Filipa Ramalhete

CEACT/UAL / CICS.Nova, Portugal

Maria Assunção Gato

Instituto Universitário de Lisboa(ISCTE-IUL), Dinâmia’Cet, Portugal

For citation: RAMALHETE, Filipa; GATO, Maria Assunção – Students living abroad: the art of home sharing. Estudo Prévio 8. Lisboa: CEACT/UAL – Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa, 2015. ISSN: 2182-4339 [Disponível em: www.estudoprevio.net]

Abstract

This paper focuses on the students’ experience of home sharing abroad, resulting from exchange programs, especially in what concerns new ways of living, from lifestyle to house rules.

Young people used to share their family homes and lifestyles from the moment they were born until they got married, however, nowadays millions of youngsters share a house or an apartment in a foreign country for a limited period of time.Things have definitely changed, as have the cultural values regarding domestic roles, their virtues and vices, and we are now in presence of new mobility patterns but also of new lifestyles and house rules.

The home sharing experience contains aspects such as the quest for a suitable place to rent, the establishment of house rules, encountering cultural differences, managing conflicts, and, of course, it implies a lot of fun, as partying plays an important role in studying abroad. Domesticity is under discussion and new territories of the public and private realms are explored.

Keywords: home sharing, architecture, home, spatial anthropology

Introduction

Home, as aprimary human shelter, is one of the main expressionsof human culture and a fundamental purpose of architecture. As a structural element of material culture, it has been thesubject of several studies, regarding its social and cultural relationship with each communities’ history and lifestyle.

Studying thehome has been one of the purposes of spatial anthropology. Despite the theoretical, geographic and chronological diversity we may try to systematize some of the most common approaches on this theme. First of all, we may consider studies in understandingthe home in other cultures, different from the one of the researchers’. Here is where we may find some of the classics: Lévi-Strauss’s (1979) study about the Bororo, in Brazilian Amazonia, Marcel Mauss’s (1974) essay on the seasonal variations on Eskimo dwellings and Bourdieu’s (2002) works on the Cabilian house. These texts are usually centered on specific territories and moments, resultingfromanethnographical research in foreign cultures, and analyzing – from an anthropological perspective – the role of space and home in these cultures.

Another line of research isstudyingtherole thathomeplays in the relationship amongspace, social and cultural patterns, and assets within one certain culture, either throughout a certain amount of time – one example is the paper from Löfgren (2003) on the relation of class, culture and family life in Swedeninthe 20th century – or in a certain period – such as Rosselin’s (1999) paper on Parisian halls.

In recent years, contemporary research themes, such as the relation between private and public domains and gender studies are also present in studies focused on the role of home and domestic space, sometimes overlapping the ethnographic or chronological dimensions previously presented. Some examples are the work from Cieraad on the kitchen and domestic efficiency (2010), and on Dutch windows (1999), or the set of studies about the house as ademonstrative space of consumer habits, behaviors and tastes that highlights the privileged relationships established with the material culture (Miller, 2001a, 2001b; Clarke, 2001; Garvey, 2001; Csikszentmihalyi and Rochberg-Halton, 2002).

These studies are based on approaching thehome as a stable place – where people remain for long periods of time -, and as a spatial basis for cultural practices and values which are not only structural for the communities’ social organization, but also for structuring personal identities. From this point of view, house, family and individuals are inseparable and understanding family relationships is of great importance to understanding society. Actually, some studies on home sharing focuses exactly on intergenerational contexts, such as a study in Québec, Canada (Boulianne, 2004).

Nevertheless, with the increasing mobility patterns from the second half of the 20th century and beginning of the 21st, new residential patterns are emerging, followed by new family structures. If, during the 20th century, European urban lifestyle was rooted on the home sharing tradition of family-based pre-industrial living rules (Löfgren, 2003; Cieraad, 1999; 2002) – andeven, in many popular homes, other tenants were present, such as a bachelor who rented a room in a family house – in the second half of the century the patterns changed and the notion of family wasn’tinthesamehome anymore.

These patterns havedefinitely changed, in multiple ways, and are expressed in various phenomena, one of which is home sharing abroad for student exchange programs (Ramalhete, 2014). Young people usedtoshare their family homes and lifestyles from themomenttheywerebornuntil theygotmarried- and often after it – however, nowadaysmillions of youngsters (men and women), often from different origins, rent and share a house or an apartment in a foreign country for a limited period of time. Thingshave definitely changed, as havethe cultural values regarding domestic roles, their virtues and vices. We are now in presence of new mobility patterns but also of new lifestyles and house rules.

Home sharing abroad

Home sharing is a well-known tradition in western countries, particularly in Portugal, where multigenerational families were the rule until the second half of the 20th century – reinforced, especially in working class homes, by relatives who came to live in the city or a tenant who couldn’t afford living alone and paid the family a small rent, helping to support the expenses. Upper class families also had a sharing tradition with servants – even if spatially differentiated inside the house or apartment. However, most of the home sharing tradition was based on more or less lasting family ties. Even tenants and longtime servants, were often considered as “part of the family”.

In this context, young people lived at home (at least) until theygotmarried(and often after that). Students were an exception to this logic. Until the 20th century, the few universities in the countrywereall located in the main cities of Lisbon, Porto and Coimbra. Therefore, university students who had to leave theirfamily homes to study in the city livedin studentresidences or in rented rooms, often in a house where the landlady was a widow with low income. For women, it was essential to maintain certain moral patterns, assuring a familiar atmosphere and some level of social control. Sharing an apartment with university colleagues wasn’t, until recently, a socially accepted option.

From the second half of the 20th century the situation began to change a little. Although residences and rented rooms are still a reality today, it is also common for young students to share rented houses. Part of the trivializationof this new way of domestic living is strongly related with the experience of the growing number of exchange students (under the Erasmus Program, for example) and the home sharing abroad reality. Since its creation in 1987 by the European Community, the Erasmus program has been contributing to increase the mobility between university students, while strengthening the practice of home sharing among many of them.

For the purpose of this study, home sharing abroad is characterized by the co-habitation of a rented house or apartment by young students with no family ties in a foreign country for a relatively short period of time (three months to a year). The home sharing experience comprises aspects such as the quest for a suitable place to rent, the establishment of house rules, encountering cultural differences, dealing with managingconflictsin living areas, one’s property or dividing the shelf space in the refrigerator, finding levels of understanding and compromising(often in more than one language), and, of course, italso implies a lot of fun, as partying plays an important role on the whole studying abroad experience. More or less conscientiously, domesticity is under discussion and new territories of the public and private realms are explored.

Fig. 1 – Sharing Recipes

Fig. 1 – Sharing Recipes

Generally, youngsters leave their family homes(often for the first time) – characterized by lasting family ties, multigenerational occupation (at least two generations) and well defined social roles -, and face a whole new reality of co-existence within a level of supposed equality of domestic roles. The possibility of studying abroad implies, in most cases, an opportunity to achieve not only greater autonomy and independence from the constraints and family rules, but also to build a new self-identity as adults (Holdsworth, 2009). As the rules previously lived in family homes aren’t applicable any longer, there is a need to create a new model for domestic life, with re-defined roles and rules.

Quite often, this opportunity to gain new ways of independence is also associated to new social relations of belonging and boundingwith peer networks that, to a certain extent, replace the family networks while staying abroad.Moreover, these peer networkslargely contribute to Erasmus experience whichcan be translated into acquisition of social and cultural capital, in addition to educational capital.

This paper presents the preliminary results of a case-study focused on Portuguese who studied or had internships abroad and shared homes in several foreign countries – Home sharing abroad: from cultural shock to global citizenship. Most of them had family homes as departing point. The methodology followed was to conduct 20 semi-directed interviews to 10 menand10 women. The results are presently being analyzed and the first conclusions are now presented. These interviews focused on people who shared homes and other situations, whereas university residences or rented roomsweren’t considered.

The purpose of the research is to identify the problems, challenges and solutions of home sharing abroad. The research focuses on domesticity issues, concerning the social and spatial aspects of this new type of experience. Thus, the following pages will bring out some of the aspects that emerge from the ongoing analysis.

Hierarchy and equality

Regarding the house or apartment itself, location seems to be one of the most important aspects, whether if we are speaking of a secure neighborhood in Rio or of a central one in Barcelona. Special architectural aspects, such as a good view or a balcony are strongly appreciated and seem to be the origin of good shared memories and stories that students preserve about the houses in which they have lived.

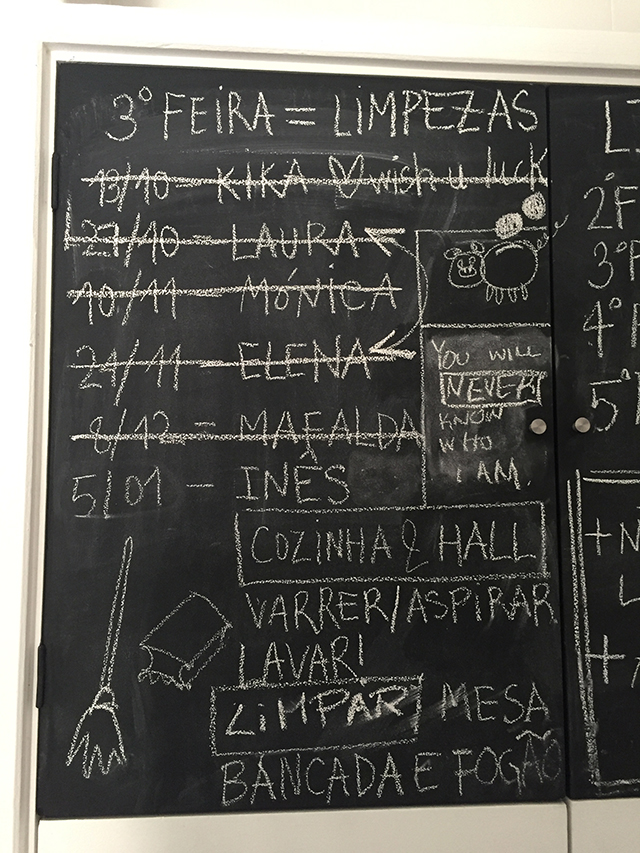

Fig. 2 – House Rules

Fig. 2 – House Rules

Home sharing abroad usually implies a non-hierarchic relationship among the occupants. The age difference is not significant, as they are all young and in their twenties. Gender differences, which may be relevant for other issues, aren’t considered important to establish the home sharing rules and roles. There is, however, a hierarchic value that is relevant – the importance of alreadylivingin the home before. Newcomers have to follow the establishedroutine, either if that implies formal (i.e.cleaning schedule on the kitchen wall) or informal rules such as cleaning up on turns or deciding who performs the various domestic chores. Sometimes, as the interview to JR (female) pointed out, newcomers are subject to an interview with the future home mates, in order to see if he or she has the right profile for living in that specific home.

Gender

As the starting point to home rules is a non-hierarchic one, gender is not described as a differentiation aspect in home sharing. The interviews revealed that – unlike the reality lived in “traditional” rented rooms in Portugal – having men and women sharing the same house or apartment is a common reality and not an obstacle nowadays. When describing the daily chores, all students said there wasn’t any gender difference regarding its attribution. However, some of the female interviewed (ex. JF) reported some gender expectations, when they said that women were sometimes more concerned with tidiness and house hygiene than men. Also in situations where there was room for sharing meals cooked at home, there was a tendency for women to take charge of this task, not so much due to a male incompetence, but more because of a gender effect still relatively rooted in contemporary society. It is a fact that both the functional structure of domestic space as the social roles of gender have changed substantially over time, like Cieerad illustrates concerning the kitchen (2002), notwithstanding the change occurring in the context of these roles being considerably faster than those followed by the home as a physical and functional space.

Common and private domains

One of the most important issues of home sharing is the definition of private and common domains. All interviewees mentioned howimportant their room was asthe most private space in the house. Although significant differences were described – regarding the amount of time spent in the room – most of them can be considered as a portrait of individual personality, and a kind of refuge from whatever happened outside. Personalizing the room seems to be essential for the students to feel “at home”. In fact, the expressive dimension that Miller (2001) assigns to home as privileged place of self-expression and identity construction turns out to be restricted to a single room in a situation of home sharing.

As such, the room iswhere each student makes a material environment that not only representstheir personal and cultural identity, but also representsthe experience that is being lived, either through personal objects that followedthem on the trip, or through new objects collected throughout their stay in the host environment. As the rent usually includes furniture, individual interventions are made through objects, photos or posters, for instance, and often related to each countries’ culture or to trips made by the students.

Like the front door, the doorway can be considered as the symbolic and physical threshold between common and private domain. Several rules or types of behavior are frequently associated with this “line”, such as standing at the doorway (with the body half inside) speaking with the room owner but without entering it without a “formal” invitation. Depending on the degree of intimacy, this limit may be more or less important to the home sharing relationship, but is largely mentioned among students that this was a major difference from their experience back in their parents’ home, showing the existence of new forms of respect, intimacy and relationship with eachone’s private spaces.

Other important aspect is the rules regarding food storage and consumption. In what concerns these aspects the scope of actions is much broader – from identified refrigerator shelving (one for each student) and individual cooking, to sharing shopping and cooking or simply not having food in the house and always eating out.

Fig. 3 -Managing refrigerator shelfs

Fig. 3 -Managing refrigerator shelfs

The common spaces (living room, kitchen, bathroom) also perform an important role in home sharing, since they are the place to hang out either with the co-inhabitants (as said, doing it in each other’s rooms very rare) or with friends who come to visit. In fact, receiving friends (for an evening or for several days) and having parties is a major element to report in the home sharing abroad experience, resulting or in positive memories, or in some kind of conflictthat one does not wish to remember.

Managingconflicts

Sharing home abroad with a friend from the same country is common and easier in some aspects (previous knowledge, same language and similar backgrounds), howeveritdoesn’t avoid punctual conflicts. In this context, managingconflictsis another key element for the home sharing abroad experience. Often dependent on conversations in more than one language (or at least different from the nativelanguage), managingconflictsis strongly related to the existence (or not) of rules.

Fig. 4 – “Remember to store the dishes”

Fig. 4 – “Remember to store the dishes”

When a student shares a home already occupied by other students, there is a set of rules (either written or tacit) that are transmitted to himorher, with the purpose of maintaining harmony and avoiding conflicts. As illustrative example, one of the interviewees (CG, male), described his arrival to a house in Norway, where house assemblies were held periodically, in order to decide domestic issues. Considering this case as exceptional, in general, students’ opinion was that mutual respect and common sense prevailed. Several mentioned that being ashort term experience,it wasn’tworth makingtoo manystrong positions against other peoples’ actions. Nevertheless, some situations were described where someone decided to change home or to stay with friends for a few days (for instance “when there were too many friends staying over and my room was occupied when I arrived from a trip” – JR).

Some conclusive notes

Home sharing abroad is, for Portuguese students, a recent reality, which differs from previous domestic experiences. It represents a modern passage ritual from living with parents, having the “child” role, to a non-hierarchic, more plural situation, where rules have to be defined according to all the co-habitants cultural habits and domestic needs. It is faced as a temporary experience and not asa new way of living, but it leaves marks, as students describe them as life-changing experiences, where lessons of tolerance (andthe limits that they are willing to accept) are learned. Therefore, home sharing not only implies considerable changes to the students’ domesticity patterns, but also involves changes in their identities, as autonomous persons acting on their own in a challenging new environment.

From the spatial anthropology point of view, it is interesting to observe how houses designed for families are adapted to different concepts of common and private spaces and how spatial issues (such as a refrigerator shelf or a doorway) may be essential to define the border between the individual and the collective in each homeOn the one hand, the various public and private spaces that make up the house have new meanings and are being managed and lived according to the user-friendliness of rules negotiated by the group. On the other hand, the personalobjects also havea special meaning when sharing aprivatespace.

In general, we all keep memories and personal stories from the houses we lived in that, somehow, have influenced our values and ways of living the current homes. Notwithstanding that interviewees always thought that this was a transitory experience and that, in a near or distant future, they would go back to a “traditional” family home, it was interesting to observe they also felt at home in their shared homes and classified this experience as being very positive, whether as an opportunity for cultural exchange and social conviviality, and also as an acquired autonomy, personal growth and learning skills. For future work this shall be important to notice how far these new experiences of dwelling have contributed to change the ways of living and perceiving the original homes of these students upon their return, and to what extent it contributed to anticipate their residential autonomy.

(1) We thank Elena Iñoriza and Monica Palfy, both Erasmus students in Portugal, for the photos.

Bibliography

BOULIANNE, Manon – Intergenerational Home Sharing and Secondary Suites. In Québec City Suburbs: Family Projects and Urban Planning Regulations (Research Report). Canada: Université Laval, for Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, February 2004.

BOURDIEU, Pierre – “A casa ou o mundo ao contrário”. In: Esboço de uma Teoria da Prática, Precedido de Três Estudos de Etnologia Cabila. Oeiras: Celta, 2002.

CIERAAD, Irene – “Dutch Windows: Female Virtue and Female Vice”. In CIERAAD, Irene (ed), At home: an anthropology of domestic space. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 1999, p. 31-52.

CIERAAD, Irene – “’Out of my kitchen!’ Architecture, gender and domestic efficiency”. In The Journal of Architecture, 7:3. 2002, 263-279.

CLARKE, Alison. J. – “The aesthetics of social aspiration”. In Miller, Daniel (ed.), Home Possessions: Material Culture Behind Closed Doors. Oxford: Berg, 2001, p. 23-45.

CSIKSZENTMIHALYI, M.; ROCHBERG-HALTON, E. –The Meaning of Things: domestic symbols and the self. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

DOLAN, John A. – “I’ve Always Fancied Owning Me Own Lion: Ideological Motivations in External House Decoration by Recent Homeowners”. In: CIERAAD, Irene (ed), At home: an anthropology of domestic space. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 1999, p. 60-72.

GARVEY, Pauline – “Organized disorder: moving furniture in Norwegian homes”. In Miller, Daniel (ed.), Home Possessions: Material Culture Behind Closed Doors. Oxford: Berg, 2001, p. 60-72.

HOLDSWORTH, Clare – “`Going away to uni’: mobility, modernity, and Independence of English higher education students”. In Environment and Planning, A, vol. 41, 2009, p. 1849-1864.

LÉVI-STRAUSS, Claude – Tristes Trópicos. Lisboa: Edições 70, 1979.

LÖFGREN, Orvar – “The Sweetness of Home”. In LOW, S. & LAWRENCE-ZÚÑIGA, D. (ed.), – The Anthropology of Space and Place: Locating culture. Malden (USA), Oxford (UK), Victoria (Australia): Wiley-Blackell, 2003, p. 149-159.

MAUSS, Marcel – Ensaio sobre as variações sazoneiras das sociedades esquimós. In: Sociologia e Antropologia. S. Paulo: EPU, 1974, v. 2.

MILLER, Daniel – “Behind Closed Doors”. In Miller, Daniel (ed.), Home Possessions: Material Culture Behind Closed Doors. Oxford: Berg, 2001a.

MILLER, Daniel – “Possessions”. In Miller, Daniel (ed.), Home Possessions: Material Culture Behind Closed Doors. Oxford: Berg, 2001b.

RAMALHETE, Filipa – “‘Lá fora’: partilhar casa fora de casa (Homesharing abroad)”. In Pedro Costa, Alessia Allegri (eds.) – Homeland, News from Portugal. Lisboa: Note, 2014, p. 148-149.

ROSSELIN, Céline – “The Ins and Outs of the Hall: A Parisian Example”. In CIERAAD, Irene (ed) – At home: an anthropology of domestic space. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 1999, p. 53-59.

VANDE BERG, Michael; PAIGE, R. Michael; LOU, Kris Hemming – Student Learning Abroad. Stylus Publishing, Virginia, 2012.

Filipa Ramalhete is an anthropologist, with a Masters and a Ph.D. in Territory Planning. She teaches at DA/UAL since 2000 (where she teaches anthropology of the Space, Geography and Territory and Methodology of the Scientific Work) and she is the director of the Architecture Studies Centre, City and Territory of UAL and of the magazine estudoprevio.net. She is also a researcher of e-GEO – Geography Studies Centre and Regional Planning of the Universidade Nova de Lisboa and she lectures Territory Planning and Environment in the Masters in e-Learning in Territory Planning and Geographic Information Systems. Her main research interests are studies of space applied to territory planning highlighting anthropology of the space and spatial justice.

Maria Assunção Gato holds a PhD in Cultural and Social Anthropology. Currently is a Post-Doctoral research fellow by the FCT (financed by national funds of the Ministry of Education and Science) at University Institute of Lisbon (ISCTE-IUL) in the Research Centre on Socioeconomic Change and Territory (DINÂMIA’CET).