Rosário Salema

maria.salema@cm-lisboa.pt

Landscape Architect, Lisbon City Council, Municipal Directorate of Urbanism, Department of Public Space, Public Space Project Management Division, Portugal

For citation: SALEMA, Rosário – The double condition of a Place: Memory and Future. Estudo Prévio 22. Lisbon: CEACT/UAL – Centre for Architecture, City and Territory Studies of the Autonomous University of Lisbon, 2023, p. 99-115. ISSN: 2182-4339 [Available www.estudoprevio.net]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.26619/2182-4339/22.HEP.2

The Double Condition of a Place: Memory and Future

Abstract

The public space of the city is the space of the collective. To inhabit the public space is to exist collectively and in interaction: in the street, in the square, in the market, in the park, etc. Over time, various ways of inhabiting the public space are inscribed in the city, like layers of the city’s history that overlap in a palimpsest. The floor inscribes the history of the collective in the city.

Acting on public space, as a designer, naturally implies knowing and investigating these layers of time. To intervene in the public space is to open the possibility of knowing and revealing the collective history of the city, often diffuse and anonymous.

Using the symbolic value of the layers of time in public space projects in the city of Lisbon allows us to put the present and the past in dialogue and give meaning to the “new” places.

Keywords: landscape architecture, Lisbon, geomonument, memory, Largo da Graça, Jerónimos Monastery

I understand that the public space of a city constitutes a powerful archive of collective memory and that historical research constitutes the basis of the design methodology. Through this research, it is possible to put the past and the present in dialogue with one another and rescue a meaning for the “new” places.

We will talk about two works of public space that I carried out in the Lisbon City Hall through which this methodology is exemplified.

Geomonument of Rua Sampaio Bruno – Here there was the sea twenty million years ago

This project, carried out in 1998, was developed in collaboration with the National Museum of Natural History of the University of Lisbon, and follows the implementation of a Protocol for the protection of the geological heritage of the city.

At the head of the classification and protection of that geomonument, as well as many others in Lisbon, was Professor Galopim de Carvalho who, for years, was committed to the valorization and preservation of the various geological landscapes of the city.

Figure 1 – Geomonument of Rua Sampaio Bruno (Source: CML, 2008)

Most people do not recognize the existence of geomonuments in the city, but identify a number of escarpment situations. One of the best known is the escarpment located at the top of Avenida Duarte Pacheco, at the entrance of the city, where a monument to Almada Negreiros, by Leonel Moura, is located, near the towers of Amoreiras shopping mall. There is Another one in Avenida Infante Santo, next to the first traffic lights up the hill. Currently, there are eight geomonuments classified in Lisbon.

For many of us as children, these sites were rocks of exploration and adventure, long before they were classified as a geomonument. I remember being a child and spending hours digging in the escarpment of Avenida Infante Santo to look for fossils for my collection. And to think that the sea had once been there.

The geomonument of Rua Sampaio Bruno is located in Campo de Ourique borough. What a challenge it is to imagine that landscape being formated into a geomonument.

We are in the Miocene period, about twenty million years ago, when Lisbon was submerged under water, up to the level of one hundred meters of altitude. Back then, the only areas that emerged from the water were the Monsanto mountain range, Eduardo VII Park, Campo de Ourique, São Jorge Castle, Alto de São João area and the Airport, located above 100m of altitude.

Twenty million years ago, Campo de Ourique was a tepid, transparent and shallow sea with reefs and corals on the surface. A tropical landscape. That reef was inhabited by millimeter-sized invertebrate animals that lived in small colonies (Figure 1) and resembled corals or deep-sea plants. They are bryozoans (animal moss, in literal translation from the Greek). They are frequent in sedimentary rocks and abundant in today’s seas. They are distributed at all depths and latitudes in the marine environment.

After the Miocene period, the sea began to descend and the corals fossilized. In these fossils was kept, an important history of the evolution of the landscape of Lisbon, long before the city existed.

Figure 2 – Image of living Bryozoans (Photograph: Daniel Stoupin in the article published on 23/07/2012 in the Planet of Invertebrates).

The geomonument of Rua Sampaio Bruno was classified in 1997 and is located a little above the cemetery of Prazeres, towards Monsanto Park, at the level of 100m above sea level.

At the beginning of the project, we had a sediment 3m high and 20m long, located between buildings. It had once been an escarpment, but successive works in the surrounding area substantially reduced its size and expression in the city.

The challenge of the project was to create a scientific and didactic space to support the National Museum of Natural History and the University of Lisbon. At the same time, it would inform citizens about the geological evolution of the city’s landscape.

To safeguard the geomonument, which was threatened to collapse, we installed a metal mesh and built a concrete support wall along its entire length. At the rear of the support wall was placed a panel of tiles. This panel enunciates a tear over the sediment and reveals images of the bryozoans, magnified thousands of times. It was a very interesting process since, it was fundamental to illustrate the fossilized images and reveal what was not possible to see through a naked eye. In the beginning, Professor Galopim de Carvalho wanted the images to be drawn on the Portuguese sidewalk. We understood that we ran the risk of losing scientific rigor and opted for photographic printing on tile.

Figure 3 – Geomonument of Rua Sampaio Bruno Image of the Bryozoans on tile panel, at the rear of the geomonument, detail (Source: CML, 2021)

Figure 4 – Geomonument of Rua Sampaio Bruno Image of the Bryozoans on tile panel, at the back of the geomonument (Source: CML, 2021)

To highlight the absolutely extraordinary fact that this sediment existed since the Miocene we engraved, on the border face of the wall, next to the sediment, the phrase “Here there was the sea 20 million years ago”. The phrase causes a leap in time and poses a great challenge of imagination. It is hard to imagine, whatever it is, before history, because we have so few images. The installation of the phrase generated a deep respect for that sediment that became part of the daily life of the neighborhood and rescues, in the city, a relationship with a time about which there is no memory whatsoever. The inscription of the phrase on the wall opens the way to imagination and curiosity and transforms the space, between buildings, into a new place in the city.

Figure 6 – Geomonument of Rua Sampaio Bruno, detail (Source: CML, 2008)

Largo da Graça – A Square Gate between the city and the countryside

The project for Largo da Graça took place between 2007 and 2012 and arose under the program “A square in each neighborhood”, which main objective was to create new centralities in the city and requalify public spaces relevant to the life of the neighborhood. In general, the interventions promoted the increase of pedestrian areas and the reduction of car circulation and parking areas.

The Graça square encompasses the entire area to the East and South of the Graça Convent building. Most people do not realize that the square covers this entire dimension area and identify the square as being the area of the belvedere of Graça or the area of the terminal of the tram 28.

Because the square has a very diffuse and unclear area, there are six toponymic plates to identify it. At each corner of the buildings there is a sign, at the meeting of each of the paths that lead to the square.

It is essential to understand that a square is not, actually, a square. A square results from a formal urban design, usually geometric, and defined by the architecture that surrounds it. A result from the encounter between paths that generate an informal space. The Graça square results from the meeting of paths that lead to the Convent of Graça.

Figure 7 – Orthophotomap of Largo da Graça (Source: Google Earth Pro, 2012)

Figure 8 – Orthophotomap of Largo da Graça (Source: Google Earth Pro, 2012)

When the Largo da Graça Project began, we understood that there were two very distinct environments: to the South of the convent an area of great tourist movement: the Gustavo Gil garden, the Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen belvedere, the churchyard of the Church of Graça and the old palaces; the source of the convent, the terminal of the tram 28 and a great concentration of commerce and restoration, which constitute the heart of the daily life of the neighborhood.

It was through cartographic research that we understood that the difference between the two zones had a very remote origin. It was the Fernandina Fence that, when deployed, divided the zone, of what would one day be the square, into two areas.

At the time of the construction of the Fernandina Fence (1373-75), it bypassed the convent of Graça and confined it to the interior of the city, leaving out all the agricultural fields, to the North and East, that belonged to the convent. The existence of the fence gave rise to distinct evolutions of the intramural and extramural areas over time. On the intramural side, south of the convent, would be the city. The outer side of the fence would remain, for centuries, very sparsely inhabited, with the agricultural land of the convent fence and the large farms that supplied vegetables and fruit to the city. The construction of the Fernandina Fence, thus, gave rise to a separation between city and country. The source of the convent was the Postigo da Nossa Senhora da Graça (Our Lady of Grace) that materialized a door between the city and the countryside.

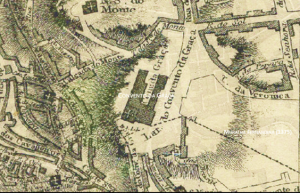

Figure 9 – Cartography of Tinoco 1650 (Source: Lxi CML)

In the intramural area, next to the convent, the city is consolidated and, from the 16th century, sees the emergence of several palaces, such as the current Vila Sousa, which in times would have been the Palace of the Valley of the Kings and the Palace of the Lords of Trofa, to the west of Vila Sousa. After several earthquakes, particularly that of 1755, the fence disappeared, almost entirely.

Only at the beginning of the 19th century, it appeared for the first time, the toponym “Largo do Convento da Graça” (cartography of Duke Wellington, 1812). The definition of square appears only after the earthquake of 1755, that is, after the disappearance of the Fernandina Fence, which allowed the city to expand into the old extramural zone. Following this urban expansion, the square began to gain configuration to the north.

Figure 10 – Cartography of Duke Wellington, 1812 (Source: Lxi CML)

The farms and agricultural fields were parceled out and allotted at low construction costs, giving rise to strict buildings and quite tall for the time. The low construction costs allow the installation of a population, mostly working-class.

In the mid-19th century, the extramural area was fully consolidated and it is at that time that the square acquired the configuration that we know today.

The fence no longer exists now, but the difference between “inside” and “outside” remains and translates into the different characteristics of each of the zones. The understanding of this circumstance becomes fundamental for the project because it explains the bipolarity of the square and allows to assume and exalt the differences between the two zones.

Figure 11 – Cartography Filipe Folque, 1855-58 (Source: Lxi CML)

In order to promote the spatial unity of the whole square, it was decided to create a common floor to establish the connection between the various parts of the square and, at the same time, to ensure continuity with the streets and surrounding spaces. This continuity was quite important since the square constitutes the center of the neighborhood where all the streets converge and the idea was to strengthen the connection of the entire network of paths of the neighborhood with its center.

The limestone was systematically used, in the form of sidewalks, blocks and slabs of larger and smaller dimensions. This material, traditionally used in Lisbon, allowed to adopt a coherent system for the entire pavement and solve all technical situations: rainwater collection (sinks), ditches, comfortable strip, sidewalks, etc. and, at the same time, made it possible to overcome the challenges of topography.

The square was a complex and fragmented space. The sidewalks were quite narrow and the bituminous pavement covered more than 70% of the area. The square was almost exclusively used as a car park. The challenge was to reverse the situation: widen pedestrian zones, reduce car traffic areas and, as far as possible, reduce parking.

Figures 12, 13 and 14 – Largo da Graça (Source: CML, 2007)

It was through a memory inscribed in that space that allowed to radically alter the road network and considerably expand the pedestrian areas.

On a visit to the site with my colleague Álvaro Tição, historian of the Lisbon City Council, we learnt of the existence of a well-hidden secret in an area next to the convent. It was a phrase inscribed at the base of the wedge of the Palace of the Lords of Trofa: “Here comes the churchyard of Graça”.

Figure 15 – Palace of the Lords of Trofa (Source: CML, 2009)

Figure 16 – Palace of the Lords of Trofa – inscription at the base of the wedge of the Palace (Source: CML, 2009)

With the discovery of this phrase we understood that the space of the churchyard of Graça, reduced at the time of the project, to the border area at the door of the Church of Graça, next to the belvedere, would have been much larger in times. This meant that the entire Augusto Gil garden would have been part of the old churchyard of the convent.

Figure 17 – Orthophotomap of Largo da Graça (Source: Google Earth Pro, 2012)

This was how the identity of this area of the square was defined: the churchyard of the convent. The identity of the nascent zone would be centered on the existence of the tram terminal 28, symbolic reference of the neighborhood and the expansion of the city in the 20th century. Two times, two zones, one floor, one square.

With the discovery of that phrase we managed, with the support of the General Directorate of Cultural Heritage, to remove the car lanes to the South and Southeast of the convent, as well as much of the parking. The churchyard was frankly enlarged to the South and Southwest of the convent. The whole garden became part of the new churchyard and the facades of that building gained a huge prominence.

Figures 18 and 19 – Largo da Graça: Zone of the churchyard of the convent of Graça, before and after the work (left Google Earth Pro 2012 and right FG+SG Fernando Guerra, 2017).

The inscription of the phrase on the wedge remains hidden. Nothing has been done to reveal it or make it more visible. We considered it important to keep the secret, as before.

Figure 20 – Largo da Graça: new churchyard of the convent southeast zone (FG+SG Fernando Guerra, 2017)

Figure 21 – Largo da Graça: new churchyard of the convent south zone (FG+SG Fernando Guerra, 2017)

In the terminal area of tram 28 it was also possible to remove a road next to the buildings, as well as all the parking and create a small square for reversal of the tram. A new churchyard for the convent and a new space for the tram terminal 28.

Figure 22 – Largo da Graça: new terminal of tram 28 (FG+SG Fernando Guerra, 2017)

Finally, I recall that in the case of the geomonument we inscribed a phrase that enunciated the memory of the place in the city. Here, in the square of Graça, we found a phrase that revealed and recovered the memory of the place. The double condition of a Place: Memory and Future.

Note: For the realization of the project of Largo da Graça, it was fundamental the collaboration with the atelier Bugio (João Favila and Miguel Moreia) and Campo d ́Água (Marta Azevedo).

1 Lecture delivered on December 15, 2021, in the discipline of Seminars I and III 2021, under the theme “Inhabiting Public Space”. Coordination: Bárbara Silva.