Valentina Bonifacio

valentina.bonifacio@unive.it

Università Ca’ Foscari, Venezia (Italy)

To cite this paper:Bonifacio, Valentina – From family to community album: portray of a Paraguayan company town. Estudo Prévio15. Lisboa: CEACT/UAL – Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa, 2019. ISSN: 2182-4339 [Availabre at: www.estudoprevio.net]. https://doi.org/10.26619/2182-4339/15EV

Received on 7 March 2019 and accepted for publication on 15 June 2019.

Creative Commons, licence CC BY-4.0: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

For about one hundred years, a heterogeneous group of indigenous and non-indigenous, Paraguayan, Argentinean and European people has been working in the tannin factory of Puerto Casado (Paraguay). In this article I discuss the attempt to create a community album of Puerto Casado by combining pictures belonging to the family albums of some of the ex-factory workers. I will argue that this change in scale – from family to community – enables the emergence of repressed ethnic, political and economic tensions that jeopardizes the concept of a “community” of ex-factory workers and proves to be a useful methodological tool for a collaborative research process.

Keywords: Paraguay; Chaco; family albums; Maskoy indigenous people; extractive industry; company town

Introduction: shifting scale

Puerto Casado is a small ex-company town of about 7.000 people located on the Western edge of the Paraguay River. As if emerging from a fantasy tale, its tannin factory has been functioning for exactly one hundred years – from 1896 to 1996 – thanks to a working force of mixed class and ethnic background: indigenous and non-indigenous Paraguayan people, Argentinean managers and European and Argentinean woking class migrants [Dalla Corte 2012]. Founded by the Spanish (naturalized Argentinean) entrepreneur Carlos Casado del Alisal, the factory and the 500.000 hectares of land surrounding it were sold by the Casado family in the year 2000 to Reverend Moon’s Unification Church. Nowadays, the tannin production has been replaced by a sawmill that exploits the remaining reserve of wood in order to sell the logs cheaply on the international market. Nowadays, Puerto Casado cannot be defined as a functioning “company town” anymore. In fact, compared to the 800 workers of the tannin factory in the 1990s, when I carried on my research in 2015 only 40 workers were hired as full time personnel in the saw mill of the Unification Church.

Between 2015 and 2016, for about ten months, I resided in Puerto Casado and Asuncion in order to carry on a research on the one hundred years of history of Carlos Casado’s tannin factory. In Puerto Casado I lived with a local teacher and I did regular trips to the nearby indigenous communities, where I had conducted fieldwork between 2007 and 2008. Out of a population of about 6.000 people, only a small number of them had been workers in the factory. Many of them had died, and others had moved away after the closing of the factory in 1996. Despite this, the sense of collective identity stemming from the common work in the Casado company was still very much present in both the discourses of the people and the objects scattered around the little town, and the new generation hadn’t forgotten. In the memory of the local people and institutions, Casado would have always been a company town. Through the help of the local teachers and thanks to the connections I had established during my previous fieldwork with the indigenous population, I could locate and conduct extensive interviews with about seventy ex-factory workers [Bonifacio 2017]. In order to make my work as public as possible, I also talked about it in the four local radios. By the end of my research period, I can say that most of the inhabitants knew me by name and were aware of what I was doing there.

The idea to collect family albums came during my first interview with an ex-factory worker, Don Ortega, who had been jefe de personal [head of personnel] of the Casado company from 1956 to 1996, when the factory stopped functioning. Born in 1928, Don Ortega was nearly ninety years old when I interviewed him, and because of his precarious health situation he could only barely speak. To facilitate the communication, I asked him if he preferred to show me pictures, a suggestion he appreciated as he immediately told his housekeeper to hand me over two cardboard boxes full of photographs. As it happens in most family albums, the photographs in the boxes pictured moments of his own life from a very young to a mature age, but also collective events and portrays of other people, somehow connected to his long life. It was immediately clear to me that the factory had always had a prominent role in Don Ortega’s life, as most pictures had been taken inside it or in close proximity. Partly historical documents and partly symptoms of an affective geography, they offered the possibility to be interrogated in their oscillation “between evidence and affect” [Edwards 2015: 236]. As shown by other authors, in fact, family albums are inevitably placed at the intersection between intimate and public events [Bouquet 2000], showing details of unique lives but also retaining the historical qualities of their time as part of their esthetic configuration [Sandbye 2014]. Moreover, some of the pictures were probably gifts, part of a visual economy of photographs [Poole 1997] where they circulated to strengthen or remind of non-familiar relationships: young men that Don Ortega introduced to the work in the factory and grown-up godchildren. Only partially and marginally the portrait of a family life, these photographs were the portrait of a lively community of workers and of Don Ortega’s positioning at its core.

The following analysis is based on the family pictures of about seventeen ex-workers who agreed to share their albums with me while I was conducting – as described earlier – a broader research on the history of the factory. At the same time, it includes part of the artworks that were produced in the context of an exhibition on the same topic called “Destiempo: dynamogram of Puerto Casado” that I organized with curator Lia Colombino and a group of Paraguayan artists in Puerto Casado, Asuncion, New York and Venice between 2016 and 2017 (for an overview of the artworks produced, see: www.unive.it/archfact). For the purpose of the exhibition, three of the artists (Silvana Nuovo, Ricardo Alvarez and Alfredo Quiroz) used some of the photographs I collected and included them in their artistic production. Rather than taking into consideration the whole exhibition, in this article I will focus on the paintings of one of the artists and on the community album that I created by selecting a certain number of pictures from the family albums that I encountered [picture 1]. After assembling the album, I showed it to the ex-workers – not only to the ones who shared their albums with me but also to those who didn’t – and wrote down their comments. By doing this, I was able to witness their reactions in front of other people’s family pictures [what is commonly called photo elicitation, see: Harper 2002; Samuels 2004], creating a visual and narrative portrait of the one hundred years of history of the Paraguayan company town.

The community evoked in the album is the imagined one that conformed the working body of the company town, but also the concrete one that for several months helped me to get in touch with the ex-workers and engaged with me in never ending conversations about their common history. I am not referring here, of course, to the contemporary 6.000 inhabitants of Casado, but to the ones with whom I worked more closely and who perceived themselves to be the representatives or the heirs of the community of workers who sustained the factory work for about one hundred years. The community album is thus an authored and a collective work at the same time: collective because through the use of family pictures, it restitutes the portrait of a sense of community created by decades of common work for the same company; authored, because through my intermediary role it also shows its contradictions and internal dismembering forces, as the ex-workers “community” was deeply divided through ethnic, political and class lines. It is indeed a community album in the sense that the faces and places that appear in the album are recognized as part of a common history by the people whose photographs constitute its content. At the same time, none of the workers would ever adopt it as his/her own community album because none of them would fully identify with the kind of heterogeneous community it identifies, preferring a conflict-free, neutral version of history able to deliver a harmonious vision of the past. This shift in scale in fact, from a family to a community album, not only involved a quantitative difference in the variety of contexts it revealed, but also a qualitative one. As I hope to make clear, old fractures, inter-ethnic tensions and repressed memories reemerged in my attempt to create a portrait of the ex-company town that would be able to hold all the different memories together.

1. Rituals, festivities, and the everyday life

One of the most common subjects in the pictures, apart from individual portraits, are celebratory moments where people gather together to celebrate. In the case of the non-indigenous ex-workers (I will refer to them from now on as Paraguayans, like indigenous people do), most festivities hold a close relationship with the factory life. In the examples, picture 2 shows a group of workers – recognizable as such by their helmet – gathering around a barbecue, probably after a trade unionmeeting. None of them wears the white helmet that characterizes the chiefs, and the man in the center with a light blue shirt is probably a delegate from the capital city. In picture 3 we can recognize Don Ortega, the head of personnel, sitting at the center with a white shirt, drinking beer with other young men inside the factory, probably celebrating with them the First of May, day of the workers. On the other hand, it is important to notice that none of the pictures ever portrays indigenous people celebrating together with Paraguayans – or by themselves – in proximity of the factory. The indigenous ex-workers (all of them belonging to the recently formed Maskoy ethnic group, see: Bonifacio 2013) never appear in First of May celebrations or in gatherings of the trade union. Their collective celebratory moments mostly concern ethnic rituals [picture 4] or Paraguayan dancing during school festivities [picture 5]. Picture 4 shows a group of women dancing in line for baile flauta, one of the few rituals still celebrated in the indigenous neighborhood of Puerto Casado. This picture, like many others belonging to Maskoy family albums,looks heavily damaged by water and humidity, bearing trace on its own material body of the different living conditions that affect indigenous people everyday lives with respect to the ones of Paraguayans.

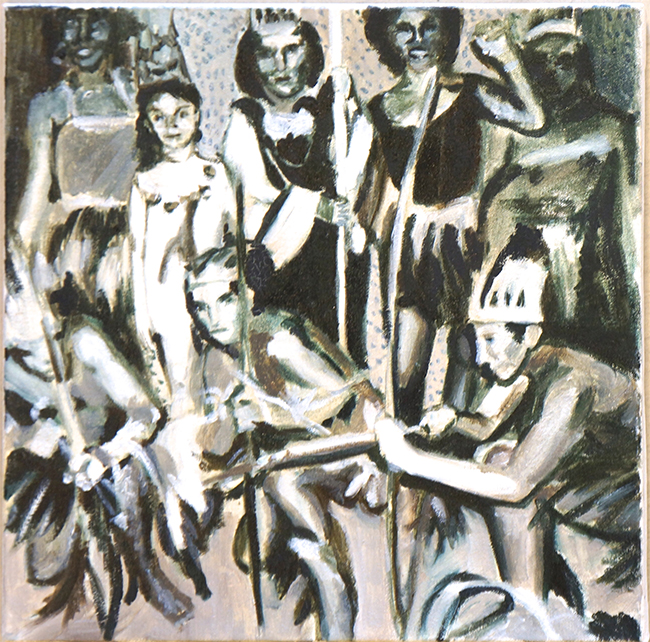

A few albums of non-indigenous families contain pictures of people celebrating the carnival, often dressed like the North American Native people that sometimes appear on television [Picture 6]. On the other hand, the ritual dresses of indigenous local people appear very different from the ones wore in carnival by Paraguayans, as we can see from the individual portraits taken during feminine initiation rituals in recent times [picture 7]. Working on these family albums, one of the artist – Silvana Nuovo – created for the exhibition “Destiempo” two paintings inspired by two different pictures (I will show here the paintings rather than the original pictures in order to give a sense of what was included in the exhibition). In the first one [picture 8], most likely from the end of the 1970s, a group of Paraguayans is dressed for carnival with straw skirts and a bow and arrow, imitating North American Native people. In the second one [picture 9], from the mid-1980s, a group of indigenous people is elegantly posing with the clothes that a Salesian missionary brought to them from Italy. Mirroring each other, the two portraits reveal a deep miscommunication, the coexistence of parallel words.

Focusing once again on the presence of the factory at the core of people’s everyday life, another subject constantly present and returning in the family albums of Paraguayans is the presence of industrial machines. The workers are often portrayed while (pretending to be) at work and more specifically while using or simply standing by one of the different machines inside the factory. Picture 10, probably from the 1960s, shows a group of workers next to the famous “Washington”. The “Washington motor”, often remembered in the interviews as being majestic and loud, generated the steam that made the production of energy possible inside the factory by burning logs. In the photograph, the workers seem to enjoy their time while leaning on it, as if its presence had already become a natural part of their lives. In a similarly staged way, picture 11 represents the portray of a worker pretending to be using a lathe machine but in fact dressing too elegantly for being really at work. In some other cases, no human being appears in the picture and the machines assume a leading role as the protagonists of the scene. For example, many Paraguayans exhibit a picture of the winchi (this is the name given by local people to cranes) hanging on the wall of their living rooms, even when the crane is clearly rusted and not functioning anymore. The portrait of the winchi is the ultimate representation of a nostalgic – mechanical past – that refuses to surrender to time [picture 12].

When taken outside rather than inside the factory, individual portraits are usually staged in front of buildings that are clearly recognizable as belonging to the Casado company. In fact, the oldest part of Puerto Casado is characterized by red-bricks, castle-like constructions that were built in between the 1910s and the 1930s. One of these old buildings is the central hotel [picture 13], that was used not only by the higher functionaries but also by the wood cutters that worked and lived in the interior of the Chaco region and came to Casado only once a month to collect their wage. Once again, the emphasis placed on the relationship between the individual and the company that is achieved by relying on the esthetic qualities of the landscape is absent from the pictures belonging to Maskoy people. Their portrays bear no trace of the factory or its surrounding, rather picturing in the background the church or their indigenous neighborhood.

To resume the previous considerations, we can say that while the factory and its related activities are placed at the core of the non-indigenous family albums, they don’t appear in the indigenous ones. The fact that indigenous people had the most dangerous, most tiring and less rewarding tasks inside the factory might be a reason for this omission, but this is true even in the case of Rene Ramirez, a Maskoy leader who worked both in the administrative office and in the company grocery store. Moreover, indigenous and non-indigenous people never appear in the same picture, not even accidentally. If we look at their everyday life through the lens of their family albums, we would say that indigenous and non-indigenous people in Puerto Casado lived in two parallel worlds, never crossing each other even though they shared the same town and the same working space. The segregation that appears in the family albums is probably a symptom of the segregation that happened in the everyday life, and shows an affective attachment to radically different places and memories.

This sense of disconnectedness is even accentuated by the presence in the Paraguayan family albums of carnival pictures where men and women dress-up like indigenous people bearing no visual reference to the ones they meet every day in the street and at work, but using instead as a model the ones they see on TV. Rather than emerging openly from the pictures, the tensions and conflicts between the two groups are expressed visually through omissions and differences. When I showed the community album to Paraguayan people, for instance, they were only interested in the parts that didn’t include Maskoy people, skipping their family pictures quickly as if they belonged to a different history.

2. Patrons, politics and the dark side of collective memories

Pictures containing portraits of powerful people, such as the factory patrons, godfathers, missionaries, militaries, politicians and football authorities are widely present in the albums and on people’s house walls. In the case of patrons and politicians the photographs serve as a display of alliances and personal power, even though in the case of Maskoy people they are usually the result of gifts rather than proudly acquired trophies. Indeed, the only pictures of “white” people that appear in the Maskoy albums are pictures of nuns, missionaries and godparents.

In one of the oldest pictures I found, belonging to an uncle of a Maskoy friend (Amada Ramirez), a group of nuns and priests is surrounded by kids and the caption says: “the Reverend Mother is looking at the soup in the Toba settlement” [picture 14]. The caption is written with beautifully crafted calligraphy, and it is fair to assume that it was taken by a missionary and given to its Maskoy owner as a gift. Just like in the case of Don Ortega, who received many pictures from his godchildren and from the workers he helped, these pictures participate to a visual economy of photographs aimed to express and testify personal alliances [Edwards 2012]. In another, most recent picture [15], a priest (father Ballin) is surrounded by kids inside a community. The picture was taken by the Polish missionary of Puerto Casado, Father Sislao, and then given to Antonia, the young Maskoy woman standing on the left of the priest. Expressing a similar purpose, I also found in Antonia Portillo’s family album a picture where I appear with her, her husband, Amada Ramirez and my godchild (Amada’s daughter), and that I gave to her more or less 10 years earlier, when she I was living with her during my PhD fieldwork in 2006-2007 [picture 16]. In a third picture [17], Amada Ramirez is posing in between her godmother and her godfather, Don Hermosa, the cattle ranch manager of the Casado company. The picture belonged to Amada’s father, who was at the time interested in strengthening his ties with Don Hermosa.

Compared to the Maskoy family albums, priests and missionaries appear very rarely in the Paraguayan ones. As we said, their pictures are more frequently related to the working context, even though the authorities of the company rarely appear in them. In fact, the owners and the Argentinean managers of the factory are only present in two of the albums: the first belonging to Don Hermosa, the already mentioned [picture 17] Paraguayan cattle ranch manager of the Casado company, and the second to Tarcisio Sostoa, a local leader of the Colorado Party. In picture 18, we can see Don Hermosa on the left wearing a Paraguayan woolen poncho and on his right two members of the Casado family and the Argentinean manager of the company cattle ranches, looking visibly different and wearing plastic ponchos that are never used by local people.

If the image of the owners of the factory belongs to a shared, relatively non conflictive memory of the past, the pictures of politicians were the most delicate ones to insert in the community album. By definition, the memories they re-awoke were marked by contrasting emotions depending on which political side the viewer belonged, especially in a context – that of a dictatorship – where politics had such a prominent role. For this reason, the more controversial pictures in the community album are the ones belonging to Tarcisio Sostoa, an important leader of the Colorado Party during Stroessner’s dictatorship, and then governor and congressman during the first years of the so-called transition to democracy (1989-1994). Despite being considered a company enemy, Sostoa appears in the pictures while hugging Marcos Casato Sastre [picture 19], one of the heads of the Casado company, and his albums are full of portraits with important politicians, including General Stroessner himself.

While leafing through the community album, the ex-workers always skipped very quickly the parts where pictures of politicians and political demonstrations appeared on the pages. This avoidance of the political history of the past is a way to avoid open conflicts and also to prevent old fractures from emerging again. In a relatively small place like Puerto Casado, it seemed important to forget any tension occurred with the neighbors in the recent past. As one friend from Puerto Casado warned me once: “Remember that you are collecting the history of Casado, you shouldn’t be doing politics!”. Still too emotionally charged to be able to be archived as “history”, the memories of political figures and events share an unsettling character in the pages of the community album. In fact, while their role in family albums can be kept under control and shared only with specific individuals, if made public they let old fractures and tensions reemerge. The ideal community album would have been for the Paraguayan ex-workers an album focused on the memories of work, one that could show the golden age of the Casado company, when most people had jobs, and Puerto Casado was known all over the country for being a center of civilization and progress. Even the pictures which portrayed events and meeting organized by the trade union didn’t elicit any significant political memory, and the viewers rather made comments on the festive aspects of the gatherings, mentioning names and pointing at the quantity of beer and roasted meat that had been consumed.

One of the most revealing moments I had while showing the community album to the ex-workers has been the viewers’ reaction to a picture of August Sabino Montanaro, Stroessner’s minister of interior from 1968 to 1989 (the year when the dictatorship was overthrown). In the picture he stands in front of the Paraguay River, a clear sign that the photograph was taken during a visit to Puerto Casado [picture 20]. Even more than the image of General Stroessner, the sudden appearance in the photo-album of Sabino Montanaro provoked very strong emotional reactions on the part of the ex-workers: many of them burst in frightened exclamations, and two of them shouted at an invisible audience “Hake pombero! [beware the pombero!]”. The reference in this case is to a mythical Guarani figure, the pombero, a hairy monkey-like man who hides in the woods and scare people in order to get them lost, or sneak into young women’s bedrooms to make them pregnant. Montanaro was a recurring figure in Sostoa’s family album, and being an important historical figure I thought it would be appropriate to include him in the album. Nevertheless, his presence very clearly transformed the community album not in a site for longing about the past and its beauty, but in a place for confronting uneasy and repressed memories [Didi-Huberman 2006]. In this sense, the community album elicited a very different set of emotions with respect to most family ones.

Conclusion

The attempt to curate a community album which would be able to represent and convey a shared vision of the one hundred years of history of Carlos Casado’s tannin factory, starting from the single family albums that the ex-workers had shared with me, has proved to be a very complicated task to achieve in my research. More than representing the collective portrait of a town in a certain period of time, and despite containing pictures from actual family albums, the community album I realized for the final exhibition was my own interpretation of history, bearing traces of the ethnic barriers and of class and political tensions of the “community” of ex-workers that was the result of one hundred years of history. Working with the community meant bringing to light its reverse, namely the absence of a homogeneous community that went beyond the fact of sharing a same geographical space and a common past as employee of the Carlos Casado S.A. After receiving the first comments about the album on the part of the viewers, instead of censoring its most conflictive pictures I decided to exhibit it as it was, in the hope that it might represent a tool for the future generations of Puerto Casado to explore history and memory not as a straight line but – to use Aby Warburg’s expression – as a tangle of snakes that interweave and unravel confronting the present in uncomfortable ways [Didi-Huberman 2006].

Image 1– Example from one page of the family album containing my notes and an anonymous sign, added during the exhibition, which says “Plutarco Gomez, tornero [lathe machine operator].

Image 2– Fernandez family album.

Image 3– Don Ortega family album (1).

Image 4– Ramirez family album (1)

.

Image 5– Portillo family album (1).

Image 6– Don Ortega family album (2).

Image 7– Portillo family album (2).

Image 8 – Silvana Nuovo. 2016. Serie “Sociedad anónima”. Oil on canvas (1).

Image 9 – Silvana Nuovo. 2016. Serie “Sociedad anónima”. Oil on canvas (1).

Image 10 – Di Giacomi family album.

Image 11 – Amarilla family album.

Image 12 – Crane picture hanging on the wall in Don Ortega’s living room.

Image 13 – Don Ortega family album. A couple is posing in front of the hotel, recognizable by the castle-lace on the upper part of the building.

Image 14 – Amada’s uncle possession.

Image 15 – Portillo family album (3).

Image 16 – Portillo family album (4).

Image 17 – Ramirez family album (2).

Image 18 – Hermosa family album.

Image 19 – Sostoa family album.

Image 20 – Augusto Sabino Montauro (Sostoa family album).

Bibliography

BONIFACIO, V. – Meeting the Generals. A political ontology analysis of the struggle for land of the paraguayan Maskoy in the 1980s. In: Anthropologica 55(2). The Journal of the Canadian Anthropological Society, 2013, p. 385-397.

BONIFACIO, V. – Del trabajo ajeno y vacas ariscas. Puerto Casado. Genealogías (1886-2000). Biblioteca Paraguaya de Antropología, Vol. 108. Asuncion: CEADUC (Centro de EstudiosAntropológicos de la Universidad Católica Nuestra Señora de la Asuncion), 2017.

BOUQUET, Mary – The family photographic condition. Visual Anthropology Review16(1), 2000, p. 2-19.

DALLA-CORTE Caballero, G. – Empresas y tierras de Carlos Casadoen el Chaco Paraguayo. Historias, negocios y guerras (1860-1940). Asunción: Intercontinental Editora, 2012.

GEORGES, Didi-Huberman – L’immagine insepolta. Aby Warburg, la memoria dei fantasmi e la storia dell’arte. Bollati Boringhieri, 2006.

EDWARDS, Elizabeth – Anthropology and photography: A long history of knowledge and affect. Photographies 8(3), 2015, p. 235-252.

EDWARDS, Elizabeth – Objects of affect: Photography beyond the image. Annual review of anthropology 41, 2012, p. 221-234.

HARPER, Douglas – Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Visual studies 17(1), 2002, p. 13-26.

POOLE, Deborah – Vision, race, and modernity: A visual economy of the Andean image world. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997.

SANDBYE, Mette – Looking at the family photo album: a resumed theoretical discussion of why and how. Journal of Aesthetics & Culture 6(1), 2014, p. 1-17.

SAMUELS, Jeffrey – Breaking the ethnographer’s frames: Reflections on the use of photo elicitation in understanding Sri Lankan monastic culture. American behavioral scientist 47(12), 2004, p. 1529-1550.

Biographical note

Valentina Bonifacio is a researcher and lecturer in visual and applied anthropology at the Ca’ Foscari University in Venice. In 2009 she obtained a PhD in Social Anthropology with Visual Media at the University of Manchester (UK). Since 2004 she is carrying out fieldwork in Paraguay, where she has also worked for a few years in the field of international cooperation. Committed to a multi-disciplinary approach, besides writing articles she has filmed documentaries (see, for instance: “Casado’s Legacy”) and organized an exhibition about her topics of research (Destiempo: dynamogram of Puerto Casado).