Rodrigo Lino Gaspar

rodrigolinogaspar@gmail.com

Arquiteto, Doutorando no Departamento de Arquitectura da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa (DA/UAL), Portugal

To cite this review: GASPAR, Rodrigo Lino – Chelas Urbanization Plan. Estudo Prévio 20. Lisbon: CEACT/UAL-Center for Studies of Architecture, City and Territory of the Autonomous University of Lisbon, 2021, p. 118-128. ISSN: 2182-4339 [Available in: www.estudoprevio.net]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.26619/2182-4339/20.01

Review received on 29 May 2022 and accepted for publication on 9 June 2022.

Creative Commons, license CC BY-4.0: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Chelas Urbanization Plan

|

Chelas Urbanization Plan emerges as the largest urbanization plan of the City Council of Lisbon (510ha), in the expansion strategy of the city, following the large-scale planning of Alvalade, Olivais Norte (40ha), and Olivais Sul (186ha). Its limits are well defined by Avenida Marechal Gomes da Costa to the north, Avenida Infante D. Henrique, and the railway line to the east, the railway line of Cintura Interna, to the |

|

south, and the escarpment along Avenida Gago Coutinho, to the west. Chelas has remained over time as a territory of very low occupation due to its natural conditions; it is one of the most topographically rugged areas in the city. The central N- S orientation valley and its secondary valleys correspond to watersheds that lead to large water lines of the city’s geomorphic system. This area of the city, in the 1960s, was occupied by vast agricultural land, organized around convents and farms, areas of cultivation and leisure, while the eastern riverside, served by river and the railway line, would give way to industry, attracting new population to work in the factories. |

The saturation of the consolidated city, soil availability, housing capacity and existing equipment agencies heralded the need for Lisbon to grow. The expansion of the city to the east, provided for in the De Gröer Plan (1948)[1], was divided into two parts, an industrial zone to the east and a low-density housing area, separated by a green one. The Office of Urbanism Studies (GEU) of the Lisbon City Council, between 1954 and 1958, elaborated an amendment to the plan in the eastern area: industrial areas were reduced, the housing area would be increased with higher densities, an equipment center and a green park was created in the airport servitude area.

Figura 1 – Aerial View of the East Zone of Chelas. Source: Revista Arquitectura, jan/fev. 1967, p. 7.

The GEU survey in 1955 revealed a population of 2,801 families living in Chelas, along with a predominance of industrial activities (Matinha Gas Plant, Petrochemical Sacor, National Soap Society, among some) that contributed to the exaggerated production of noise, smells, smoke, and dust. It was concluded that it was necessary to “safeguard the health of the area through adequate planning“. [2]

On August 18, 1959, it is published the Decree-Law that defines the “indispensable conditions for the orderly expansion of the city” (DL 42 454), with the aim of promoting housing, the main problem of Lisbon in the 1950s. To this end, it was created the Technical Housing Office (GTH), which was responsible for establishing the strategy of the programmes and the design of the dwellings. The 737ha of the eastern zone attributed to the GTH, were divided into two large zones, Olivais and Chelas, the first being subdivided into Olivais Norte and Olivais Sul.

Figura 2 – Slum neighborhood in Lisbon. Author: Fernando Mariano Cardeira. Available in: https://www.vortexmag.net/

Preliminary studies

A set of surveys and preparatory studies were carried out for the preparation of Chelas Urbanization Plan. The “Housing survey of slums and shacks existing in the administrative area of Lisbon” elaborated by GTH, coordinated by architect João Reis Machado in 1960, surveyed 711 units where approximately 806 families lived, 3034 inhabitants, in poor conditions and concluded the need to relocate them.

Data indicated that 50% of the population surveyed lived in the Chelas area in 1955; most of the young population, 47%, comprised ages between 0 and 14 years; 44% was unliterate; 48% of household heads worked in construction and industry; and, finally, specific data on the conditions of the precarious buildings indicated that 1% had a kitchen and toilet; 38% a kitchen, but no toilet; 61% without kitchen or toilet. Overall, 30% of the population of Marvila lived in these precarious buildings back then.

The “Study of occupation of the hillside in the city of Lisbon”, carried out by the architects Alves Mendes and Silva Dias, analyzed case studies for the design of Chelas Plan. Alfama is an example of high population density and spontaneous adaptation to topographic conditions; the main roads, looking for smaller lines pending, limit large areas crossed by ladders and alleys: the automobile system is independent and intersected by the pedestrian system.

Other studies carried on heritage identified the portal and galley of Convent of Chelas, classified as National Monuments[3], and unclassified buildings, the Palace of Quinta do Marquês de Abrantes, Quinta da Bela Vista, and Quinta das Salgadas. Regarding the system of Azinhagas that served the rural context, it was considered unsuitable for the needs of the height. The extensive areas of horticultural and arboreal culture were, in plan, intended to be maintained and cultivated by future inhabitants and, in some cases, could become public parks.

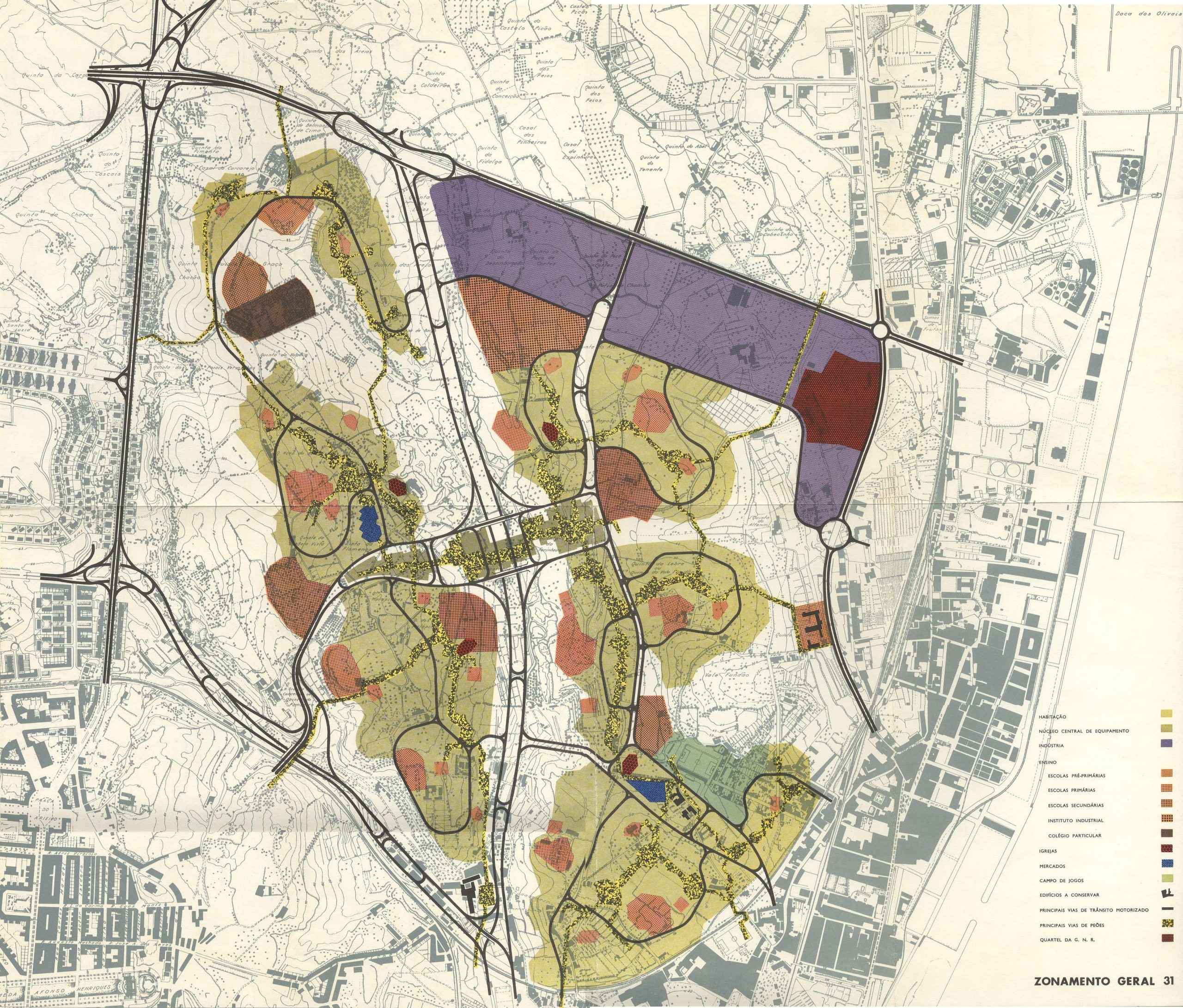

Figura 3 – General Zoning of Chelas Urbanization Plan. Source: GTH – Technical Housing Office of the Lisbon City Council, Chelas Urbanization Plan. Lisbon: Lisbon City Council, 1965, p.31.

Figura 3 – General Zoning of Chelas Urbanization Plan. Source: GTH – Technical Housing Office of the Lisbon City Council, Chelas Urbanization Plan. Lisbon: Lisbon City Council, 1965, p.31.

Base Plan

The team of GTH, organized by architect José Rafael Botelho began, in 1960, studies for the area of Chelas, with the participation of architects Francisco Silva Silva Dias, João Reis Machado, Alfredo Silva Gomes, Luís Vassalo Rosa and Carlos Worm and engineers José Simões Coelho and Gonçalo Malheiro de Araújo. The first version of the Urbanization Base Plan aimed to increase a multifunctional and socially diverse urban structure, integrated throughout the city. A set of high-density housing centers and a main core of mixed equipment and activities of local and widespread interest to the city was proposed. The morphological structure of these nuclei was based on this phase on the cellular and hierarchical distribution of the territory. The issue of valuing the natural accidents of the land arises in the various proposals as an asset in the landscape interest. But the biggest changes to the GEU plan were the densification of the housing area occupation, the expansion of green spaces and especially the change in the road structure scheme; two wide tracks intersect in the geometric center of the area, corresponding to the equipment core.

The plan was revised in 1963 by the same team, maintaining the priority objectives and changing urban concepts: the cellular structure was abandoned in favor of a linear structure, which allowed the so-called “intense urban life” zones to be created, which should constitute the main lines of urban structuring. This factor would allow the association of several urban activities and establish a coincidence between housing area and areas of intense urban life. The vitalization of urban routes through the rehabilitation of the street concept and the separation of car and pedestrian traffic was one of the most explored concepts in the planning phase.

The “bands of intense urban life” [4]

mixed several programs, with high-class housing being the most prominent. These axes accompanied by commerce connected points of cultural equipment, school, sports, nightlife hubs (cafes, cinema theatres…) and sources of service work (banks and public services).

The topographic characteristics of Chelas conditioned the plans and thus separated the occupation into two major axes parallel to the central valley, from which secondary axes were developed to structure five housing zones (I, J, L, M and N). The main core of equipment (zone O) would have a strategic position in the center of the urban network, to establish the connection between the two large axes to the east and west.

Chelas Urbanization Plan was presented in May 1964 to the Superior Council of Public Works (CSOP), to be submitted for approval. Costa Lobo, rapporteur of the opinion warned of several points that could be reviewed. The main one was to make the PUC convergent with the CML Master Plan in preparation. But one particularity that C. Lobo mentioned to the feasibility of the proposal was the need to “take advantage of the fixation of the population with strong purchasing power”. On 22 May of the same year, the plan was approved by the CSOP.

Road System

The main road network was based on the layout of two diagonals of direction NE/SO and NO/SE correspond to the long-distance axes that connect, in the first case, Moscavide and Areeiro, in the second, the Downtown area to 2.a Circular. The intersection of these is in the center of the mesh, where the central core of equipment and services would be installed. The local road network developed parallel to the central road with some contact points. The circulation of the local network would be mixed (car and pedestrian) in a closed circuit, that is, limiting the various zones.

Housing Areas

The residential buildings occupy the less inclined slopes, at maximum occupation densities, recovering the concept of the street as a uniting element and built framing, allowing a compact urban landscape of southern environment of the ancient city. In 11,500 dwellings divided into 5 categories, four according to DL No. 42,454 and rehousing, about 55,300 inhabitants were expected. These areas, in total of 318ha were allocated in 44% exclusively for housing, 5% for streets, 29% for open spaces, 13% for educational establishments and services and 9% for the tertiary sector.

Figura 4 – Proposed Urban Structure Diagrams. Source: GTH – Lisbon City Council Housing Technical Office – Achievements and Plans. Lisbon: Lisbon City Council, 1972, p. 43.

Green Structure

The rural state of the area created at the time an unpolluted air reserve that rocked the spread of industrial fumes from the riverside area. With the expansion of the city, the GTH team was aware of the need to maintain the balance: green areas take on various functions. From a total of about 160ha, the protection lanes of the main road network, the sports and recreational areas in the housing areas would be planted and two parks would be proposed: an eastern park of the city (Parque da Bela Vista) to the west, located in an area conditioned by the servitude of Portela airport; the Parque do Vale Fundão, symmetrical to the previous one to the east that served as a barrier against the smoke and dust of the riverside area.

Industrial Zones

The main industrial area planned, is along Av.a Marechal Gomes da Costa, as foreseen in the plan of the Office of Urbanization Studies (GEU). Another area would be destined for factories, between the railway and Madredeus District, ensuring the extension of the Main Avenue and access to the “2nd bridge over Tagus River”.

Equipment

The distribution of the equipment in the Chelas network is structured by the integration of intentions in a theoretical framework, which served the economic, cultural, recreational, and social activities of the population, constituting a sequence of poles of interest from the local center of the housing district (daily needs) to the main center (together with the city). The types of equipment were divided into four levels according to frequency of use and the radius of influence.

The 1st echelon encompasses daily equipment, integrated in housing areas such as elementary schools, daily stores, and children’s playgrounds.

The 2nd one handles daily or occasional use, such as secondary schools, daily or weekly sores, welfare establishments and nightlife centers (cafés, clubs…).

The 3rd is general and of occasional use, connecting points, such as headquarters of tertiary activities, churches, markets, restaurants, movie theatres.

The 4th, of general and regional use, mainly integrated in the connecting isthmus of zone O, gathers headquarters of tertiary activities (services), luxury commerce, hotels, cinemas, restaurants, and night clubs.

PublicTransports

At the time, the Rossio-Areeiro subway line was being completed (1966). The planned route that would serve Chelas, connected Rossio to Olivais, via Madredeus. GTH proposes a new route that would connect the Areeiro to the center of Chelas, and, successively, to the center of South Olivais and North Olivais.

The urban bus network ended at the outskirts of Chelas. The intention was to extend the existing lines of Areeiro to the center of Chelas and create new routes that would run along Via Central, South Olivais, Encarnação and North Olivais, as well as the creation of internal routes through the different neighborhoods.

The existing railway line from the center of Vila Franca was sufficient, with two stops, Chelas and Marvila and a station at Braço de Prata. It was only necessary to build road and pedestrian connections to the existing stops.

As for the suburban bus network, it was antecipated that Areeiro station would be overloaded and a new one was proposed in the centre of Chelas, connecting it to the national road network.

Figura 5 – General Plan of Zone I. Source: GTH – Lisbon City Council Housing Technical Office GTH – Realizations and Plans. Lisbon: Lisbon City Council, 1972, p. 53.

Figura 5 – General Plan of Zone I. Source: GTH – Lisbon City Council Housing Technical Office GTH – Realizations and Plans. Lisbon: Lisbon City Council, 1972, p. 53.

Looking at Chelas today

Unlike the Olivais, Chelas territory was mostly held by private owners. The City Council of Lisbon carried out the acquisition of land by “rapid and urgent expropriation” with the classification of “public utility”, taking more than a decade and leading to compensation to the owners that compromised the realization of the plan according to Decree-Law No. 42 454.

Chelas Urbanization Plan aimed to implement a cohesive grid with a strong urban image integrated in the surrounding areas, assuming itself as a challenge to the rationalist practice of the modern movement. The concentration of housing in high density linear areas alternated with free zones and equipment is the result of a criticism of the previous plans (North and South Olivais) with clear references to Toulouse-le-Mirail (George Candilis, Alexis Josic and Shadrach Woods) and Park Hill/Sheffield (Jack Lynn and Ivor Smith).

However, in the execution methodology, the pragmatic and “modern” concept of zoning in letter cells prevailed. The phasing in detailed plans of the zones, carried out at different times, compromised the original plan of linearly continuous cells, resulting in a space of high-density zones confronted by urban voids.

The “bands of intense urban life”, pedestrian streets of commerce, equipment and housing were subverted by the difficulty of attracting commerce. First floors began to contain more housing, making the strip a patio of residents, a strange corridor without identity, compromising the overall strategy of pedestrian paths and urban tracks.

The Plan was intended for a wide population diversity, but throughout the process, it was aimed mainly at rehousing and housing people with low purchasing power, to urgently respond to the demand of “housing for all”5 from the political and social context of April 25, 1974, revolution. The priority given to the construction of housing prevailed over the social infrastructure of planned equipment, jobs, or green spaces, contributing to the isolation of the area in physical and social terms.

But the main criticism, and perhaps the one that gathered the most consensus, was the dragging of the process over decades, which today we find unfinished, and the successive lack of political will to build here in the city. The initial model of a linear city was distorted with modifications made mainly at the level of buildings. Chelas is today a scattered district among interstitial and empty spaces with the urgent need to assume an identity and a place in the whole of Lisbon.

Figura 6 – Chelas Valley/County District. Author: Rodrigo Lino Gaspar, 2009.

Bibliography

ALARCÃO, Jorge de – Lisboa romana e visigótica. In Lisboa subterrânea. Lisboa: Lisboa 94, 1994, p. 58–63.

BOTELHO, J. Rafael et al – Plano de Chelas: estrutura urbana proposta: tipologia de família: elementos relativos à população que habita em barracas. Boletim do Gabinete Técnico de Habitação da Câmara Municipal de Lisboa vol. 1, nº 5/6/ 8/9, 1965.

BOTELHO, J. Rafael, e outros – O Plano de Chelas. Revista Arquitectura n.º 95, Jan-Fev 1967, p. 6-15.

Câmara Municipal de Lisboa – Plano de Urbanização de Chelas. In Habitação social na cidade de Lisboa, 1959-1966. Lisboa: Gabinete Técnico de Habitação, 1967, pp. 69–73.

CONSIGLIERI, Vítor; DUARTE, Rui Barreiros – A concepção dos espaços urbanos como acto político, entrevista a Francisco Silva Dias. Arquitectura e Vida nº 32, Novembro 2002, pp. 36–43.

GABINETE TÉCNICO DE HABITAÇÃO – Plano de Urbanização de Chelas. Lisboa: Câmara Municipal de Lisboa, 1965.

GABINETE TÉCNICO DE HABITAÇÃO – GTH: realizações e planos. Lisboa: Câmara Municipal de Lisboa, 1972.

HEITOR, Teresa Valsassina – A vulnerabilidade do espaço em Chelas, uma abordagem sintáctica. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 2001.

HEITOR, Teresa Valsassina – A expansão da cidade para oriente: os planos de urbanização de Olivais e Chelas. In Lisboa, conhecer, pensar, fazer cidade.

[1] De Gröer Plan – Lisbon Urbanisation Master Plan, initiated in 1938, which defined the main guidelines for the development of the city, completed and approved in 1948, prepared by architect-urbanist Étienne de Gröer, professor at Institut d’urbanisme de l’Université de Paris, who settled in Lisbon since 1938, at the invitation of the Mayor of Lisbon, Eng.o Duarte Pacheco.

[2] BOTELHO, J. Rafael, e outros – O Plano de Chelas. Revista Arquitectura n.º 95, jan-fev 1967, p. 8.

[3] Monumento Nacional, classified by Decreto nº17 954, DG, Iª série, n.º 34, de 11-02-1930 / Decreto de 16-06-1910, DG n.º 136, de 23-06-1910.

[4] GABINETE TÉCNICO DE HABITAÇÃO – Plano de Urbanização de Chelas. Lisboa: Câmara Municipal de Lisboa, 1965 p. 44-45.

[5] Reference to Article 65 of the Portuguese Constitution – Housing and Urbanism “Everyone has the right, for themselves and their families, to a dwelling of adequate size, in conditions of hygiene and comfort and that preserves personal intimacy and family privacy.