João Belo Rodeia

rodeiapt@gmail.com

Architect, Invited Auxiliary Professor at Da/UAL

To cite this paper: RODEIA.João Belo – Brésil – vieux Portugal, Le Corbusier discovers Brazil in1929. Estudo Prévio 17. Lisboa. CEACT/UAL – Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa, 2020. ISSN: 2182-4339 [Available at: www.estudoprevio.net]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.26619/2182-4339/17.2

Review received on 7 June 2020 and accepted for publication on 19 June 2020.

Creative Commons, licença CC BY-4.0: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

This paper discusses the possibility of Le Corbusier (1887-1965) having seen Portugal by way of Brazil and that that vision will have led to his first visit to Brazil, in 1929, described in “Précisions sur un état présent de l’architecture et de l’urbanisme” (1930), written just before the timeline we will be analysing in this paper.

This paper will include scattered information in available sources that show that, among Le Corbusier’s connections in Paris, there were several Portuguese, Brazilian-Portuguese and Brazilian friends, besides those he directly contacted on his trip to South America in 1929. This interaction, always associated with “Précisions”, makes this a plausible possibility, as in the referred text, Le Corbusier makes several urban planning suggestions for Brazil, in particular, for Rio de Janeiro. Moreover, he also dedicates a part of Brésil – vieux Portugal to discussing the future of Brazil. The interpretation of this latter text opens the possibility for further research.

This article is closer to an essay, defined as “ciencia, menos la prueba explícita”1 by José Ortega y Gasset (1883-1955) resorting to argumentative discourse and more open to interpretation though it also includes facts, circumstances, and anecdotes, crucial to state a point of view and its readability.

Keywords: Le Corbusier, Brazil, Portugal

Brésil – vieux Portugal, Le Corbusier discovers Brazil in 1929

In September 1929, Le Corbusier travels to South America passing through Lisbon and returns to France in December of that year, a few days before Christmas, probably also via Lisbon. As far as we know, that will be his first and only (double) passage through Portugal. Based on his stay in America – Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Brazil – Le Corbusier will write a passionate book “Précisions sur un état présent de l’architecture et de l’urbanisme” (1930), an important text that evidences the changes in his theoretical thought from the 1920s to the 1930s, heavily influenced by his visit to Brazil2. This is the only text in which he briefly, indirectly or directly, refers to Portugal, though these references are always linked to Brazil. For Le Corbusier, Portugal is always linked to Brazil as part of a double journey: a transatlantic one that includes his stay in Brazil, and a different type of journey, as in “Prologue Américain”3 and especially in “Corollaire Brésilien”4. These two journeys are inseparable, as stated by Paulo Prado (1869-1943), LeCorbusier’s best Brazilian friend.

Besides this trip, we must also mention the intricate network of relations that Corbusier had in Paris in the 1920s. If we go back to 1917, the year he immigrated from La Chaux- de-Fonds, in Switzerland, to Paris, the then Charles-Édouard Jeanneret had a close relationship with painter Amedée Ozenfant (1886-1966) to whom he will be introduced by Auguste Perret (1874-1954), his former patron. Soon, they would start a long and fruitful artistic and professional relationship, which would last until 1924. In 1917, Ozenfant was already a well-known painter, so he probably felt enchanted by the rather young Jeanneret. Ozenfant had been living in Paris since 1905, having graduated at Académie de la Palette in Montparnasse, where he met Sonia Terk (1885-1979), a Ukranian who would become his friend and would marry painter Robert Delaunay (1885-1941) in 1910. The couple meets Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso (1887-1918), among other modernist Portuguese painters who lived in Paris5. They moved to Portugal between 1915 and 1916 to run away from WWI and would pass through Lisbon and eventually live in Vila do Conde with painter Eduardo Viana (1881-1967) after briefly staying in Monção, and in Valença do Minho. Besides their reunion with Amadeo, they also met artists José de Almada Negreiros (1893-1970) and José Pacheco (1885-1934), and spend happy and creative time in the sun, the sea, and the Portuguese colours. At Sonia’s initiative, poems by Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918) and Blaise Cendrars (1887-1961) were published in the short-lived magazine Portugal Futurista (1917)6. In fact, Cendrars was Delaunay’s friend and, after their return to Paris in 1920, it is possible that they attracted him to Portugal. The poet would remain a close friend of Le Corbusier. They had both been born in the same year and in the same Swiss town and their houses were rather near one another, yet they would only become close in Paris from 1922 onwards7.

Ozenfant had a crucial role in Le Corbusier’s name as a painter and as a public personality in Paris. Ozenfant invites him to co-author “Après le Cubisme”, published in December 1918, the first artistic postwar manifesto in Paris and an exhibition with Ozenfant and Le Corbusier’s work in Galerie Thomas. They advocated Purisme, inseparable by fixity, timelessness and transnationality of primary forms associated to a new time. This concept would be at the core of Corbusian architectural theory in a machiniste framework, which will suffer changes throughout that decade. Two years later, in 1920, Ozenfant, Le Corbusier and Paul Dermée (1886-1951) founded the magazine L’Esprit Nouveau (1920-1925), whose name evoked Apollinaire and Paul Valery (1871-1945). There, Le Corbusier will publish his initial texts that will become part of “Vers une Architecture” (1923), an international best-seller.

Through Ozenfant (and the magazine), Le Corbusier will meet many artists, gallery owners and marchands. Among many others, besides the Delaunays and their Portuguese paintings, including Robert Delaunay’s, “La grande portugaise” (1916), we may mention Georges Braque (1882-1963) and “Le Portugais” (1911), the Spanish Juan Gris (1887-1927) and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), the Lithuanian Jacques Lipschitz (1891-1973) and Fernand Léger (1881-1955), two of his best friends. They all published their work in “L’Esprit Nouveau”. (Almost) all painters whose first modern work will arrive to Sao Paulo (and to Brazil) from the early 1920s onwards by millionaires Paulo Prado and Olívia Penteado (1872-1934), whose fortune was due to coffee production

“L’Esprit Nouveau” was probably known among the Portuguese artists in Paris, whether residents and visitors, but it was definitely known in Sao Paulo since its foundation, namely by writers Mário de Andrade (1893-1945) and Oswald de Andrade (1890-1954), who were its subscribers, and by painters Anita Malfatti (1889-1964) and Tarsila do Amaral (1886-1973). The magazine would, in fact, lead to the famous Semana de Arte Moderna (Week of Modern Art) in Sao Paulo in 1922, which is associated to the emergence of modern “nationalist”8 Brazilian avant-garde, directly linked to the promotion and patronage by Prado and that of his French wife Marinette Prado (?), or that by Penteado, Parisian habitués, including António Ferro (1895-1956), a young journalist and writer belonging to the Portuguese literary and artistic avant-garde.

Ferro, a Paris lover who would travel there often and a world citizen in 1920s Lisbon, will spend a long time in Brazil at this time and will meet all the referred important figures and others, such as Ronald de Carvalho (1893-1935), co-director of the short-lived Portuguese-Brazilian avant-garde magazine Orpheu (1915), of which Ferro had been an editor. He will, in fact, marry by power of attorney the Portuguese poet Fernanda de Castro (1900-1994), who will then travel to Brazil. Oswald and Tarsila will be their best man and maid of honour. Tarsila will even do a painting of Fernanda. Several reunions will take place during the 1920s and Ferro will regularly exchange letters with Mário and Oswald, among others. Ferro will attend at least the first of Tarsila’s two exhibitions in Paris, in Galerie Percier in 1926, and, that same year, he will publish a text on the painter in the magazine Contemporânea (1922-1926)9, as well as a text in the catalogue of her first individual exhibition in Brazil, in Palace Hotel, Rio de Janeiro, in 192910. Already in the 1930s, Tarsila will dedicate a text to Fernanda’s11 book of poems. Both women corresponded regularly.

Both Portuguese and Brazilian artists were attracted by the training possibilities and by the creative and bohemian atmosphere of Paris. Tarsila will be in Paris in 1920-21 and will be followed by Anita, who will live there from 1922 to 1928. In 1923, Tarsila will return to Paris, this time with Oswald, her lover, from where they will travel to Portugal between January and February 1923 – where they will reunite with Ferro and Fernanda – and to Spain. The relations between Portugal and Brazil were very intense at that time. Brazil, where Portuguese culture was still very strong, was the main destination for Portuguese immigration, as well as a refuge for adventurers, intellectuals, and politicians. Portugal, where Brazilian culture was disseminated and enjoyed, besides being important to all those that studied the past of Brazil, remained a destiny for Brazilians wishing to attend university and a step on their way to France and on their way back to Brazil.

The coming and going by sea was never ending. The main navigation companies, including the French ones, would stop in Lisbon on their way between Europe and South America. And as the ships slowly entered the city and the river Tagus going past Cascais and Serra de Sintra, all those travellers would discover or rediscover Lisbon and its landscape, orographic profile, topography and its relationship with the river and the sea, which reminded them of many contemporary seaside cities in Brazil, from Salvador da Bahia to Rio de Janeiro. The stopover in Lisbon, without berth, lasted several hours (many boats would slowly go in and out of the ship, to load and unload cargo) as described by Lucio Costa (1902-1998) on board Bagé in 1926, so there was plenty of time to roam the city12.

In “Précisions”, Le Corbusier refers to Paulo Prado as his best Brazilian friend13, which is why he deserved special attention. Prado was born in one of the most powerful families in Sao Paulo, a Portuguese family whose roots dated from 18th century, and he was more than a wealthy Brazilian who often stopped at Lisbon on their way to Paris. He was a well-travelled, educated, art collector (and book lover) who would become known as an homme de lettres in the 1920s, since he reflected on the past and the future of his country (and of Sao Paulo) and bridged the gap between the past and modernity with the concept of “brasilidade”. When he was in his twenties, Prado travelled to Paris at the time of Belle Époque and lived in Rue de Rivoli in his uncle’s residence, Eduardo Prado (1860-1901), until the end of the 19thc. Eduardo Prado was known for his refined taste and his interest in Brazil’s colonial history and would have been the inspiration for the character Jacinto in the novel Cidade e as Serras (1901) by José Maria Eça de Queiroz (1845-1900), one of his closest friends and also a lover of Paris.

Paulo will be part of the Portuguese-Brazilian elite that would meet either in Neuilly, at Eça’s house, or at Rue de Rivoli. In these gatherings, attended by many Portuguese and Brazilian14 personalities, we could find writer José Ramalho Ortigão (1836-1915) and, above all, historian Joaquim de Oliveira Martins (1845-1894), author of “O Brasil e as Colónias Portuguesas” (1880). This will be an important part of Paulo’s education. His wit and critical spirit would come from Eça and his historical perspective of Brazil and Portugal from Oliveira Martins15, both in terms of glorifying the 15th century Portuguese (the Discoverers and the first settlers) and in denouncing the decadence that followed, and in the regeneration, a kind of return of the heroes sung by Camões, now projected in contemporary and future Brazil, in the recreation of a Portugal independent of Europe, modern and Brazilian, a perspective that, from 1917 onwards, will appear in all his books up to Retrato do Brasil – Ensaio sobre a tristeza brasileira (1928).

But there is more. His uncle would influence his taste for collecting documents on Brazilian history, geography, and ethnography. He would also become a frequent customer of antique dealer Charles Chadenat (1859-1938) at Librairie Américaine, near Quai des Grands-Augustins, in Paris, famous for its catalog of books, maps and colonial documents in his shop’s Brazilian section. And, through his uncle, he would start and maintain a long friendship and contact with the Brazilian historian João Capristano de Abreu (1853-1927), who was also influenced by Oliveira Martins, who advocated that terrestrial and river paths were relevant for colonial history, again linking history and geography, as in Caminhos Antigos e Povoamento do Brasil (1930).

From Capristano Prado he would have probably learned about the several sources, from “Diário de Navegação”, by Pêro Lopes de Sousa 1500-1532 (1927), with an introduction by Capristano, through the extraordinary scientific expedition by Portuguese-Brazilian naturalist Alexandre Rodrigues Ferreira (1783-1792)16, to “Corografia Brazilica ou Relação histórico-geográfica do Reino do Brazil” (1817) by the Portuguese priest Manuel Aires de Casal (1754-1821), where the letter, Carta de Pêro Vaz de Caminha, rediscovered in 1773 inTorre do Tombo appeared for the first time. Prado considered it a first portrait of Brazil “na sua idílica ingenuidade (…), primeiro hino consagrado ao esplendor, à força e ao mistério da natureza brasileira (…)” where you “percebe-se o encantamento do maravilhoso achado que surgia diante dos navegantes depois da longa e incerta travessia”17. Pêro Vaz de Caminha describes paradise. This is the vision of Brasil that Le Corbusier will learn from Prado before and during his trip in 1929, just as had happened to Cendrars, as we will see later.

Their link with Brazil started in Paris, where Prado would spend his summers. From the early 1920s onwards, this group of Brazilians in Paris is known to have met with Le Corbusier’s closest friends and eventually with Le Corbusier himself. Right after his trip to Portugal in the beginning of 1923, Tarsila (with Oswald) met Cendrars in May18 and, through him, in October, she met Léger 19in his office20. It is possible that Le Corbusier, either taken by Cendrars or Léger, met Tarsila still in 192321, since there is a portrait of her by Emiliano Di Cavalcanti (1897-1976)22. Tarsila (with Oswald) would also be the link between Prado and Léger and Cendrars23. The French painter will be one of the first to sell his paintings to Prado24 (and to Penteado), with whom he would regularly meet in the 1920s25. And after a casual meeting at Librairie Américaine, through Oswald26, Prado would later invite Cendrars to visit Brazil, which would take place in 1924.

Léger and especially Cendrars would be the ones who would raise Le Corbusier’s interest in Brazil through conveying to him the vision they had been told about in Paris. After 1925, they would encourage him to visit Brazil, mostly at the pretext of Planaltina, the announced new capital of Brazil27. It is also possible that Le Corbusier crossed paths with Prado at Tarsila’s studio28, but Léger would have been the one who would bring them closer in 192629, as we know they met and maintained their contact since then30, as well as attended the same salons, such as that of Isabel Dato Barrenechea (Spain, ?-1937), Duchess of Dato, Eugenia Errazuris (Chile, 1860-1951) or Victoria O’Campo (Argentina, 1890-1979). This would have led to Le Corbusier having been invited by Alfredo Gonzaléz Garaño (1886-1969) and O’Campo31 to lecture in Argentina in 1929, and to Prado becoming his best Brazilian friend.

In 1924, aboard the Formose, Cendrars travels to Brazil for the first time at Prado’s expenses Their close friendship would be long lasting. He would go back to Brazil in 1926 and 1927, always via Lisbon, where he would also travel to at least in 1929 and in 1934. He would translate A Selva (1930) into French (“Forêt Vierge”,1938) a novel by the Portuguese novelist José Ferreira de Castro (1898-1974) based on his direct experience in the Amazon Forest. Cendrars fell in love with Brazil on his first visit, which lasted about six months, and the same would happen to Le Corbusier. He went to Prado’s tropical garden mansion at Avenida Higienópolis, in Sao Paulo, he was honoured by the city’s media, he lectured to a packed room in Conservatório Musical de Sao Paulo. The conference would include an exhibition by Paul Cézanne (1839- 1906), Delaunay, Léger, Albert Gleizes (1881-1953), Tarsila and Lasar Segall (1891- 1957), all belonging to Prado and Penteado32. He visited Penteado’s salon in Sao Paulo and parties with the local elite and was welcomed and cherished by all. He witnessed the 1924 revolution, attended carnival at Rio de Janeiro with Penteado and the 22 Group, including Tarsila and Oswald. With this group, he would travel through historical cities in Minas Gerais in search of “brasilidade”. In lush Sao Martinho, Prado’s coffee plantation near Ribeirão Petro, he experienced tropical heat, slept in the hammock on the balcony and wrote poetry. They talked about everything, they talked about Brazil, “Il m’a fait lire tout ces livres, m’initiant à tous ses travaux”33, says Cendrars. He would know Brazil through Prado’s eyes, that of the future Retrato do Brasil. However, as would happen to Le Corbusier, he did not share Prado’s pessimism of the “three sad races” – the Portuguese, the Indian and the Negro – who, for the poet, represented party, joy and optimism. He loved the mixture of people and the mixed people. And he would become emotional at the sight of the landscape and the Brazilian cities, as if he had returned to the origin of everything and travelled to a new world. He was happy and made Brazil his personal and intimate topos, (his) paradise on earth

On his return to France, Cendrars would write his first book Feuilles de Route (1924), illustrated by Tarsila and dedicated to his friends from Sao Paulo and from Rio de Janeiro, the first one being Prado. Many poems were dedicated to Brazil and, in 1926, at the time Tarsila had her individual exhibition at Galerie Percier, he associated six poems on Sao Paulo to the paintings:

“J’adore cette ville, Saint Paul est selon mon cœur, Ici nulle tradition, Aucun préjugé, Ni ancien ni moderne, Seuls comptent cet appétit furieux cette confiance absolue cet optimisme cette audace ce travail (…) Tout les pays, Tous les peuples, J’aime ça, Les trois vieilles maisons portugaises qui restent, sont des faïences bleues”34.

Besides “Pedro Alvarez Cabral”, which was part of his Brazilian cycle, he wrote two poems on Portugal, “Porto Leixões” and “Sur les côtes du Portugal”: “Du Havre nous n’avons fait que suivre les côtes comme les navigateurs anciens”35. Le Corbusier trip to Brazil resulted from the invitation by Asociación Amigos del Arte to go to Buenos Aires, sponsored by the city’s university36. It was a last-minute trip, promoted by Prado, who organized it in a short period of time37. However, it was not an improvised trip. Firstly, because Le Corbusier was interested in it, encouraged by Léger and especially by Cendrars and Prado. Secondly, because Le Corbusier would have prepared the trip in advance, since “on n’entreprend pas un si long voyage à la légère”38, as mentioned in “Précisions” and in his letters to his mother and the documentation in Brazil (maps and photographs) sent by Cendrars39, as well as Feuilles de Route. Thirdly, because he needed to prepare the trip by learning about the history of Brazil40, so that he would know what to expect, to maximize traveling, schedule conferences, attract new contracts, because, as always, there was an obvious interest in having work requests: “Que Pierre affûte ses crayons et ses dessinateurs. Nous allons construire l’Amérique”41. And he knew about the potential offered by Sao paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Planaltina.

Until he immigrated to Paris, Le Corbusier (still Jeanneret) would have little knowledge of Portugal, unlike that of Spain, since “Dom Quijote” (1605) by Miguel de Cervantes (1547-1616), was in his library, where, in any case, we could find “Candide” (1759) by Voltaire (1694-1978), which talks about the 1755 earthquake in Lisbon and which he referred to in “Précisions”42. However, in 1929, Le Corbusier could pinpoint Portugal on a map. There were (few) pieces of news about Portugal in the French newspapers in the 1920s, such as on the 1926 military coup or, from 1928 onwards, news about Oliveira Salazar (1889-1970). And there were people who would talk about Portugal, like the Delaunays or the Portuguese journalist Homem-Christo Filho (1892-1928), a close friend of Benito Mussolini (1883-1945), who would preside the Syndicat de la Presse Etrangère in Paris, and who frequent the same salons and galleries as Le Corbusier. And he would occasionally meet Portuguese artists who lived in or visited Paris. Moreover, on his lectures in Madrid, Spain, he would meet Almada Negreiros, then living in Madrid43. Still, the Portugal he knew came mostly from Brazil (and Cendrars). His knowledge was not deep, but it fostered his interest in the country. In 1929, the date of his trip, he felt prepared to conquer Brazil44.

On 14 September, around 1 a.m., Le Corbusier would leave Bordeaux aboard the Massilia45, a liner from Compagnie de Navigation Sud-Atlantique and, two days later, he would arrive in Lisbon, just like Cendrars on his trip to Brazil. The ship had passed the coast of Cantabria and Galicia all the way down to Lisbon. The weather was excellent, and Le Corbusier was very happy and would spend his time drawing on his travel journal. Some of those drawings include drafts of the coast46. and of the entering and leaving the river Tagus, because “il faut savoir être en état de jugement, toujours”47. Le Corbusier captured some of the basic features of the city, such as its layout, orographic and river organization, its openness to the sea. He would find similar features in Rio de Janeiro, though at a much bigger scale. It was his first time in the Lisbon of “Candide” and he knew the city was linked to the colonization of Brazil and that the stopover would last more than enough time for him to get ashore. We assume that was what happened, because he would send a letter from Lisbon – “cette lettre partira de Lisbonne”48 – to his mother and would draw a bullfighting scene on a date he was in Lisbon49. He would not write about this, though, except when he mentions the “marsouins (…) à Lisbonne”50, just like Cendrars did in “Sur les Côtes du Portugal”. But his experience in Lisbon would definitely help him confirm that Rio was “une ville gaie, portugaise, charmante”51, with “boulevards en mosaïque noire et blanche, formant un cirque immense, marqué par (…) la mer qui vient mourir sur une plage fine, contre le trottoir”52.

He would spend about three months away from France, two travelling through South America and one to cross from Bordeaux to Buenos Aires and back. He would arrive to the capital of Argentina on 28 September, after doing a stopover in Rio de Janeiro, having gone on a short night tour around the city53, afterwards in Santos and in Montevideo and finally arriving in Buenos Aires. He drew the whole trip. During the trip, he would write the ten papers for the lectures in Buenos Aires54, which took place on 3 to 19 October, a kind of theoretical summary – “C’est une Bible”55 – he wrote in “Précisions”56. However, “Prologue Américain” and “Corollaire Brésilien” would be written later, the first on his return to France aboard the Lutetia on 10 December57,and the second already in Paris, on 27 January 193058. The two would be written just before the first flight to Assunção, in Paraguay, a unique moment in his South American trip – “voyage formidable sur le centre de l’Amérique. Fleuves colossaux, agrandis par l’inondation: ce sont des bras de mer. Lecture de la nature vierge”59 -, about his visit to Montevideo and, above all, its comparison with Brazil. This would have such an impact that it would lead to Le Corbusier’s conclusions in “Précisions”, and his Feuille de Route, which everything indicated was not initially considered.

Le Corbusier’s stay in Brazil was very similar to that of Cendrars, though packed into three weeks. Their passion for the country would also be similar, also very deep. Le Corbusier travelled from Buenos Aires in the liner Giulio Cesare, where he met Josephine Baker (1906-1975), and disembarked on 17 November in Santos, from where he travelled by train to Estação da Luz in Sao Paulo. He would stay in Sao Paulo until 2 December at the invitation of Círculo Politécnico. Prado welcomed him and placed him in Hotel Terminus in Rua Brigadeiro Tobias, right in the centre of the city.

His agenda would be intense60. He would meet with the Mayor José Pires do Rio (1880- 1950) on the 19th. He would hold two (paid) lectures at Instituto de Engenharia, one on architecture, on the 21st, on the day Gregori Warchavnchik (1896-1972) took him to visit his pioneer modern houses, and another on urban planning, on the 26th. Before that, he was honoured by the Municipality on the 23rd and, on that same day, he was taken on a flight around the city by Georges Corbisier (1894-?), who had an important role in the building of the city and was a friend of Alberto Santos Dumont (1873-1932), an aviation pioneer. He spent the time drawing. He also had fun. On the 27th, he attended a show by Josephine Baker and took her to a party organized by Warchavnchik. He took Baker to another party (after the 25th), this time at Tarsila and Oswald’s house, with Mário de Andrade. He enjoyed the frenzy Sao Paulo, its vitality, its machiniste environment, the crowds of people from different worlds together. And he especially liked Prado, he admired him, Prado was the only one that promised to commission him, in this case, a new library for his house in Higienópolis61. He would spend the last few days of his stay, the weekend of the 30th, at Fazenda Sao Martinho. He continued to draw, nature, primitifs and their people. And he would talk with Padro. And Prado would tell him about Brazil, about his Brazil.

Right after his return to Sao Paulo, on 2 December, he immediately left to Rio de Janeiro. And “Rio était le haut et ce haut était couronné comme un feu d’artifice”62, as he mentioned on the first page of “Précisions”. A conclusion. The trip would only be six days long but really intense and Le Corbusier was in awe. Through Prado, Le Corbusier would be welcome and guided by Prado’s relative, Antônio Prado Júnior (1880-1955), the mayor of the city, who placed Le Corbusier at Hotel Glória with a view of Pão de Açúcar and near the beach:

“je suis accueilli les bras ouverts, je suis heureux, je suis en auto, en canot-moteur, en avion; je nage devant mon hôtel (…); je déambule à pied la nuit; j’ai des amis à chaque minute de la journée, jusque presque au soleil levant; à sept heure du matin, je suis dans l’eau”63.

In this whirlwind life, he flirted with Josephine, enjoyed the “abundância e volúpia das mulatas nos bordéis (…), olha as moças bonitas que passam ao perambular pela noite boêmia nas ruas “destinadas aos marinheiros”, ouve o samba no pé dos morros, cheira o aroma da brisa”64 of the sea. He visited Town Hall, connected with the local elite, including José Graça Aranha (1868-1931) – who was part of the group that included Eça and Eduardo Prado – or Manuel Bandeira (1886-1968), and reunited with Tarsila. And he roamed the city, observed it from up close. He talked about the people, he talked about the black people “beaux et magnifiques”65 and about “masques indiens du musée du Rio”66. He went up the mountains, walked through the favelas and saw the landscape down to the sea. He visited Paquetá island, in the Guanabara Bay, and saw the landscape from the perspective of the sea. He flew once more and saw the landscape from above “sur toutes les baies, (…) contourné tous les pics, (…) on est entré dans l’intimité de la ville, (…) tous les secrets qu’elle cachait, (…) on a tout vu, tout compris”67. And he drew compulsively, he wanted to understand Rio de Janeiro: “sur l’avion, j’ai pris mon carnet de dessin, j’ai dessiné au fur et à mesure que tout me devenait clair”68. He was welcome by Adolfo Morales de los Rios Filho (1887-1973), president of the Instituto Central de Arquitetos, gave two (paid) lectures at Escola Nacional de Belas Artes in Avenida Rio Branco, on the 5th and the 8th of December, the first one on architecture and the second one, on the eve of his departure to France, on urban planning, in which he presented a very bold suggestion to the city’s urban planning. This would the core topic of “Corollaire Brésilien”, Le Corbusier having dedicated eight of the fifteen pages of the text to Rio de Janeiro69. He spent such exciting and unforgettable days there that they would be the topic of his most passionate prose:

“Quand tout est une fête, quand après deux mois et demi de contrainte et de repliement, tout éclate en fête; quand l’été tropical fait jaillir des verdures au bord des eaux bleues, tout autour des rocs roses; quand on est à Rio-de-janeiro”70.

Thus started the corollary, echoing the émerveillement as a challenging and inspiring mise-en-scène. It was challenging because it did not embrace any of his previous urban projects and inspiring because it called on reflection and promoted action. If “Précisions” is a theoretical summary, “Corollaire Brésilien” is both a conclusion and the beginning of a new path that the suggestion for the urban planning of Rio de Janeiro gives origin: “ce corollaire commente un état de tension naissante en ces lieux de croissance précipitée: l’urbanisme”71. The new era announced in the last page of Précisions”, on “Grands Travaux”72, translated as theory – transmuted in puriste – would be later be placed in practice in “La Ville Radiueuse” (1935). Le Corbusier was perfectly aware that there was something new, something he saw himself discovering, which was why he said that “après deux mois et demi de contrainte et de repliement, tout éclate en fête”. There is a before and an after Brazil.

You may wonder: and what has Portugal to do with all of this? Probably nothing. But the challenge and the inspiration that Rio de Janeiro would require that Le Corbusier analysed the city in close detail:

“Les rues de la ville s’en vont vers l’intérieur, dans les estuaires de terre plate entre les montagnes tombant des hauts plateaux ; les hauts plateaux seraient comme le dos d’une main s’écrasant grande ouverte, au bord de la mer ; les montagnes qui descendent sont les doigts de la main ; ils touchent à la mer; entre les doigts des montagnes, il y a les estuaires de terre, et la ville est dedans; une ville gaie, portugaise, charmante”73.

The joyful, charming, and Portuguese city that, Le Corbusier suggested should be preserved, unlike what was expected. The city translated into orographic organization, in line with the coast, that dives into the valleys and climbs the hills and is open to the sea. And the sea of Rio de Janeiro “est une carte de géographie du temps de la conquête, avec les golfes, les montagnes, les navires”74. You could say that Rio de Jaeiro is the sublime manifestation of Lisbon.

Yet, there is a less obvious side. Though Le Corbusier’s (still Jeanneret) vision of Brazil is linked to his training and to his library75, the vision he has of Brazil in “Précisions” coincides with Prado’s, as well as Cendrars’s, a Portuguese-Brazilian perspective. It is the vision of paradise by Vaz de Caminha of, the eulogy to nature, geography, river, and land paths, but also that of European emancipation and a modernity that is both Portuguese and Brazilian. All these visions are in the book. The admiration for the Portuguese or Brazilian-Portuguese discoverers and colonizers, “on les voit un peu comme des dieux: n’est-ce pas, Homère?”76, “quel courage, quelle initiative, quelle persévérance!”77, “un puissant levier de stimulation malgré même ses horreurs, ses massacres inexorables, ses destructions décrétées au nom de Dieu”78, personifying it in “J’ai tenté la conquête de l’Amérique par une raison implacable et par une grande tendresse”79. Or in the émerveillement before the landscape vierge et verte, primitif, in awe of the “ao esplendor, à força e ao mistério da natureza brasileira” where, like Caminha, “percebe-se o encantamento do maravilhoso achado que surgia diante dos navegantes depois da longa e incerta travessia”. It is a vision of paradise, and, because it was unexpected, we may already anticipate how intense the flight to Assunção would be

“le fleuve Paraguay qui est ici à la fin de sa course, à son confluent avec le Parana, et qui remonte indéfiniment vers le nord, dans le forêt vierge du Brésil, jusque tout près de l’Amazone. Le cours de ces fleuves, dans ces terres illimitées et plates, développe paisiblement l’implacable conséquence de la physique; c’est la loi de la ligne de plus grande pente et puis, si tout est devenu plat, c’est le théorème émouvant du méandre. (…) J’ai baptisé ce phénomène, la loi du méandre”80

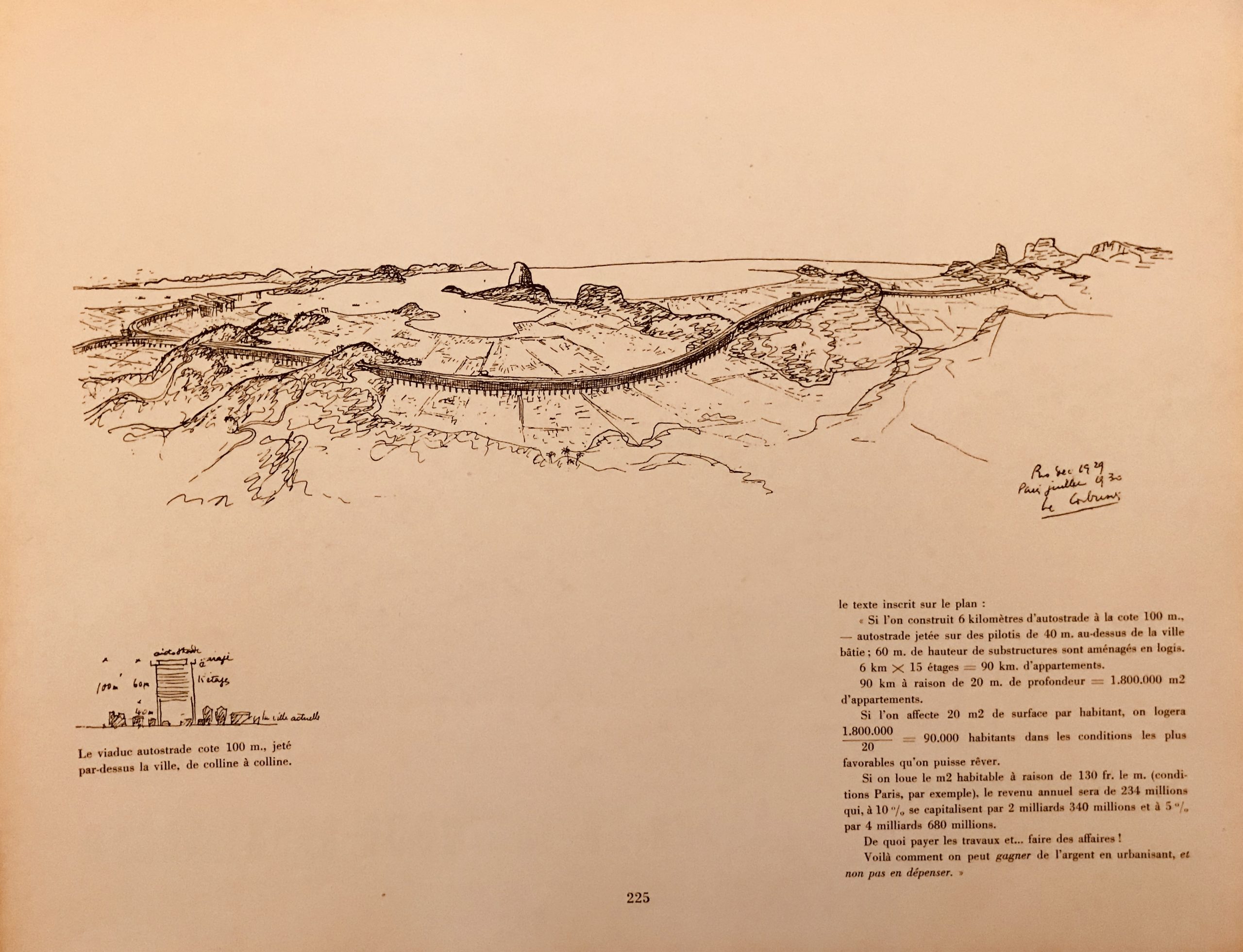

Which will be confirmed in the vol d’oiseau over Sao Paulo and, especially, over Rio de Janeiro. In fact, in his Brazilian lectures, he would mention the loi du meandre, “ce miraculeux symbole pour introduire mes propositions de reformes urbaines ou architecturales”81, negating the logic of (his) Brazill, where “les estuaires de terre plate entre les montagnes tombant des hauts plateaux; les hauts plateaux seraient comme le dos d’une main s’écrasant grande ouverte, au bord de la mer ; les montagnes qui descendent sont les doigts de la main ; ils touchent à la mer ; entre les doigts des montagnes, il y a les estuaires de terre, et la ville est dedans”82, onde “Le site entier se mettait à parler, sur eau, sur terre et dans l’air”83, onde “il y a des origines lointaines à ces routes qui viennent se nouer en ville”84. Nature, geography and land and river paths are used to reiterate the core argument in Caminhos Antigos e Povoamento do Brasil and in other Brazilian colonial historiography, in fact, at the basis of Le Corbusier’s urban suggestions for Rio de Janeiro, as the long viaducts proposed are “paths”, which, in the case of Rio de Janeiro and its many curves and slopes, recalls the contemporary coffee plantation system, now in a machiniste version.

As Prado, Le Corbusier urged Brazil to create its own destiny in “Précisions, its emancipation: “Votre destin est d’agir maintenant”85. There were some nuances to this, though. Le Corbusier liked the exotic “coisa exótica que vemos pelas ruas”86 and, like Cendrars, he rejected the “três raças tristes” as an obstacle to the future of the modern and the Brazilian. In this context, he likes the “cannibalism”87 of the young people of Sao Paulo while in “communion avec les forces les meilleures”88, as a mixing of “chair même de ses propres ancêtres”89, while “adhésion aux principes heroïques dont le souvenir est encore présent”90, including Portuguese heritage, and stated that “un tel sursaut de courage n’est pas inutile là-bas”91. However, he did not completely agree with it, nor was the emancipation towards Europe (discussed in “Précisions”) complete.

It merely concerned abandoning historicism, academia and urban theory of the Societé Française des Urbanistes and of everything he considered obsolete, because Paris remained “le lieu des championnats ou des gladiateurs (…) qui établit le dogme du moment. Paris est un sélectionneur”92. This means that Paris was key to the new Brazil, i.e., Le Corbusier consideeds himself key to Brazil, he wanted to resolve “les scrupules, les doutes, les hésitations et les raisons qui motivent l’état actuel” and thus “l’architecture naitra”93.

|

Moreover, there was no complete emancipation of Brazil regarding the Portuguese or the Portuguese-Brazilian legacy. Le Corbusier did not really placeBrésil – vieux Portugal94 and new Brazil in opposite corners, because the former had “un puissant levier de stimulation”. In fact, one of the triggers for the modern and the Brazilian would soon be a reality through the architecture theory of Lucio Costa95. Le Corbusier describeed the discoverers and the pioneers as Greek heroes – “on les voit un peu comme des dieux: n’est-ce pas, Homère?” – who, like Ulysses, were at the root of a culture. This was the world of the “jeu savant, correct et magnifique des volumes assemblés dans la lumière”96, of esprit grec and of grâce latine. To Le Corbusier, Brésil – vieux Portugal re-emerged in the modern and Brazilian future, because of its Mediterranean and Latin heritage. In this sense, Portugal was present in the final words of “Corollaire Brésilien” and is present the final words of this paper. |

“vous êtes, en Amérique du Sud, dans un pays vieux et jeune; vous êtes des jeunes peuples et vos races sont vieilles. Votre destin est d’agir maintenant. Agirez-vous sous le signe despotiquement sombre du hard-labour? Non, je le souhaite, vous agirez en Latins qui savent ordonner, ordonnancer, apprécier, mesurer, juger et sourire”97.

Bibliography

ALEM, Branca – As Amizades Brasileiras de Blaise Cendrars: uma análise da Feuilles de Route [policopied text]. Belo Horizonte: Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Faculdade de Letras, 2011. Dissertação do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Estudos Literários.

ALESSANDRO, Stephanie; PÉREZ ORAMAS, Luis – Tarsila do Amaral: inventing Modern Art in Brazil. Chicago: Art Instituto of Chicago, 2017. ISBN: 978-0-300-22861-8.

AMARAL, Aracy – Textos do Trópico de Capricórnio (amigos e ensaios 1980-2005), Volume 01. São Paulo: Editora 34, 2009. ISBN: 978-85-7326-364-0.

AMARAL, Aracy (org.) – Tarsila Cronista. São Paulo: Universidade de São Paulo, 2001. ISBN: 978-85-3140-607-2.

BAUDOUÏ, Remi; DERCELLES, Arnaud (org.) – Le Corbusier correspondance, Lettres à la famille 1926-1946. Gollion: Infolio, 2013. ISBN: 978-2-88474-259-7.

BERRIEL, Carlos – Tietê, Tejo, Sena: a Obra de Paulo Prado [policopied text]. Campinas: Universidade Estadual de Campinas, 1994. Dissertação de Doutoramento (PhD Thesis).

CENDRARS, Blaise – Poésies Complètes. Paris: Denöel, 2005 [1947]. ISBN: 2-20725-271-X.

COSTA, Lucio – Registro de uma vivência, 3rd edition reviewed. São Paulo: SESC and editora 34, 2018 [1995]. ISBN: 978-85-7326-720-4.

EULALIO, Alexandre (org.) – A Aventura Brasileira de Blaise Cendrars, 2nd edition reviewed and extended. São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 2001. ISBN: 978-85- 31405-53-2.

FRANCHETTI, Paulo – Estudos de Literatura Brasileira e Portuguesa. São Paulo: Ateliê Editorial, 2007. ISBN: 978-85-74803-53-1.

GUERRA, Abilio – O primitivismo em Mário de Andrade, Oswald de Andrade e Raul Bopp. Origem e conformação no universo intelectual brasileiro. São Paulo: Romano Guerra, 2010. ISBN: 978-85-88585-24-9.

HARRIS, Elizabeth Davis – Le Corbusier – Riscos Brasileiros. São Paulo: Nobel, 1987. ISBN: 978-85-21304-69-2.

LAHUERTA, Juan José – Le Corbusier e la Spagna, con la riproduzione dei carnets Barcelone e C10 di Le Corbusier. Milan: Electa, 2006. ISBN: 88-370-4140-3.

LE CORBUSIER – Carnets, Volume 1, 1914-1948. Paris: Herscher, Dessaine et Tolra, 1981. LE CORBUSIER – Une maison, un palais. Paris: Connivences, 1989 [1928]. ISBN: 2-86649-016-9.

LE CORBUSIER – Précisions sur un état présent de l’architecture et de l’urbanisme. Paris: Altamira, 1994 [1930]. ISBN: 2-909893-06-5.

LE CORBUSIER – Vers une architecture. Paris: Flammarion, 1995 [1923]. ISBN: 978-2-8012-1744-7.

LE CORBUSIER – La Ville radieuse. Boulogne-sur-Seine: Éditions de l’Architecture d’aujourd’hui, 1935.

LE CORBUSIER; JEANNERET, Pierre – Oeuvre Complète 1929-1934, 15th edition. Basel, Boston, Berlin: Birkhäuser, 2006 [1934]. ISBN: 978-3-7643-5504-3.

LE CORBUSIER-SAUGNIER – Trois rappels á MM. LES ARCHITECTES. L’Esprit Nouveau, no 01. October 1920. p. 91-96.

LUCAN, Jacques (dir.) – Le Corbusier, une encyclopédie. Paris: Centre George Pompidou, 1987. ISBN: 2-85850-398-2.

MARTINS, Carlos – Uma Leitura Crítica, in Le Corbusier, Precisões sobre um estado presente da arquitetura e do urbanismo. São Paulo: Cosac & Naify, 2004 [1930]. ISBN: 85-7503-290-9. p.265-287.

NOBRE, Ana Luiza (org.) – Lucio Costa. Rio de Janeiro: Azougue Editorial, 2010. ISBN: 978-85-79200-32-8.

PEREIRA, Margareth da Silva – Le Corbusier au Brésil ou les expériences romantiques de la nature, in Paquot, Thierry; Gras, Pierre (coord.) – Le Corbusier voyager. Paris: L’Harmattan, 2008. ISBN: 978-2-296-05238-3. p.105-123.

PRADO, Paulo – Retrato do Brasil, Ensaio sobre a tristeza brasileira, 10th edition. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 2012 [1928]. ISBN: 978-85-35920-22-2.

RODEIA, João Belo – Ventos de Espanha e Le Corbusier: José de Almada Negreiros em Madrid e as visitas de Jorge Segurado e de Carlos Ramos [policopied text]. Lisboa: Instituto Superior Técnico, 2017. Dissertação da Unidade curricular de Cultura Arquitetónica, Programa Doutoral em Arquitetura.

SANTOS, Cecília Rodrigues dos; PEREIRA, Margareth da Silva; PEREIRA, Romão da Silva; SILVA, Vasco Caldeira da – Le Corbusier e o Brasil. São Paulo: Tessela/ Projeto Editora, 1987.

SANTOS, Daniela Ortiz; MAGALHÃES, Mário Luís – Le Corbusier voyager – arquivos de uma experiência arquitetônica. Interdisciplinaridade e experiências em documentação e preservação do patrimônio recente. Atas do 9o Seminário Docomomo Brasil. Brasília: Docomomo Brasil, 2011. [23 June 2020]. Available at https://docomomo.org.br/wp- content/uploads/2016/01/161_M24_RM-LeCorbusiervoyageur-ART_daniela_santos.pdf.

SANTOS, Rui Afonso – O Primeiro e o Segundo Modernismos, in Lapa, Pedro; Tavares, Emilia (coord.) – Arte Portuguesa do Século XX – 1910-1960. Lisboa: MNAC, 2011. ISBN: 978- 989-660-080-8. p. XXVII-XXXVI.

SILVA, Bárbara – Brasil, La reinvención de la Modernidad. Le Corbusier, Lucio Costa, Oscar Niemeyer [policopied text]. Madrid: Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, 2015. Dissertação de Doutoramento (PhD Thesis).

TSIOMIS, Yannis (org.) – Conférences de Rio, Le Corbusier au Brésil – 1936. Paris: Flammarion, 2006. ISBN: 978-2-0891-1610-8. ISBN: 978-2-0801-1610-9.

WALDMAN, Thaís Chang – Espaços de Paulo Prado: tradição e modernismo. Revue Artelogie, Dossier thématique: Brésil, questions sur le modernisme, no 01. 2011. [23 June 2020]. Available at http://cral.in2p3.fr/artelogie/spip.php?article66.

WEBER, Nicholas Fox – Le Corbusier (A Life). New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008. ISBN: 978-0-375-41043-7.

ZAKIA, Silvia Palazzi – Primeira visita de Le Corbusier ao Brasil em 1929. Uma chegada acidentadíssima!. Vitruvius, year 09. September 2015. [23 June 2020]. Available at https://www.vitruvius.com.br/revistas/read/arquiteturismo/09.102/5685.