Eren Gazioglu

(UAL) – eren.g94@gmail.com

To cite this article: GAZIOGLU, Eren – Politics and architecture in Turkey (1923 – 1960). Estudo Prévio 11. Lisboa: CEACT/UAL – Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa, 2017. ISSN: 2182-4339 [disponível em: www.estudoprevio.net]

Abstract

To objectively evaluate the manifestation of any kind of architecture in history, the necessity to consider context (as in politics, economy, and geography) is nowadays beyond question — in particular as regards the XX century, in which debates on expression and form in art and architecture were related ever more directly to political agendas. In addition, when it comes to certain countries that are often left out of mainstream textbooks on architectural history, the background of most readers tends to prove insufficient —if not misleading— in complementing the written accounts with pre-conceived general knowledge. Taking these in consideration, the main motivation behind the thesis in question was to create an account on the modern architectural heritage of the Republic of Turkey that would interweave architecture and politics in a way that wouldn’t leave the reader in the dark regarding contextual connections: natural and immediate for the author and for locals, but a mystery for anybody who’s new to the subject.

In the particular case of Turkey, modernity began to manifest itself in the aftermath of the War of Independence (1919-1923) that put an end to the Ottoman Empire and founded the Republic on Turkey on secular grounds. While it was a colossal effort to rebuild a nation from the ground up, the circumstances of the post-war world and the approach of the WWII made it so that 27 years of single-party rule would follow, bringing about an ever-intensifying nationalist agenda as Turkey remained non-belligerent during WWII. It was to end de jure only when the republican party in power lost in the elections of 1950, after which the economic policies of Turkey took a sharp turn towards liberalism. 10 years later, in 1960, a military coup turned the tables once again; Behruz Çinici (1932-2011), polemical yet influential architect from Istanbul, begins his professional life in such a moment. Throughout all these historical events (and other minor ones), architecture took a path as bumpy as that of politics, and this paper aims to address that complexity through a selection of major determinant events and dynamics, without taking any information for granted; and it does so by considering Behruz Çinici as a pivotal point between the “yesterday” and the “today” of the architecture of Turkey.

In conclusion, this paper begins with a simplified historical and architectural version starting from 1923, and gradually —and naturally— intensifies in detail until 1960, the year of the first military coup in Turkey. At that point, it takes a step back to introduce the figure of Behruz Çinici, including his educational and cultural background: his life is analyzed by a subdivision in decades, as the architect himself suggested in various occasions.

Keywords:Architecture, Politics, History, Turkey, Çinici

Introduction

The Republic of Turkey as we know it today has been founded in October 29, 1923 following the War of Independence (1919 – 1922) after the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in the First World War. The newborn republic led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk has been founded on secular and western-oriented ideals, and has undergone an intensive period of reforms in the decades that followed.

Fig.01

Fig.02

Throughout the history of the Republic, modern Turkish architecture has followed a course that had remarkable parallelisms with the political and economic situation of its state. Towards the end of the XIX century, before a genuinely national architectural style began to emerge, the prominent tendency was of eclectic stamp, mainly led by European architects (such as Raimondo D’Aronco and Aléxandre Vallaury, to name but two). (fig. 01, fig. 02) This western-oriented architecture orchestrated by foreign figures was a mirror image of the declining state of the late Ottoman Empire which sought to extend its lifetime through reforms following European models. Discontent of Turkish intellectuals against foreign dominance inspired a generation of Turkish artists and architects: it sparked nationalist debates and eventually helped shape what is known today as the First National Architecture Movement. (fig. 03)

Fig.03

Although a detailed analysis of the history of the War of Independence is beyond the scope of this paper, the toll it had on the economic and demographic panorama of Turkey is still worth noting for its relevance regarding the course of Turkish architecture. An all-or-nothing push to overthrow the occidental invasion of the already exhausted remnants of the Ottoman Empire left the Republic of Turkey empty-handed to rebuild the nation, not to mention the debts inherited from the fallen empire. Economically, the goals were in continuity with those in the late Ottoman empire: a relatively liberal approach for the “raising” of a local bourgeois as a mechanism for growth and development in modern character. Foreign investment was welcome only with careful measures against their capitalizing effect, encouraging the local entrepreneurs to collaborate with foreign companies, and notable progress was made regarding industry and agriculture. However, such early vision was replaced gradually by statist and protectionist policies as the Second World War drew closer, the consequences of which will be discussed later in this paper.

As the will to dissociate formally from Ottoman roots and to keep up with Western civilizations gradually settled, the main motive that characterized the first years of the republic became the creation a new national identity. To this end, a vast number of European architects have been officially invited to Ankara, the new capital that was intended to be the symbol of a new, modern, secular Turkey. While the First National Architecture Movement practiced in the Ottoman Empire remained the predominant style in this first period, starting from the year 1927 this search for identity finally started to assume the shape of a slightly modified interpretation of the so-called International Style: it favored representative quality over functionality, therefore suggesting a rather classicized, monumental approach. Even though it was named Yeni Mimarlık (which translates into New Architecture), this movement bore hardly any avant-garde characteristic, as it still relied on formula like symmetry and order, and on traditional elements like vertical windows and stone cladding. It was rather the rejection of eclectic tendencies, the simplification of form, and the application of a more universal architectural language (Sözen & Tapan, 1972). Such inclination is clearly seen in the Ministry of Health (1926-7) designed by Theodor Jost, in the ministry buildings of “Viennese Cubic” style of Clemenz Holzmeister, and in the work of Ernst Egli. (fig. 04, fig. 05)

Fig.04

Fig.05

During the WWII, Turkey’s wisely conducted non-belligerent state kept it from laying waste to what it had achieved through countless difficulties; however, the economic and political conditions generated by war made it so that the policies of the government would start hardening into a more protectionist, statist rule. It followed that the state-sponsored architecture began to shift in a direction similar to what could be observed in Italy and Germany in that period. Aptullah Ziya, a Turkish intellectual, stated in 1933:

Today in Italy, […] a new art is born and is marching with giant steps in the hands of the young Italian artists encouraged by their government. The Italians have created a Fascist architecture. The Turkish nation has carried out a revolution that is far greater than what the Fascist Rome calls a revolution. However, it lacks a feature. This revolution hasn’t been monumentalized.

ZİYA, Aptullah. (1933, September-October). İnkılap ve San’at. Mimar, 33-34, 317

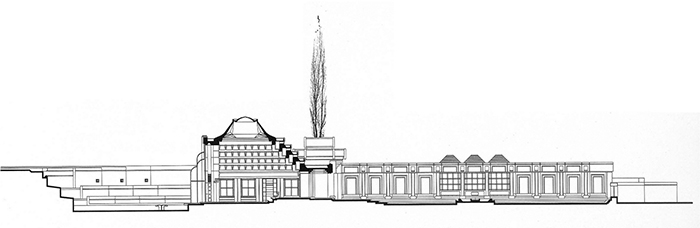

While the invasion of Austria in 1938 and the consequent arrival of Clemens Holzmeister are two linked events that are fairly easy to read, the coincidence of this statement of Aptullah Ziya with the rise to power of the nationalist party in Germany in 1933 is much more subtle and curious, but essential in understanding the dynamics of the period. So is the chain of events from the construction of the Exhibition Hall in Ankara designed by Turkish architect Şevki Balmumcu in 1933, to the arrival of Paul Bonatz in Turkey, and the conversion of the Exhibition Hall into a State Opera Building, to which we will come back to shortly in order to underline how it has been a recurring (and still present) dynamic that Turkey often chose to erase its collective memory.

The foreign architects called by the government were in fact playing a dual role: the definition of the esthetic canons of the new Turkish architecture through the official, state-sponsored buildings they built, and the raising of a generation of Turkish architects in the universities where they taught, and in some cases, which they reformed. It is a period of several contradictions. The students had a huge respect towards their German and Austrian masters, but were slowly growing tired and discontent of them securing all large-scale commissions; with the rigid, nationalist aura of the ‘30s, official buildings became increasingly classicized, monumental symbols of power, but championed not by Turkish architects but by the German-speaking.

Amidst the domination of the architectural context by foreign architects, one early exception has been the project of Şevki Balmumcu for an Exhibition Hall in Ankara, which shared the first prize with the project of Paolo Vietti Violi as early as 1933 (Akcan & Bozdoğan, 1972). When the latter proved to be too expensive to be realized, it was decided that Balmumcu’s design would be built. This project was clearly distinct from the majority of the projects commissioned by the state, being closer in form and in approach to the European modernism, and to the aesthetics of Art Déco: although it is unclear whether it was intentional or not, the composition of curved volumes and naval elements could be read as parallel to the Streamline Moderne tendencies in Europe and in North America. (fig. 06, fig. 07)

Fig.06

Fig.07

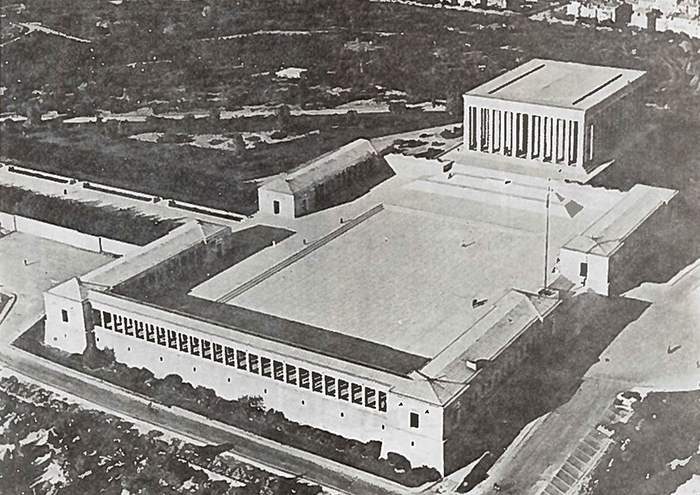

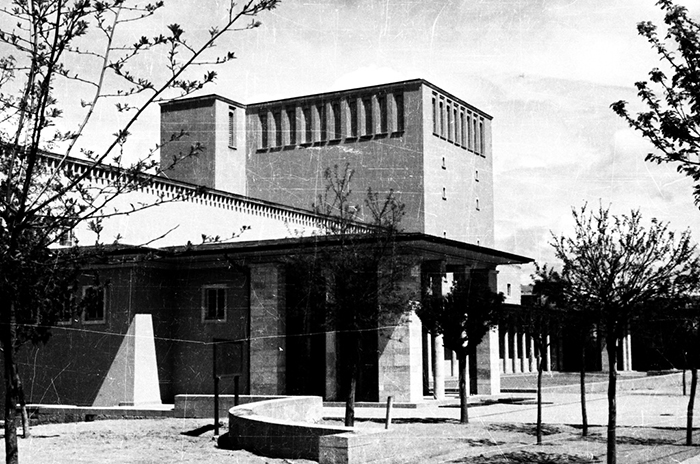

However, when Turkish architects really began to receive relevant works from the state –that is, towards the beginning of the ‘40s– the dominant tendency was already of a classicized and monumentalized stamp, as mentioned above. Turkish architects such as Emin Onat (1908-1961) and Sedad Hakkı Eldem (1908-1988) accepted the “Viennese Cubic” tradition introduced by their German-speaking masters and pioneered its development into a Turkish style further in the monumental direction, as approved and promoted also by Bonatz. An early example of this style, named the Second National Architecture Movement, is the Ankara Railway Station (1935-7) by Şekip Akalın –dwarfed nowadays by the monstrous new train station opened in October 2016– (fig. 08, fig. 09), followed by the Ministry of Transportation (1938-41) by Bedri Uçar, “the most beautiful building in Ankara” from the point of view of Bonatz (Sözen, 1984). This style later found its highest expression in works like Anıtkabir (the mausoleum of Atatürk, by E. Onat and O. Arda, 1942-53) and the Faculty of Literature and Sciences in Istanbul (E. Onat and S. H. Eldem, 1944). (fig. 10, fig. 11) It was in this period that Bonatz carried out the conversion of the Exhibition Hall of Balmumcu, into a State Opera (1946-8): a landmark event in which Bonatz demolished and modified the original design to fit his aesthetic view, introducing a concept very familiar nowadays– that of erasing pieces of collective history to tailor it to fit current needs. (fig. 12)

Fig.08

Fig.09

Fig.10

Fig.11

Fig.12

Coming back to the affinity between politics and architecture, it’s essential to consider both the hardening political and economic structure and the concentration of works in Ankara in parallel with the architecture that was being promoted in the ‘40s. Only after the end of WWII and the concurrent decline of popularity of the Republican People’s Party –the single party in power since the foundation of the republic– would the existing dogma in architecture be put into question, in virtue of Turkish architects gaining more and more prestige; not to mention the dissolution of the nationalist aura that was brought about by the WWII, after which the demonstration of power through architecture was no longer of any practical use. The same architects that contributed to the Second National Architecture Movement promoted this new, more liberal architecture; instead of projecting national pride onto the façades of the buildings, it became more of a matter of taking pride in competent local architects and innovative architecture that managed to stand up to the rest of the world. A first step toward a detachment from the recent past to catch up with the international setting was the Palace of Justice in Istanbul (E. Onat and S. H. Eldem, 1949); soon after, the Republican People’s Party was to lose for the first time in the 1950 elections, bringing the liberal Democrat Party to power, and Istanbul was to become the new focus of architectural and urban interventions.

Fig.13

The brief “economic miracle” carried out by the liberal policies of the new government had an instant response in terms of architecture, bringing about one of the biggest paradigmatic shifts in the history of Turkish architecture: the Hilton Hotel in Istanbul (Skidmore, Owings & Merill, in collaboration with S. H. Eldem; 1952-5). (fig. 13) Quickly becoming a symbol for comfort, precision, and progress, this formula –horizontal block of reinforced concrete with a “democratic” honeycomb façade on the two long sides– remained the dominant approach for the rest of the decade, roughly until the coup d’état of 1960. A detailed political account would make us drift off-topic, but it’s worth noting for the sake of continuity that this symbol of “Hiltonism” corresponds also to an alignment with the American soft-power, with its counterparts in international politics being the participation in the Marshall Plan (1948) and in the Korean War (1950-3), the adhesion to NATO (1952), and other minor events. This politically charged architectural enterprise met a proper political ending, leaving its place to a much different array of approaches.

Fig.14

The early ‘50s in Turkey were characterized by a radiant optimism, and rightly so, as the Democrat Party (DP) started off by circulating the capital accumulated in the treasury of the state in the rough years characterized by statist rule, thus creating a brief economic miracle that marked the beginning of a new era; one that would, unfortunately, degenerate into a corrupt government in a flash, triggering in 1960 the first military coup. In these years, DP focused its attention to the long-ignored Istanbul, “re-conquering” it in the words of then prime minister Adnan Menderes, through colossal urban interventions in a neo-Haussmannian perspective —as expected from a highly populist rule— in the historical peninsula of Istanbul that was characterized by a dense urban fabric composed of old wooden buildings built during Ottoman reign. Large parts of said fabric were torn down for large infrastructural connections, while others were demolished to give visibility to built historical heritage, especially mosques and medrese (Ottoman schools), an operation analogous to what had been done in fascist Italy. The building of such infrastructure gave way to an immense industrial growth and consequently to urban sprawl: poor foresight brought with it the squatter settlements called gecekondu and the poor-quality yap-satçı contractor houses, troublesome legacies that continue to date. (fig. 14)

Another important notion introduced in this brief period that left an indelible mark is the alignment with the American soft-power. Along with the end of the war economy, Turkey attempted a new articulation with the global market; these resulted in a growing sympathy towards the United States and its mass consumerist culture. As mentioned above, Turkey was one of the countries that were included in the Marshall Plan of 1948, and for its geopolitical position it was seen as a key ally by the United States for containing the spread of communism. After this tendency found expression in the Hilton Hotel in Istanbul, architecture continued to parallel such language until the 1960 coup, with anonymous white cubes with honeycomb façades dominating the architectural enterprise of those years, no matter what the function of the building.

The background of Behruz Çinici

When it comes to self-assessment, Behruz Çinici is a rare case, and his retrospective claims depict his career often correctly and precisely. For this reason, his life will be analyzed in 10-year divisions at a time, as suggested by the architect in various occasions.

Born in 1932 in Istanbul, he lived in two districts that he always recognized as a source of inspiration in his later work: Kadıköy, situated in the Anatolian part of the city; and Fatih, a relatively conservative district inside the historical center. His first “spatial experiences” consisted of his daily commute from Fatih to his high school in Vefa: he mentioned crossing the mosque Şehzade Camii knee-deep in snow, walking in the “vaulted streets of Yeni Cami” and reaching Fatih following the tram routes, all of which he deemed lost in his interviews (interview in Tanyeli, 1999). In addition, his experience in the high school was also one in which drawing was essential, as they often had history lessons “in the courtyards of mosques with pen and paper in hand” (interview in Tanyeli, 1999), and three-dimensional geometry lessons with intensive drawing.

In his memories, besides the immediate reading of the Ottoman heritage that influenced Turkish architects, it is also possible to notice how the national agenda of reshaping the identity of Turkey through modern architecture initially failed to be understood by the people:

In those years, we didn’t know what was an architect, we didn’t know whether it was a draughtsman or an engineer. I only knew the faculty of construction. We perceived architecture as a school of apprentices that worked under the civil engineer.

Interview in: TANYELİ, Uğur (ed.) (1999) “Improvisation” Mimarlıkta Doğaçlama ve Behruz Çinici. Istanbul: Boyut Yayın Grubu.

While this was true for the people outside the discipline, the same couldn’t be said for the university. When Çinici was enrolled in ITU, the Technical University of Istanbul, it was home to the most important and active architects of the time: Paul Bonatz, Clemens Holzmeister, Gustav Oelsner, and Rudolf Belling are some of the German-speaking visionary professors that have left their mark on Çinici and his colleagues, not to mention other influential Turkish professors such as Emin Onat and Kemali Söylemezoğlu. This is one of the main reasons why Behruz Çinici is taken in this essay as a pivotal figure in the history of architecture in Turkey: he is a successful example of a generation that experienced the teaching of the so-called “German-speaking” first-hand, and that started working as architects after the single-party rule and its architectural vision had already disappeared.

’50 – ’60, first years after the university

Once he was done with the university, it wasn’t difficult for Behruz Çinici to find work, considering the scarcity of architects and the economic boom of the ‘50s discussed above. His acquaintance with Enver Tokay, an assistant at ITU known as “Concours Enver” for his success in architectural competitions, was an important source of inspiration. Together they participated in various competitions, among which the General Directorate of State Hydraulic Works (Ankara, 1958) and the Atatürk University (Erzurum, 1957) are built examples. (fig. 15, 16)

Once he was done with the university, it wasn’t difficult for Behruz Çinici to find work, considering the scarcity of architects and the economic boom of the ‘50s discussed above. His acquaintance with Enver Tokay, an assistant at ITU known as “Concours Enver” for his success in architectural competitions, was an important source of inspiration. Together they participated in various competitions, among which the General Directorate of State Hydraulic Works (Ankara, 1958) and the Atatürk University (Erzurum, 1957) are built examples. (fig. 15, 16)

Fig.15

Fig.16

The General Directorate of State Hydraulic Works shows an early separation from the Hilton model: by that time, that model was already spread nationwide, and its variants already manifested. The social and economic conditions were favorable for new architectural forms to be experimented, and Çinici and Tokay took advantage to apply a relatively innovative solution instead of “tropicalizing” elements of European modernism, by applying a curtain wall façade system (Bozdoğan & Akcan, 2012). This way, they also tested the limits of the means that were available; an approach that Çinici will repeat in various cases, particularly in his masterpiece METU.

’60 – ’70, Middle East Technical University

No matter how exceptional the qualities of a successful architect, in most cases part of the success depends also on being in the right place at the right time; this applies also to Behruz Çinici. Besides getting his formation in ITU at a time when the most prominent German-speaking stars of Turkish architecture were teaching, his professional life began contemporaneously with the foundation of the Chamber of Turkish Architects and with the dissolution of the “Hilton effect”.

Fig.17

Fig.18

That being said, in May 27, 1960, a military coup has ended the government of the Democrat Party, a provisionary military regime followed (in which a new constitution has been written) and the democracy has been restored in roughly one year. While debates regarding the political involvement of architects were taking place, a new generation of architects and critics sought alternatives to the rigidly cartesian approach applied to date. In the Sheraton Hotel in Istanbul (1959-73) (fig. 17), the “democratic” Hilton-inspired façade was articulated for the first time in a non-orthogonal direction, creating an organic plasticity evocative of Frank Lloyd Wright; and the project for METU came right after (1961) (fig. 18) as an enormous site for experimental architecture. From METU onward, he collaborated with his wife Altuğ Çinici in all of his projects, aside from other occasional collaborations he did.

Fig.19

The university campus is organized along a central walkway in north-south direction, called allée by its users, and described by the architect as “a thin, long path that connects the architecture faculty to the other parts, permeating also the interior spaces and creating tensions in the balance of the light” (interview in Tanyeli, 1999). (fig. 19) An “ecological spine” that makes use of elements with microclimatic effects, such as water and various plants, in a successful attempt to transform the dry context into a lush environment. On the west side are academic facilities, on the east administrative or social. Another axis joins from the south-east and leads to services: recreational areas, sport facilities, residences, and such. The facilities themselves are among the first examples of fragmented block distribution, a notable earlier example being the Manifaturacılar Market (Doğan Tekeli, Sami Sisa, and Metin Hepgüler, 1959). (fig. 20) By that logic, the functional areas are conceived as free-standing, often rectangular buildings, distributed sequentially according to the program, which are then connected by circulatory elements; this was formulated as a valid alternative to the Hilton block, and soon after, it became a paradigm itself (Bozdoğan & Akcan, 2012). It also does a wonderful job in amplifying the aforementioned microclimatic effect.

Fig.20

Fig.21

As mentioned earlier, Çinici also tested what could be done in terms of technology. The METU campus is the first application of exposed concrete in Turkey; its brutalist lines appeared almost simultaneously with its counterparts in developed countries (Şen, Sarı, Sağsöz & Al, 2014). In addition to this technique, during the development of METU, some elements in concrete have been prefabricated, along with other new technological elements being experimented and produced. Plexiglass, for instance, was used in the roof, and aluminum carpentry was applied, all of which have contributed to the development of various components of industry. (fig. 21)

While the alley creates a sense of continuity throughout the project, each facility has its own character, to the point that the complex could be perceived as if it were designed by multiple architects. Although it is true that the references in the architecture of Çinici are so varied and mixed that, from the final result, it’s often impossible to trace back to the original model; in certain parts of the campus —for instance, the gym of METU— it is possible to identify certain prevalent figures. The structural approach that characterizes the gym is evocative of the work of Nowicki (an architect that Çinici got to know from his colleague Concours Enver), whereas in some other facilities one could sense the influence of Wright or Aalto. On top of that, the residences of the campus with their thick brick walls take hints from the climate and the old regional houses of Ankara.

’70 – ’80, crisis and thematic approach

The ‘70s are considered one of the most traumatic and violent period of the contemporary history of Turkey: aside from the oil crises that struck the economy worldwide, the people of Turkey were divided by the two political views generated by the bipolar dynamics of the Cold War. The government was destabilized, no one party could reach the majority in the assembly, and violent events took place ever more frequently. The military intervened once again in March 12, 1971, issuing a memorandum in an effort to restore order. Clashes between left-wing and right-wing groups intensified, with countless casualties, and an even bloodier coup took place in September 12, 1980. The trauma still has a vivid place on both the collective memory and the institutional organization of Turkey.

The architecture also had its share from these events. Behruz and his wife Altuğ Çinici refer to the difficulties encountered in a constantly impoverishing Turkey in their first autobiographic work:

Our building codes, our socio-economic problems, the difficulties in preparing plans, problems concerning labourers, and our ability to build are very different than the conditions that one would encounter in many other countries, especially in those developed. The capability to build in a country in the effort of industrialization, but lacking a construction industry, is full of complications.

ÇİNİCİ, Altuğ and Behruz. (1975). Altuğ-Behruz Çinici: mimarlık çalışmaları = Architectural works: 1961-70. Ankara: Ajans-Türk Matbaacılık Sanayii.

As with many other architects in Turkey at that time, this was one of the main reasons why almost all the projects designed by Çinici encountered complications in the phase of realization; while some of them were built partially, others weren’t realized at all.

Still, following the introduction of cooperative residence models in the republican period, and that of the leisure culture and American consumerism in the ‘50s, one specific program was proliferating in the ‘70s: summer resorts. With the experience he obtained from METU, Behruz Çinici developed various projects for cooperative summer resorts, the first of them being Artur (Burhaniye, 1969) (fig. 22). In this, he explored themes like modularity and repetition, all while making use of the exposed concrete method he got to experiment in METU; making that project worth considering as a bridge that connects the ‘60s to the ‘70s in the career of Çinici.

Fig.22

The main, most ambitious project in this period of his career is a housing site in Çorum, in the region of Kütahya; and as in the other designs he created in this period, he developed his own themes unlike his “reinterpretations” of the International Style blocks in the facilities of METU. The Binevler Site (1971), 5 km far from the Çorum city center, envisaged the creation of a satellite city of 15.000 habitants, with a regionalist scheme that explored vernacular elements, in order to present a productive yet local ambience for the people of Çorum:

I investigated how a productive city could be planned, living for seven years among its people, researching their socio-economic life. […] How can 1000 housing units generate 17 different industries? The balance between sectors has been one of the major themes for me. To devise a unicum composed of diverse actions, a unicum that would include the human being…

ÇİNİCİ, Altuğ and Behruz. (1975). Altuğ-Behruz Çinici: mimarlık çalışmaları = Architectural works: 1961-70. Ankara: Ajans-Türk Matbaacılık Sanayii.

However, as mentioned above, his explorations on vernacular elements have been so intensely reworked by his conscience that it’s hard —if not impossible— to trace back to the original models. Such was the case also for the summer estates, and for another project he made in Ankara: the Iranian School (1975-80). It’s a textbook case for the way he deals with references: he declared that the dominant figure he sought was that of an eyvan —a typical element of traditional Iranian architecture— in the overhang that functions both as the entry of the building and a place for encounter; yet again, such element is unrecognizable by anyone but the architect himself.

’80 – ’90, improvisations

Fig.23

In 1938, Clemens Holzmeister —German-speaking teacher of Behruz Çinici— designed the TBMM Complex in Ankara, which translates into Grand Assembly of the People of Turkey. (fig. 23) In 1978, his student Çinici was called to make an expansion for the first time:

It was year 1978, so I was chosen as an artist member of the Assembly two years before the 1980 revolution. We were two people; one was Sadun Ersin Hoca, the other was me. Cahit Karakaş was the president of the council. We were dealing with certain arguments, choosing the works of art. […] One evening in ’78, the president of TBMM called me: “There’s the idea of making a mosque here, but before that, the deputies don’t even have a place to hang their coats. We need to create working spaces for the deputies, but we don’t have the money. You work with us as an artist member, what do you think we can do to resolve this issue?”. Then he said, “I chose this area, there’s this possibility, I would like for you to design it”.

[…] I said that my teacher Holzmeister lived in Salzburg. It wasn’t possible for us to add a building without his permission. I proposed: “Let’s invite him here and ask his opinions.” […] In year ’79, he was invited, he was 93 years old. […] He concluded: three different projects would be prepared by three of his students. He asked that these projects would be sent to Salzburg anonymously. […] Our project was chosen.

Interview in: TANYELİ, Uğur (ed.) (1999) “Improvisation” Mimarlıkta Doğaçlama ve Behruz Çinici. Istanbul: Boyut Yayın Grubu.

Fig.24

The project in TBMM was one of the biggest challenges Çinici has confronted in his career: he was called to confront his teacher and his architectural heritage typical of the Second National Architecture Movement. The project area was an extension behind the original assembly, situated in its axis of symmetry; Çinici wanted to create a negative image of the assembly building, with two identical L-shaped buildings placed symmetrically in a way that they would envelop the original volume. (fig. 24) Apart from this configuration, and his respect for not exceeding the height of the original building, the project follows an independent composition: the architect devised a very complex modular scheme that, as in most of the cases, tested the technological limits by employing —for the first time in Turkey— prefabricated, pre-compressed concrete elements. The award-winning building was torn down in September 2016.

After this episode with the Assembly, Behruz Çinici was called twice again: first for the TBMM Deputy Residences (1984), then again for the TBMM Mosque (1987). For the residences, 25 hectares of free area have been allocated for the architect to design 400 housing units. As always, the architect has started by determining certain themes, and investigating traditional residential typology, yet the resulting form doesn’t let for a direct reading of such connection. In his interview with Tanyeli, he defended the reasons behind creating 400 identical units, as well as the decisions he took on a bigger scale:

There’s an order to follow. It must be 135 sqm, it must reference our traditional architectural motives, it must be made with wooden lattices, and so on. […] “Why is it repeated 400 times?” Because there are 400 deputies. And there’s a program to follow. Here the critic doesn’t see the city. Here it’s not only the house that’s made, there are 10 streets. And like in old Turkish villages, there’s a bigger unit that seeks to open up towards a valley. […] It’s an official site being made. A deputy makes 20 kids, could even make 25! It doesn’t fit in 135 sqm. What can the architect do about it?

[…] I don’t consider 400 deputies one by one, I can’t. But anyway, there’s the character of the Turkish house, there’s a tradition. The entrance floor is that of the garden in our tradition. In it there’s a room for guests. Upstairs, the bedrooms… Then there’s the attic, that could host 10 of those 20 children if you wanted.

Interview in: (1991, April). Arredamento Dekorasyon, 25, 69

When it comes to the projects of Çinici, and his way of “digesting” the references to create an independent formal result, his own definition of himself that suggests that he did “improvisations” in architecture —in the musical sense of the term— gives insight to his approach, especially those in this period in question, most importantly in the case of the TBMM Mosque, in which he collaborated with his architect son Can Çinici. “For example, if tonight I played a nihavend scale improvisation with my tambur, now I’d do it in one way, tomorrow in another” (Interview in Arredamento Dekorasyon, 1991).

Fig.25

Fig.26

The TBMM Mosque (fig. 25, 26) is one of the most important religious projects of Turkey and of the Islamic world in general in the XX century, recognized also by the prestigious Aga Khan Award. Named “Square-Prayer-Library Complex” by its architects, it’s situated in the northernmost part of the Grand Assembly, and has been debated quite a lot for symbolic reasons regarding the secular character of the government. The subjective approach of Behruz Çinici, combined with mindful design decisions that addressed the concerns of the Turkish public, made possible a spatial configuration that is secular and traditional in the same time.

The original influence was that of the praying schemes of early Islamic civilizations: that of a linear formation; instead of the central plan with a principal dome, he insisted that the extension of a straight line is more adapted to the Islamic view (Interview in Arredamento Dekorasyon, 1991), as it uniformizes the experience for every faithful instead of creating more “privileged” areas in the center. In other words, instead of a planar configuration —for which a monumental semantic would be necessary—, the architects decided on a linear one, a decision that brought with it more modest proportions. They also eliminated the minaret (tower for the call to prayer) substituting it with a cypress tree, and made the mihrap (element that points to the praying direction) entirely transparent, affording a view of the hidden garden behind, as a symbol for paradise as attributed by many architects and critics (Tanyeli, 1999).

Fig.27

Fig.28

While the ‘80s of Çinici’s career is remembered mostly by the facilities inside the Grand Assembly, his projects weren’t limited only to them; among other projects that he made, the competition for the Marina Hotel in Tripoli (1982) (fig. 27) and the Taksim Square competition (1987) (fig. 28) are notable for their ambitious and “improvisational” character. Marina Hotel, with a configuration reminiscent of a vertebrate, is an example that demonstrates how far the improvisations of Çinici can go, owing partly to the freedom of architectural expression in the post-coup period that the architects of Turkey were enjoying, contemporary to the flourishment of postmodern architecture in the world. The Taksim Square project, gaining the second prize, also bears a postmodern character, and is interesting for the scale of the intervention: in collaboration with his son Can Çinici, they had come up with an ambitious restructuring project in a Turkey where such competitions usually foresaw revisions of chirurgical character.

Conclusion

Having studied as a pupil of the first generation of the visionary —mainly German-speaking— architects that championed the modern architecture of Turkey, and having worked from the ‘50s on, Behruz Çinici has experienced and contributed to the most critical episodes of the contemporary history of architecture in Turkey. His figure as an architect who continuously challenged the status quo, not only makes him an intriguing figure per se, but also interesting on a broader perspective by which we can understand the dynamics of the big picture. He represented a more “instinctive” kind of architecture in the wider spectrum from the ‘60s on, as Doğan Kuban concluded in an article he wrote back in 1991:

For me, Çinici is one of the few architects that continuously think about architecture and possess a considerable imagination. […] Çinici is one of our few that manage to surpass the level of mediocrity. If we put him in comparison with our famous architects; against a [Sedad Hakkı] Eldem and a [Cengiz] Bektaş that do not allow for fantasy, against a [Turgut] Cansever that manages to balance fantasy and reason, against a [Vedat] Dalokay whose pragmatism prevails over his imagination, in my opinion Çinici (along with Çilingiroğlu and Ergün Aksel who never found the possibility to realize their works) is the primary representative of “instinctive” architecture in contemporary Turkish architecture.

KUBAN, Doğan. (1991, April). Behruz Çinici Üzerine Görüşler. Arredamento Dekorasyon, 25, 81.

Bibliografia

GÜREL, Meltem Ö. (ed.) (2016) Mid-Century Modernism in Turkey: Architecture Across Cultures in the 1950s and 1960s. Abingdon: Routledge.

ELMALI ŞEN, Derya; MİDİLLİ SARI, Reyhan; SAĞSÖZ, Ayşe; AL, Selda. (2014). 1960-80 Cumhuriyet Dönemi Türk Mimarlığı. Turkish Studies, 541-556. Retrieved from: http://www.arastirmax.com/ [16-07-2017]

BOZDOĞAN, Sibel; AKCAN, Esra (2012) Turkey (Modern architectures in history). London: Reaktion Books.

ERTUĞRUL, N. İlter. (2011). 1923-2008 Cumhuriyet Tarihi el kitabı. Ankara: ÖDTÜ.

HOLOD, Renata; EVİN, Ahmet; ÖZKAN, Suha (ed.) (2007) Modern Türk Mimarlığı. İstanbul: Mimarlar Odası Yayınları.

TANYELİ, Uğur (ed.) (1999) “Improvisation” Mimarlıkta Doğaçlama ve Behruz Çinici. Istanbul: Boyut Yayın Grubu.

(1991, April). Arredamento Dekorasyon, 25.

AKŞİN, Sina (ed.) (1990) Çağdaş Türkiye 1908-1980 (Türkiye Tarihi 4). Istanbul: Cem Yayınevi.

SÖZEN, Metin. (1984). Cumhuriyet Dönemi Türk Mimarlığı (1923-1983), Istanbul: Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları

ÇİNİCİ, Altuğ and Behruz. (1975). Altuğ-Behruz Çinici: mimarlık çalışmaları = Architectural works: 1961-70. Ankara: Ajans-Türk Matbaacılık Sanayii.

SÖZEN, Metin; TAPAN, Mete. (1973). 50 Yılın Türk Mimarisi. Istanbul: Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları.

Biografia

Eren Gazioglu was born in 1994 in Istanbul, Turkey. After getting French scientific high school education in Istanbul (Lycée Saint Joseph), he went on to study architecture in 2013 in the Polytechnic University of Milan, Italy. Developing his graduation thesis focused on the architectural history of Modern Turkey explained through the figure of Turkish architect Behruz Çinici —in Italian, titled “Architettura in Turchia: Behruz Çinici e il Pluralismo”— he graduated in 2016, achieving the Laurea title (Italian equivalent to Bachelor). Transferring to Portugal right after for the Mestrado course (Portuguese equivalent for Masters), he is currently studying in the Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa, Portugal as of 2016. He’s native in Turkish, fluent in English and Italian, and advanced in Portuguese and French.