tile and the assembly architect told me I could not touch anything because if the tile broke, the insurance would not pay for it.

Just as in all my pieces, I started by engaging with the space. What does that mean? It’s to try and understand the space. It’s to know its temperature, its colour, its light, the wind, understand who walks past it and how they walk past it – in The Economist there is a large stone bench where people sit during lunch time – I aways engage with my spaces for a long, long time. And I must say that the spaces often tell me what to do. I had the opportunity to make this piece because they were very demanding, they wanted a piece specifically designed for that place. They gave me the opportunity to understand what I consciously wanted to do. Because art is sweating, working, much more than inspiration.

I measured, I photographed, I identified relations. I can tell you that my piece, which was two parallel walls at an L shape, one wall very narrow and the other very wide, was placed so that all its limits coordinated with what existed before. One side was the continuation of the bench of that garden, two of the other sides were in line with the building’s central body. Another arm pointed to some stairs that gave access to the street, but it pointed precisely to the central axis of the stairs. I built something that, whether evidently or not, already had to do with the place. And that is always key for me. It is almost as being in the wind, a very strong wind. You cannot fight the wind. You have to run from the wind or cup your hand so that the wind hits and then deviates from you. You cannot force it. Things must be natural somehow.

Sometime later, my friend Luís Tinoco sent me a cultural page from The Independent, where there was a huge photo of my piece, bigger than A4 size, and the article was called Curadores de Curadores. The most respected curator at the time chose me to photograph herself with my piece. At the time, the organization told me we needed to invite Michael Archer – who is a professor at Goldsmiths College, and a very relevant critic. A month later, I got a letter by Michael Archer who simply said he had gone to Brighton University, where the piece is now, and apologized for not having seen it atThe Economist but had really liked it and wanted to follow my work. That is gratifying. More gratifying even is the fact that he writes to me every now and again. Even more gratifying was that, a few years ago, when I went to London, I wrote him asking him for lunch and got an answer stating that he declined lunch, that i would be staying at his house.

© António Jorge Silva (casa comprida com árvore dentro, Santo Tirso, 2012)

I believe, then, that your pieces aim to belong to the places they are in – that is a feature of your work. This means that topics, such as tension, rupture, impertinence are not features of your work. Your pieces clearly work through belonging, empathy, continuity. The piece in The Economist is an example of this. But even when you work in a non-urban environment and you have pieces in permanent exhibition here in Portugal, those pieces also want to belong. They often grab a tree, create the place. Do you agree?

I do. And I must say that this occurs because I go to the park, in the case of Santo Tirso, for two or three days and take photos and photos of the place and search and search for the place. Of course, I wanted a place where there would be space, but I wanted to find a place that had something special. And then I found two trees, very close to one another, and I said to myself: “I want these trees to converse beyond the wall that I will place between them” – and the roots and the leaves did, in fact, converse… Curiously, Alberto Campo Baeza, who is someone who follows my work closely, wrote an article for the catalogue of that exhibition in which he used a different story and found a solution for that marriage, which I really appreciated reading and acknowledging, i.e., it means that things have not stayed the same, they can move in a different way, but they never stop moving.

© António Jorge Silva (chão de cal, Cordoaria Nacional, 2018)

Within this dialog with architecture, the constant attempt to decrease the borders between fields is rather clear. Your texts are poetry, performative actions are dances, drawings are sculpture, sculpture is architecture. And the specific case of architecture seems to me very relevant because, in a sense, it subverts elements that are obviously architectural, allocating them new uses and new features: the doors, a vertical element, which you include in sculptures as horizontal plans. he hydraulic mosaic, which is used to pave floors, which you layer, exposing the tiles’ sides. Even lime, which is usually used on walls, you use to cover the whole floor of a room. Could you tell us a bit about your will to dialog with the different fields and how that is linked to appropriation and redesigning of materials outside their usual context?

What I feel like saying is that I love Architecture. I think I love architecture more than some architects. On the first day I attended primary school, in that afternoon I was at a neighbour’s house whose children were my friends and she asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up. I answered that I wanted to be an architect. At twelve years old, I had designed houses and museums. It just happened that, to shorten my way to architecture, I studied art. I studied sculpture in Porto and then studied painting in Lisbon. And I must say that I found out that I could not be an architect, because I would not be able to deal with confrontation and it is not always easy to deal with builders or with owners who often choose the less adequate solutions and do not accept the good solutions offered by the architects.

Each and every material has its own features, and they are as many as we can discover or invest in. And I like materials. In my workshop, I have samples of stone, tin, glass, of all that stuff. I even have kitchen tools; though I don’t turn my workshop into a kitchen and not use pans as pans, they are elements that recall shapes, links between surfaces, which I find very interesting. My work is that of recycling, a person that discovers materials and guesses their qualities and reworks them. I am always trying to link everything. I also mingle with very young and very old people. Each has their own truth, related with their age and time, but I have friends of all ages, not only people from my generation who think like me. Luckily, I have friends who think the opposite of me, but we respect each other and enjoy the best the other has to offer. Because, if they are my friends, we both want the best, we just do not choose the same path to get there. It is the same thing with materials. Materials are not rivals of other materials. What you need is to know how to connect them. Art Nouveau gave us beautiful examples of this: an iron ring with a stone, or a piece of glass with a rim made of gold.

It is as if you were saying that everything can be more than ordinary. Art does the opposite, i.e., it is the way we look at things that transforms them, that changes them. And materials, in your work process, seem to be subject to that appreciation, to that enchantment. On the other hand, materials gain an order that they sometimes did not have, because, due to repetition, to stacking, to the idea of construction…

They gain a density and a weight that becomes visible and recognizable.

I agree. And your work, when it is finally made public, when it is in a museum or in a landscape, it still takes on an idea of stability and order. You have already mentioned permanence and eternity, but I think that, before that, there is an idea of the order of materials. The materials are ordered, they are not in conflict…

They are in their own condition. You just have to find it.

What about life?

Life? That is a wonderful thing. I love life. I am old, I am 73, I have many projects and, in order not to waste any time, there are things that I have had made at a metal workshop. So that I can use them in three or four years. I love life, I love having been born, I love the people I know, I love my people, my friends. I have more friends than most of my friends. I have a very rich life because I have many friends to my heart’s content, as Plato said though with a slightly different meaning…

The body is getting old in some respects, but there is always an assistant whose arms are stronger than mine, who helps me make things, or a friend who helps me take things or who takes me to a place or other – and I am thinking about João (Quintela), who is friend for life. Or Fred, who is my assistant at the workshop. Life is a wonderful thing. And you have to enjoy it.

My provocation is the result of having remembered the interviews Pierre Cabanne made to Marcel Duchamp, in the 1960s, Duchamp would have been around your age, and Pierre Cabanne asked him: what has your life been like, Marcel Duchamp? And he answered in a very disconcerting way, saying: “My life was that of a café boy. What I really enjoyed doing was to sit by the window in the café and watch the women walk by.”

I did not know that. I did not know that, but my life is a very good life.

And you don’t separate art and life? Your work is also your life?

No, my work is my life. They are the same. I have a house that I think is organized but there are moments when I have to walk on the tips of my toes because the floor is covered with ongoing work.

And do you still wear a shirt?

I do. Do you know what? One of my pieces was rejected by Sociedade Nacional de Belas Artes, in which I wanted to recall the shirts I used at the time… It was a different time, different mentality, in my application to the exhibition, I had drawn a long and strong line on the floor and had two shirts lay on top of the line, which meant they had been undressed and that that line had been crossed…

© António Jorge Silva (junto ao chão, capela do rato, 2018)

I thought the way you talked about life rather curious. Some people say that your work almost evokes death. I was thinking about your intervention in Rato Chapel, which has a very strong symbolic dimension and almost opposite to what you have just stated. We feel the silence, the twilight, all the dark elements, and we just have the salt with defined light.

That surface with salt can be a tomb or a table for a meal. I am deeply aware of death, and I think about death every day. It is inevitable, it will happen, but, until then, I want to enjoy life to the fullest, right to its core.

I have a great idea, which we can discuss, and it has to do with a very strong piece that you created, in which you offered people pencils to paint gray days. We need those pencils more than ever, because the world seems to be readjusting in a very frightening way… What pencils would those be?

In that performance, I sent those pencils to one hundred people who I randomly found in the phone book. Therefore, one hundred people will have received envelopes with colour pencils, unbranded, as well as a sheet of paper with the sentence “Pencils to paint grey days”. Those pencils were sent on the eve of winter so that people could get ready for the cold typical of the season.

Today’s pencils are much more complicated. They demand time for people to think about themselves, to say the least. I think there is no such time. As a teacher, I think parents need that time to be with their children, not just have the time to be with the children when they go to bed. Parents who had time to deal with the struggles of everyday life because those struggles show children how to deal with them and that will allow them to fly later on. I think people should have more time and, especially, should be able to identify those values that they feel would the best for them, The value of kindness, the value of cooperation, of companionship, the value of a good conversation, even without a fireplace. That is what is most important. People have to be more aware of themselves… I do not know what happiness is, just as I do not know what unhappiness is, I do not use those words. I know a great poet who has a book with a title that has to do with happiness. I would never call something “happiness”. Living your best life has to do with being able to know yourself better, giving yourself some time, yourself and those close to you. This does not mean that each one of us can change the world, I don’t believe that anymore, but if we can change two or three people close to us, that is already worth it.

João and I have a poem here, a part of a poem in honour of your performative side as an artist, as a person, since you read poetry to your students and to your friends. This poetry has obviously to do with an attempt to change the world because you are faced with ideas that make us think more, think again. They are two sentences written by Arseni Tarkovski. The idea is deep, the poem is very short: “No harm is lost, no good has been in vain”.

That is true, very true.

Thank you, Carlos!

https://carlosnogueira.com/