José Roberto Ribeiro Rodrigues

rrodrigues.arquitecto@gmail.com

RR Arquitecto – Arquitectura+Planeamento | Assembleia Legislativa da Madeira | Comissão Especializada de Ambiente e Recursos Naturais

To cite this paper: RODRIGUES, José Roberto – Land and urban management of Madeira island: the relevance of Funchal in this process. Estudo Prévio 14. Lisboa: CEACT/UAL – Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa, 2017. ISSN: 2182-4339 [Available at: www.estudoprevio.net]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.26619/2182-4339/14.2

Paper received on 20 September 2018 and accepted for publication on 20 December 2018.

Creative Commons, licença CC BY-4.0: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

This paper discusses the changes derived from several attempts at land management and urbanization of Madeira island since the first settlers, based on map elements that exemplify those important moments in its history.

This allows for understanding the urban changes and their consequences considering Funchal, the first city and the centre of the island, the place where the changes have been most significant and crucial.

Besides this, we will also focus on the regional land management system and its application considering land management in the past decades.

Lastly, we will critically assess all these processes, evidencing shortcomings and possible means of enhancing or overcoming weaknesses that we detected and must be resolved in the near future.

Keywords: Territory, Funchal, Plans, Programs, Occupation, Autonomous Region

Madeira Archipelago

The archipelago of Madeira is in the North Atlantic and has been explored, though not systematically, since the 17th century and was known to those explorers sailing the Atlantic (Carita, 2017).

Its settling therefore marked a first step of a new activity. The first settlers who came to the island to explore the land started a new society here (Carita, 2017).

The archipelago includes two main islands – Madeira and Porto Santo – and two groups of uninhabited islands: Desertas, protected since 1990, are a natural reserve, and Selvagens, which have been submitted for approval as UNESCO World Heritage (ACAPORAMA, 2016).

Madeira island has 758 square kilometres and very diverse landscape, vegetation, micro-climates and traditions. (Adapted from ACAPORAMA, 2016). These landscapes represent an important contribution to tourism, which, currently, is the main economic activity

The archipelago has 801 square kilometres and 267.785 inhabitants. Based on the 2013 population estimates by Direção Regional de Estatística da Madeira (DREM), the population density is 327 inhabitants per square kilometre (ACAPORAMA, 2016). The archipelago’s terrain is also diverse. Madeira island has a very steep topography and the highest peak is Pico Ruivo (1,861m high). Porto Santo island has a very plain topography and a 9 km stretch of golden sand. Desertas have a steep terrain, unlike Selvagens (adapted from ACAPORAMA, 2016).

Image 1 – “Description of Madeira island, the city of Funchal, Villages, Places, Streams, Ports and bays, and other Secrets, made by Pertolomeu Ioão Inginro Della at the time of Governor Bertolomev de Uasconcelos da Cunha, General Captain of this Island in the year of 1654”. Rui Carita – Military Architecture in Madeira, 16th to 19th centuries. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian Lisbon. 1982.

The southern coastline, more sheltered and sunnier, has been considered more productive since early in the settlement. It has a wide, quiet bay, the place where Funchal was founded and rapidly prospered, becoming the centre of the island. Funchal was the ideal place for the early settlers as it was similar to the cities in continental Portugal, which have a lower area where the working classes live and an upper area for its leaders (adapted from Carita, 2017).

The Archipelago of Madeira is an autonomous region of the Portuguese Republic since 1976 and has its own Parliament and Government. The Regional Government is in Funchal. The region is divided into eleven municipalities: Funchal, Câmara de Lobos, Ribeira Brava, Ponta do Sol, Calheta, Porto Moniz, São Vicente, Santana, Machico, Santa Cruz and Porto Santo (adapted from ACAPORAMA, 2016).

The historical heritage: The urban expansion of the island from Funchal:

After the early settlements, around 1425, and by order of king D. João, a village is founded on the eastern area of Funchal bay, which was named Santa Maria or Santa Maria do Calhau (Aragão, 1992). This first urban organization of the island is the origin of what would become the city of Funchal. The village was organized around the small church of Santa Maria and expanded towards calhau. The yard around the church became the social and trade centre. On the side of the church an improvised cemetery was founded, next to it was the public well and from the church and towards the east emerged the first street (adapted from Aragão, 1992).

The village’s image was that of a poor settlement with one-storey houses, most of which made of wood and with thatched roofs. Around 1452, the village of Funchal became a district and, a little later, in 1461, the villages of Câmara de Lobos, Ribeira Brava, Ponta do Sol and Arco had an increasing number of inhabitants. (Adapted from Aragão, 1992).

Funchal had a significant increase in construction between the end of the 15th and the beginning of the 16th centuries and started welcoming people and goods from all over the world (Carita, 2017). As more settlers arrived, there was the need to expand this first population hamlet. New roads were built in Funchal, as well as houses made with wood and thatched roofs, a reflex of the grain production and the many trees surrounding the small roads and alleyways, which enhances this first urban centre where craftsmen settled. At the same time, another hamlet was founded where the future captain lived, in the wooden area of Santa Catarina (Vasconcelos, 2008).

The subsequent land clearing and establishment in a more inland area, up the hill, led to new roads being built, now in the direction of the streams. The three spots where population established were fundamental in the urban structure of the future city of Funchal (adapted from Vasconcelos, 2008).

The hamlet of Santa Maria do Calhau rapidly expanded from east to west and along the coastline and led to the space between the three streams to become occupied. The wealth derived from sugar production allowed for the increase in the number of streets, such as Santa Catarina and Mercadores, allowing the city’s expansion to the west. Around 1470, the Duke D. Fernando ordered that the houses in Mercadores street had tiled roofs and in 1471, the limits of the then village of Funchal became Santa Catarina, São Pedro, Santa Luzia and up to the captain’s house. (Adapted from Vasconcelos, 2008).

Huge equipment was built in Funchal at that time. In fact, in the last decade of the 15th century and the early 16th century, under the supervision of king D. Manuel, several relevant buildings were constructed in the city, which would become a model that would then be applied to the Kingdom, and the old craftsmen borough was refurbished as the village of Funchal became the city of Funchal (adapted from Vasconcelos, 2008).

Image 2 – “Map of Funchal (copy) by Mateus Fernandes around 1570”. António Aragão – O Espírito do Lugar, A Cidade do Funchal. A. Aragão. 1St Edition. Rio de Mouro. 1992.

The urban organization based on the construction of fortifications:

In 1528, after an attack by a ship from Biscay that robbed two ships in Funchal harbour, the king was asked to build a fortification by the population who complained that there was nothing securing the defence of the harbour (Carita, 2017). In 1542, the initial plan was completed to build a bulwark, a tower and walls with two gates, one facing the city and another facing the sea, as indicated by João Cáceres (Carita, 1982).

Following the attack by the pirates in 1566, Mateus Fernandes, wall builder and royal contractor was sent to the island the next year. From that date onwards, several documents evidence how the fortifications were carried out. One of the plans included a large fortress that would expand from Alto da Pena down to the neighbourhood of Santa Maria, which could house all the population of the then city of Funchal (adapted from Carita, 1982).

Image 3 – “Map of the City of Funchal 1567 to 1570, Mateus Fernandes”. Rui Carita – História do Funchal. Associação Académica da Universidade da Madeira. Grafimares, Lda. 2nd Edition. Funchal. 2017.

In 1572, the fortification of Funchal and other areas of Madeira was licensed. This was the first attempt to protect other population areas besides Funchal, as well as of managing the consequences of introducing those military constructions. In Funchal, wall management was established for the sea front and for the areas between the stream of Nossa Senhora do Calhau (currently, ribeira de João Gomes) and the stream of Ribeira Grande (currently ribeira de São João), following their flow and ending in the peaks of Pena and Frias (currently São João). It also specifies the construction of the office in Largo do Pelourinho, as well as the repairs to be made to the fortress, essentially repairing the area today facing Avenida do Mar and the construction of three bulwarks, one facing Avenida do Mar and where the Palace is located today and the other two at each extremity, facing the city. After specifying the number of doors the wall should have, the king ordered the fortification of the other harbours in the city of Funchal up to Machico. In 1614, the city of Funchal expanded beyond the limits of the plan, which forced the launching of a new walls to the east, an area of the borough that would be named São Tiago (adapted from Carita, 1982).

There is not much more information on the fortification of the island. In 1632 there were 9 more fortifications, besides those in Funchal, there were fortifications in Câmara de Lobos, Machico and Calheta (adapted from Carita, 1982).

Image 4 – “Reconstitution of the city wall and its fortifications at the end of the 18th century on a current map of the city of Funchal (2013). Thirteen of the sixteen gates of the city are shown. Collection António Aragão, ARM”. Rui Carita – História do Funchal. Associação Académica da Universidade da Madeira. Grafimares, Lda. 2nd Edition. Funchal. 2017.

17th and 18th Centuries: Remodeling the Urban Environment of Funchal:

The wealth deriving from wine production, especially relevant in the 17th and 18th centuries, allowed for a refurbishing of the urban mesh in the island, particularly in Funchal, where palaces, houses, offices and shops were built. To replace their small one-storey dwellings, Funchal merchants built houses with cellars where they kept the barrels. There are still some houses dating from this time. These buildings had laced facades in black stone and iron verandas with many windows and the typical tower to watch the ships arriving (adapted from Vasconcelos, 2008).

During the 19th century, this economic cycle brought new dynamics to the outskirts of the city as the number of farms increased, many of which owned by English merchants. These farms had magnificent gardens and, almost always, a small construction, a gazebo, at a corner of the garden, the so-called “house of pleasure”, as well as a chapel for the religious life of the family and their servants (Vasconcelos, 2008).

The well-being brought by wine export ended in the first half of the 19th century, since, in the second half of the century, there was a steep decrease in export and in the living conditions in the island. There are still good examples of the architecture of that time which are now used for health tourism, as is the case of the farms (adapted from Vasconcelos, 2008).

Image 5 – “Map of Funchal at the time of Captain Skinner (1775), copy of details of Map by Willian Johnston, ed. London, 1791. Collection Rui Carita, ARM”. Rui Carita – História do Funchal. Associação Académica da Universidade da Madeira. Grafimares, Lda. 2nd Edition. Funchal. 2017.

The vulnerability, the restraints and the responses provided by land management

In 1803, a flood i, consequence of the state of erosion of the margins of the streams caused great damages to the island. The governor claimed the visit of a skilled engineering official to the island to supervise the repairs to those damages (adapted by Carita, 1982).

The flood allowed for a modern perspective for Funchal. The devastation led to the implementation of health measures and improvements in the image of the tourist city. The three streams that cross the city were channeled, their beds corrected and widened, or side canals were open (Perdigáo, 2015).

Brigadier Reynaldo Oudinot, in charge of cleaning and reconstruction, proposed a bourgeois housing neighbourhood in the Plan for the New City in Angústias (dated 1804), which would have an orthogonal shape and a wide square in the centre, in the land next to the pre-existing city. This proposal announced the intentions for planned and organized urban expansion according to the orthogonal models that were emerging in Europe, with different areas and social segregation. The plan was not implemented but the fact that an important road and a fountain were built allowed for detached houses being constructed in that very special area (Perdigão, 2015).

Image 6 – “Map of the City of Funchal, Oudinot, 1804. Source CMF”. 100 Anos do Plano Ventura Terra, Funchal a Cidade do Automóvel. OASRS – Delegação da Madeira. Funchal. 2015.

At the end of the 19th century, there were traces of the medieval borough in Funchal, evidenced in the spontaneity of its urban development and the guidelines established at the time of the early settlements. The city was in its early stages. That was what evidenced city councillor José Joaquim Freitas on the city’s cleaning system when he described Funchal’s narrow, winding and badly paved streets, where there was no drinking water, no sewers, with many dirty stables, one cemetery, a gaol and a hospital in the centre of the city, in the middle of the noise and bustle of the city. These circumstances were not favourable to the image of the city, in which tourism, and in particular health tourism, was already an important source of income for the regional economy (adapted from Vasconcelos, 2008).

In the transition to the 20th century, Funchal aimed to keep up with the modern times of the most important European cities. The wall had been replaced by the streets, the gardens and urban enhancements, as well as by the first modern equipment and infrastructures (adapted from Matos, 2015a).

Image 7 – “Tour map of the City of Funchal. Trigo 1910. CMF and General Maps. Adriano Trigo. 1905. CMF”. 100 Anos do Plano Ventura Terra, Funchal a Cidade do Automóvel. OASRS – Delegação da Madeira. Funchal. 2015.

With the implementation of the Portuguese Republic, the new local powers wanted an urbanization plan for the city that would change Funchal and provide it with modern urban equipment and new infrastructure in order to develop international tourism, the most important economic activity of the island. Ventura Terra responded to the challenge (Vasconcelos, 2015). For the first time, the city was seen as a whole, and the repairing and modernizing measures were extreme: wide boulevards with two-lane streets and a central green area for pedestrians would cross the city and solve road issues. The beach was replaced by a “beautiful waterfront avenue, 50 metres wide and 1255 meters long” (Terra, 1915 – quoted by Matos, 2008); João Gomes stream, after being channelled, would be replaced by an avenue; the neighbourhood of the old Civil Hospital – one of the most beautiful 17thc buildings – would be demolished; Carreira Street would be widened; the Cathedral and São Lourenço Palace would be reduced and in the east and the west of the city centre, two urban parks would be built, one rather large (Matos, 2015a), in the name of “health, entertainment for the population, comfort and welcome of tourists” (Terra, 1915 – quoted by Matos, 2008),

These measures were taken in the name of common good and progress and would become part of the so-called “enhancement plans”. The model was Haussman’s Paris, already present in “Memoire sur les études d’amèliorations et emblissements de Lisbonne” that Pézerat published in 1865. This was the idea behind Ventura Terra’s Enhancement Plan for Funchal, which aimed to provide the city with the efficiency and glow of Paris (adapted from Matos, 2015a).

This plan was important for the urban planning of Funchal in the first half of the 20th century. Terra designed a modernization proposal for the city, the first of this magnitude in the archipelago, in which the current concepts of French urban planning were applied and made visible in the large straight avenues, in the use of roundabouts to distribute traffic and in the wide squares and parks in the outskirts. However, this vision, perhaps because too ambitious for the time, was not implemented (adapted from Vasconcelos, 2008).

Image 8 – “Enhancement Plan for Funchal. Map. Source CMF”. 100 Anos do Plano Ventura Terra, Funchal a Cidade do Automóvel. OASRS – Delegação da Madeira. Funchal. 2015.

Between 1931 and 1933, architect Carlos Ramos was responsible for the Urban Plan for Funchal, at a time when these plans decided the bases for planning changes in the urban area. Though more restrained in his views of the city as a tourist destination, Ramos focused his concerns in redefining the urban centre and proposed its modernization based on the road network, equipment and housing, following the principles of the previous plan. This plan was not implemented either.

In 1935, Ventura Terra’s Plan was resumed by Fernão de Ornelas, who was the president of Funchal Municipality. Though the plan was not implemented as designed, the construction carried out aimed at modernizing Funchal, which followed the plan, and was important for what the city is today (adapted from Perdigão, 2017). Arriaga and Zarco avenues (former Passeio Público) were widened and lengthened and became important links for traffic. The lengthening of Zarco Avenue was the responsibility of landscape architect Caldeira Cabral, who was also responsible for its link to the eastern side of the city through Bom Jesus Street and the Município Square, created by the

City Hall by architect Faria da Costa, at the centre of which there is a fountain by architect Raul Lino. The layout of Oeste Avenue was completed, now under the name Infante Avenue, which consolidated the expansion of the city to the west, leading to hotels being built in the following stage of the plan (Perdigáo, 2017).

In 1941 and 1942, Caldeira Cabral was responsible for designing the layout of Marginal, or Mar Avenue, on Praia Street and up to São Tiago armoury, as well as for building Parque da Cidade, the City Park, (today Santa Catarina Park), as compensation for redesigning the layout of Arriaga Avenue and the improvements made to Jardim Municipal (1942). At the same time, equipment was installed, as well as basic sanitary facilities and electricity network, in the suburban areas as a means of promoting public health (Perdigão, 2017).

Public construction and urban enhancements were in accordance with the policies of Estado Novo, aimed at providing an economic boost and employment for the population, as well as, most importantly, the tourist image of modern Funchal (Perdigão, 2017).

Image 9 – “Map of the City, 1948-1950. Source CMF”. 100 Anos do Plano Ventura Terra, Funchal a Cidade do Automóvel. OASRS – Delegação da Madeira. Funchal. 2015.

The First Master Plan for Funchal, the Rafael Botelho Plan:

Funchal was one of the first Portuguese cities to have a Master Plan. Coordinated by architect Rafael Botelho, its design was preceded by a debate open to the community and which took place in 1969 with the conference Colóquios de Urbanismo. That led to a publication under the same name, which evidences its pioneering and democratic features. Topics such as safeguarding the historical city (based on the invaluable survey by António Aragão), the maintenance of the farms and the preservation of the extremely original landscape of the entrance to the city were the main concerns that the plan aimed to maintain, becoming the first planning tool of the island considering Madeira as a whole and bearing in mind public interest, qualification of the urban space and the well-being of the community (adapted from Matos, 2015b).

Image 10 – “1972 Master Plan – Scheduled Operations. Rafael Botelho. Map. Source CMF”. Plan by Rafael Botelho, Funchal 1969/72. OASRS – Delegação da Madeira. Funchal. 2015.

Political Autonomy and the New Land Development Model for the Region:

From 1950 onwards, the development of car transport and the increase in the number of vehicles in the island led to the need for new roads. However, the Colonial War, in the 1960s and 1970s, together with the political instability and the financial crisis after the Revolution on 24th April 1974, led to only a few of these roads being constructed. In 1975, the road network was only 265 km long (Simões, 1983 – quoted by Dantas, 2012), and remained unchanged until the end of the 1990s (Dantas, 2012).

In 1970, most of the population still lived from agriculture. The urban space was only a few residential areas, such as the towns that were municipal capitals and the city of Funchal, an area that included Santa Maria Maior to Ponte do Ribeiro Seco. The roads connecting the areas in Madeira were narrow because the orography did not allow for wide ones, many houses did not have electricity or running water, especially due to population dispersal. Mobility was also very reduced in this rural environment (Dantas, 2012).

The accession to the EEC (1986), boosted the country’s economy, through EEC aid, and allowed for investment in infrastructures. The Autonomous Region of Madeira (RAM) committed to building roads and basic infrastructures, namely in running water, electrical and basic sanitary networks, which were almost non-existent in the Islands (Dantas, 2012).

The development of the media and transportation led to a new dynamics between the centre and the outskirts of the cities, shortening the distances among the residential areas, diversifying economic activities, increasing private investment, namely in real estate and in new hotels, which caused profound changes in how the urban space was organized and expanded, in particular with the more and more common use of the car. This invaded remote areas, allowed for suburban and periurban, non-structured growth in view of the roads that were built, and which dispersed residences and took them to more and more distant areas and contributed to new centres appearing.

In the archipelago of Madeira, for more than four hundred years, there was only one city – Funchal. This situation changed after the 1950s, with five more cities being founded, four of which in the southern slope of Madeira: Câmara de Lobos, Caniço, Santa Cruz and Machico, and one in the northern slope: Santana (Dantas, 2012).

At regional context and with the exception of Funchal, for many years, the urbanization process developed in a context of lack of land management policies (Dantas, 2012). Only in 1995, after the approval of the Regional Legal Decree n.o 12/95/M, of 24 June, amended by Regional Legal Decree n.o 9/97/M, of 18 July the first (and so far only) Land Management Plan of the Autonomous Region of Madeira (POTRAM) is also approved. This legal document lays down the guidelines for planning and developing interventions on land use and occupation, defence and protection of the environment and the historical heritage, population distribution and the structure of an urban network (Fernandes, 2011). However, in practical terms, POTRAM became an often ignored and secondary tool for land management whose importance is still not understood today, at a time when there were very rapid and profound changes in the island and its occupation, hardly influenced and often going against the established guidelines, as is the case of the occupation of the coastline and the urban expansion to higher and higher areas. This has placed in danger the bio-physical, environmental and security balance of urban centres, towns and cities, which become more vulnerable to climate hazards. Moreover, those who live in higher areas are also in danger due to lack of basic infrastructure and public space.

Image 11 – “POTRAM. Management Plan” Source Governo Regional da Madeira. Funchal. 1997.

In 1997, the Municipality of Funchal approved its Master Municipal Plan (PDM), whose main objectives were to contribute to a shift in the economic activities from tourism to traditional activities and other alternative activities that could provide added value, contribute to taking competitive advantage associated to the existence of high quality education/training systems, of science and technology, rationalize and program urban increase and upgrade the functional structure, preserve and enhance all the district’s natural resources, protect and manage the green structure, meet the needs of the district in terms of accessibility and transportation systems, improve the coverage level in the main urban infrastructures, preserve, refurbish and protect cultural heritage, develop and detail laid down rules and directives at higher level, provide data for planning, namely, to design other municipal plans or regional or sub-regional plans, provide a framework to design activity plans for the district and allow the district to create an urban management structure per land units, which would be autonomous (PDM, Funchal, 2008).

This plan was designed at the same time as POTRAM, though it was hardly influenced by it. The lack of practice in planning and the low political interest for these tools caused them to lack in their much-needed complementariness and harmony.

The PDM allowed to think of the Municipality as a whole and attempt to manage the urban expansion outside the older neighbourhoods, introduced the minimum land size for building (400m2), urban indexes to control soil sealing and the building volume. The PDM also introduced rules on the minimum areas between buildings and rules on alignment among buildings that allowed for streets to be more organized. Unfortunately, and when it was already evident that the city was expanding to the higher areas of the island, and the consequent building of illegal houses, the plan was unable to contain the uncontrolled expansion towards the mountain, making this the most vulnerable area to risk of flooding, of flooding of the main streams, of forest fires, considering its closeness to the cities and its lack of accessibility and quality public space. Like POTRAM, this land management tool was not used for balanced management of the municipal land, which endured high pressure from real estate forces and led to the loss of important heritage buildings and was unable to protect the coastline from uncontrolled hotel occupation that strongly conditioned citizens’ access to the sea.

The PDM laid down the expansion to the west, namely to Ajuda and Amparo, where a new centre emerged.

While this PDM was in force (20 years), several Urbanization Plans (PU) were designed, namely for Amparo, Palheiro, Infante, Levada do Cavalo, Ribeira de Santa Luzia and Ribeira de João Gomes. The Detail Plans (PP) designed were those for Castanheiro, Praia Formosa, Projeto Urbano AR1/CE de Santa Luzia, Quinta do Poço and Vila Giorgi.

Many of these significantly changed the PDM, some in a positive way (as was the case of Amparo PU), redefining the proposed urban design, the buildable rates; others in a negative way, as was the case of Infante PP, which allowed that very big buildings were constructed for tourist purposes which had a huge impact on the landscape.

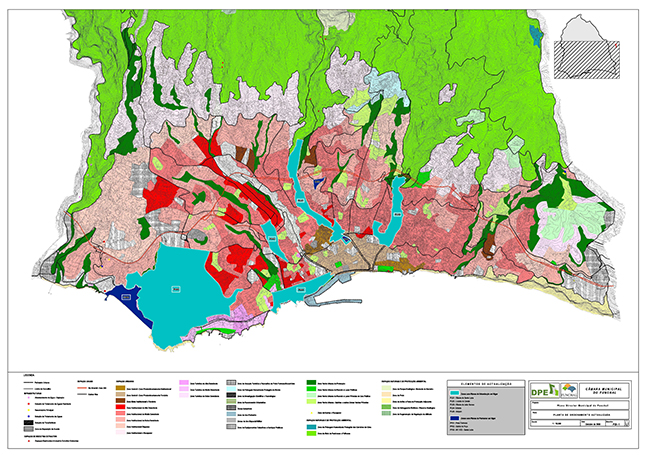

Image 12 – “PDM Funchal. Partial Management Plan” DPE – CMF. 2008.

In the first decade of the 21st century, a new set of Master Municipal Plans are designed for the remaining nine districts. These plans are considered basic land management tools aimed at contributing to coherent development model for the several municipalities by providing general guidelines for urban planning and management. Many of these municipalities are still lacking Urbanization Plans or Detail Plans.

The late designing of these tools had several consequences, namely in Funchal’s neighbouring districts (Santa Cruz and Câmara de Lobos), where the lack of planning and regulations in building, together with a high pressure from real estate agents, led to several issues such as excess of soil sealing, inadequate sizing of infrastructures, parking spaces and streets, disfigurement of the landscape, lack of space and public equipment.

Noteworthy is also the fact that the PDM in Madeira are designed to allow access to EEC funds, which had not happened so far, even though there was a national guideline following the publication of Decree-Law n.o 69/90, of 2 March.

In the middle of this decade, a second stage began for the Master Municipal Plans. The amendments to these tools were introduced because they were outdated in view of current land dynamics. This process is already complete at the municipalities of Ponta do Sol, Ribeira Brava, Calheta, Santana and Funchal and the PDM in Câmara de Lobos is already under public debate. All these land management tools have in common a new perspective on the land, focusing on urban expansion and the need to limit it, namely towards the highest areas of the island; restrain the occupation of risk areas, defining special intervention units that allow attaining operational goals aimed at promoting and fostering classification of the soil, updating and managing the road network, urban rehabilitation, urban mobility and the creation of more and better public space. It is also rather evident the cross-sectional concern in redefining areas linked to economic activities.

Image 13 – “PDM Ponta do Sol. Management Plan” Source CMPS”. 2013.

In 2017, other amendments were laid down by Regional Decree n.o 18/2017/M, of 27 June, in regards to regional land management system in Madeira (until then regulated by Regional Decree n.o 43/2008/M, of 23 December), thus adjusting the region to Law n.o 31/2014, of 30 May. This law laid down the current bases for public policy on land, land management and urban planning, pursuant to article 81, of Decree Law n.o 80/2015, of 14 May, which developed those bases and defined the regime for national, regional, inter-municipal and municipal coordination in land management, the general regime for land use and the regime for designing, approving, implementing and assessing land management tools.

What is missing – A critical analysis:

Though the region is revising its municipal planning tools, its main strategic tool must urgently be revised, which, in terms of the regional land management system, will now become the Programa Regional de Ordenamento do Território da Região Autónoma da Madeira (PROTRAM). This tool will allow a current perspective of the territory and define an integrated development strategy (rather than disjointed, as it is now), allowing to conciliate policies and shortcomings that do not promote an integrated and effective management of the region.

Ninety-eight percent of the regional population lives in the island of Madeira. The socioeconomic vulnerabilities and the environmental risks must be identified, studied and minimized, must be integrated in the land management and regulation tools should be revised or laid down considering the increasingly important and recurring effects of climate change, of the changes required by the new economic and social development paradigm, previously based on infrastructure and the response to the population’s basic needs, as well as on sustainability and social and territorial cohesion that must exist in the future of these islands (adapted from Barroco, 2012).

Besides this, the region should promote the implementation of other land management tools, namely special programs, Programas Especiais de Ordenamento, firstly those related to the coastline, Programas de Ordenamento da Orla Costeira (POOC), which have not been implemented in Madeira yet, a unique situation in the country. The several regional reserves – the Ecological and the Agricultural – should also be defined, since today they are mere outdated limits of the natural park and the areas more fitted to agriculture are not subject to any specific procedure, which goes against the existence of special regimes, and thus allow for a realistic PROTRAM.

Today, a new perspective on these tools seems to exist. The launching of a competition to design Madeira’s POOC is previewed until the end of 2018 (the designing of Porto Santo’s POOC has already started), and that of the new PROTRAM, which renews our hope in more efficient land management.

Bibliography

ACAPORAMA – Caraterização do Território. Grupo de Ação Local ACAPORAMA. Funchal. 2016. Consultado em: 13/07/2018. Site: http://www.acaporama.org/proderam2020/index.php/a-estrategia/caracterizacao-do-territorio

ARAGÃO, António – O Espírito do Lugar, A Cidade do Funchal. A. Aragão. 1ª Edição. Rio de Mouro. 1992.

BARROCO, Ana; AFONSO, Rute – Planeamento Territorial nos Territórios Insulares Portugueses. Malha Urbana. Nº 12. Lisboa. 2012.

CARITA, Rui – Arquitetura Militar na Madeira, Séculos XVI a XIX. Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian. Lisboa. 1982.

CARITA, Rui – História do Funchal. Associação Académica da Universidade da Madeira. Grafimares, Lda. 2ª Edição. Funchal. 2017.

DANTAS, Maria Gilda de Andrade Fernandes – A Rede Urbana e Desenvolvimento na Região Autónoma da Madeira. Dissertação de Doutoramento em Geografia e Planeamento Territorial, Especialidade em Planeamento e Ordenamento do Território. FCSH-UNL. Lisboa. 2012.

DECRETO LEGISLATIVO REGIONAL n.º 18/2017/M, 27 de junho. JORAM. 2ª Série. 2017.

FERNANDES, Fabiana Laura Candelária. Ordenamento do Território em Pequenas Ilhas: Caso de Estudo da Madeira. Dissertação de Mestrado em Engenharia do Ambiente. Universidade de Aveiro. Aveiro. 2011.

MATOS, Rui Campos – Nos 100 Anos do Plano Ventura Terra. 100 Anos do Plano Ventura Terra, Funchal a Cidade do Automóvel. OASRS – Delegação da Madeira. Funchal. 2015. (a)

MATOS, Rui Campos – Uma Ideia de Cidade. Plano Rafael Botelho, Funchal 1969/72. OASRS – Delegação da Madeira. Funchal. 2015. (b)

PERDIGÃO, Cristina – Alvores da Modernidade no Funchal Oitocentista. 100 Anos do Plano Ventura Terra, Funchal a Cidade do Automóvel. OASRS – Delegação da Madeira. Funchal. 2015.

PERDIGÃO, Cristina Sófia Andrade – O Turismo na Madeira, Dinâmicas e Ordenamento do Turismo em Territórios Insulares. Dissertação de Doutoramento em Urbanismo. FA-UL. Lisboa. 2017.

POTRAM – Regulamento. Governo Regional da Madeira. Funchal. 1997.

PDM FUNCHAL – Regulamento. Câmara Municipal do Funchal. Funchal. 2008.

VASCONCELOS, Teresa – O Plano Ventura Terra e a Modernização do Funchal (Primeira Metade do Século XX). Coleção Funchal 500 Anos. Empresa Municipal Funchal 500 Anos. Funchal. 2008.

VASCONCELOS, Teresa – Ventura Terra no Funchal: Um Plano Centenário. 100 Anos do Plano Ventura Terra, Funchal a Cidade do Automóvel. OASRS – Delegação da Madeira. Funchal. 2015.

Biography

José Roberto Ribeiro Rodrigues – architect, holds an Integrated master’s in architecture (2015) by Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa (DA-UAL) and is attending the Master in Land Management & Geographical Information Systems at FCSH – UNL.

He works for the Technical Office of Ponta do Sol Municipality. His professional activity is currently suspended as, since 2011, he has been a Member of the Legislative Assembly of Madeira, in which he has presided over the 3rd Specialized Commission on Environment and Natural resources since 2017.

He has an architecture office since 2016 – RR Arquitecto – Arquitectura + Planeamento Urbano – in which he continues to work on regional projects.

e-mail: rrodrigues.arquitecto@gmail.com.

[1] Flood: a rising and overflowing of a body of water especially onto normally dry land Merriem-Webster Dictionary: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/flood