Álvaro Domingues

Geographer. Professor at FAUP and researcher at CEAU-FAUP.

Ana Silva Fernandes

Architect. Researcher at CEAU-FAUP.

How to quote this paper: DOMINGUES, Álvaro; FERNANDES, Ana Silva – THE URBANIZATION OF POVERTY – academic training and social awareness. Estudo Prévio Lisbon: CEACT/UAL – Centro de Estudos de Arquitetura, Cidade e Território da Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa, 2015. ISSN: 2182-4339 [Available at: www.estudoprevio.net]

Abstract

The urbanization intensification process of the last decades is well-known, as well as its asymmetry. However, looking at generalized urbanization is often confused with a generalized look at urbanization. In this sense, contrary to the adoption of homogenizing models, it will be necessary to re-equate the meaning and the challenges of the present urban condition, looking for the conceptual, critical and operative tools to deal with territorial diversity and socio-economic disparities.

Taking the Urbanization of Poverty course unit recently created in the Faculty of Architecture of the University of Porto as a point of reflection and pedagogical tool, this paper reflects on the training of architects and urban planners and examines the need to reinforce a practice and a broadened awareness that pay more attention to the asymmetries of urbanization and the social role of the different actors in the process of management and transformation of the built environment.

Keywords: urban condition, regime of visibility, urban epistemology, accelerated urbanization, urbanization of poverty

Introduction

“C’est une forme mentale et sociale, celle de la simultanéité, du rassemblement, de la convergence, de la rencontre (ou plutôt des rencontres). C’est une qualité qui nait des quantités (espaces, objectes, produits). C’est une différence ou plutôt une ensemble de différences. (…) En tant que lieu du désir et lien de temps, l’urbain pourrait se présenter comme signifiant dont nous cherchons en ce instant les signifiés (c’est-a-dire les “réalités” pratico-sensibles qui permettraient de le réaliser dans l’espace, avec une base morphologique et matérielle adéquate).”

Henri Lefebvre, Le Droit à la Ville (1968)

The recent trivialization of the expression Urban Age or the thousand-fold statement that more than half of humanity lives in cities has contributed to a growing confusion about “cities” and urbanization processes. Due to the lack of epistemological criticism, this confusion was already in place before this situation took place.

By the late 1960s, it was already very clear to authors like Manuel Castells – The Urban Question – or Henri Lefebvre that the conventional approach to urban topics in Europe and the US (the dominant focus on theoretical and empirical production) was too much attached to a certain cultural and bourgeois historicism. Until then, the city had been perceived, above all, as a spatial unit, a type of settlement characterized by density, agglomeration and functional diversity: cities – with their own name and location on the map – would have a clearly defined form, centre and boundary; each city would correspond to a “whole”, to a defining body, at the same time, to an identity, a history, a common living system and, therefore, social organization.

Being both territory and society, mode of regulation and vision of the world, analytical and normative field, fact, imagination and representation, the city has become a supposedly self-explanatory and transdisciplinary vague category. Intending to be a concept and a scientific object that is simultaneously sociological, geographic, urban, and economic, and also a common sense expression of extreme flexibility, city is a word/imaginary thing that is ready to be colonized with the most diverse and contradictory meanings – too much polysemy for the minimum rigour required in any disciplinary field.

The opposite of the city would be the territory – the figure and the background, respectively – and the urban/rural or city/countryside dichotomy distinguished an opposition judged to be stable. The so-called Chicago School – authors such as Louis Wirth and his celebrated expression “urbanism as a way of life” (1938) -, by focusing on an urban ecology, associated the industrial metropolis (the symbol of the modern) with a particular location, a morphology and a way of life. As G. Simmel had already repeatedly studied, the geographical space of the city was synonymous (or receiver, or container) of the industrial and the modern as opposed to the agrarian and the traditional – Ferdinand Tönnies’ Gemeinschaft/Gesellschaft, Community/Society dichotomy (1887), taken up by Max Weber (1921) as a key element of social change and historical evolution.

This panorama gives us a total concept, infiltrated in all fields of knowledge, representation and communication – city is a pseudo-concept where all these plans are intercepted and all social facts are included – the political, economic, cultural, and technological dimensions, the visions of the world, the institutions, the daily life, etc. This infinite conceptual elasticity – for many a sign of the universality of the city through the combination of plasticity, diversity and generic forms and processes – would guarantee the persistence of the (supposed) clarity of the concept, despite the extreme cacophony of the contemporary urban fact. Paradoxically, this same elasticity acts as a conceptual shield that is both immune to epistemological criticism (which is, in fact, almost non-existent) and has a huge power of dissipation that allows easily moving the argument from one place to another in the infinite galaxy of things one speaks of when talking about the city, depending on how it best shapes this or that argument/characteristic of one city and another. At the same time, the statement of the essence of the city is confounded as many general characteristics of society and the process of modernization. Hence, its phenomenology is infinite.

The city would be eternal, transcultural and trans-historical – from Jericho of the sixth millennium to the gigantic megalopolis of the Pearl River Delta in China today – and so it survived (survives) at length to its own condition, becoming an ideological device associated with the European culture (more) or with the American culture (less):

“The urban is, then, an essentially contested concept and has been subject to frequent reinvention in relation to the challenges engendered by research, practice and struggle. While some approaches to the urban have asserted, or aspired to, universal validity, and thus claimed context-independent applicability, every attempt to frame the urban in analytical, geographical and normative-political terms has in fact been strongly mediated through the specific historical-geographical formation(s) in which it emerged – for example, Manchester, Paris and classically industrial models of urbanization in the mid-19th century; Chicago, Berlin, London and rapidly metropolitanizing landscapes of imperial–capitalist urbanization in the early 20th century; and Los Angeles, Shanghai, Dubai, Singapore and neoliberalizing models of globally networked urbanization in the last three decades.” (BRENNER, SCHMID, 2015).

It would be tedious to provide here a detailed explanation of the paradox between the depth of the changes of the urbanization process over time and the extremely diverse geography of this urbanization/modernization: the deepening of the commodification of goods and services and global capitalism; the primacy of technical-scientific rationality; the dilution of the cultural contrasts long fixed in their geographies and ethnographies.

In almost all cases, the vague concepts of city and urban have remained as a “regime of visibility” or truth, in the face of which everything that is known is positioned – a curious situation in which the error and the extreme imprecision of the concept distort the way of problematizing the real. The rural/urban dichotomy follows the same path with a no less confused and vague notion of rural and rurality, whether relative to the way of life, the cultural traits and visions of the world, the economy or the landscape. Even with the radicalization of the modernization of technologies, production processes and agricultural and agro- industrial markets, the rural remained vaguely as a poorly constructed, open, or natural territory/landscape (very false but also frequent).

Regime of visibility – way of seeing, representing and communicating what is known; to construct the meaning of reality, of the facts; to legitimize what is right and wrong, fictionalized, balanced, and fair; to set the standard and the deviation. It is Michel Foucault who uses the expression regime of visibility as a way of constructing/legitimising the truth, the conditions of enabling the truth through its inherent set of rules, practices and discourses. For Foucault, each society has its regime of truth: “the types of discourse which it accepts and makes function as true; the mechanisms and instances which enable one true and false statements, the means by which each is sanctioned; the techniques and procedures accorded value in the acquisition of truth; the status of those who are charged with saying what counts as true” (Michel Foucault, Dits et Écrits. Paris: Gallimard 1994, vol. IV, p. 112).

Reference authors – Frederic Jameson, Marshall McLuhan, Jean Baudrillard, Michel Foucault; Jacques Rancière; Gilles Deleuze; John Berger; Bruno Latour; Martin Jay (scopic regime)

Whenever the city as a way of seeing – name, form, centre and boundary – and as a self-contained organic system, was undefined and adopted terms that did not conform to this ideal type, soon there were ways of going around the question in such a way that the coherence of the whole, the primacy of form or the logic of the centred urban model were not lost, a centre that was simultaneously a place and axis mundi from which everything is organized and to which everything converges. The typical representation of the metropolitan area, for example, is that of a city that has expanded, (expand is the verb that is most used to describe urban growth/metamorphosis) while maintaining the centre/periphery model (or city/suburb), defined by both the contiguity of the built area and by a strong functional cohesion translated into the expansion of the residential dormitories in the periphery and the home/work commuting movements. In this and other new urban models, universal prototypes and archetypes were sought that might be applicable to Europe, the United States, São Paulo, and Bombay or to the impressive scale of urban China, referring to the most different frameworks of the modernization process, of global integration through the market, technology and culture, ranging from the archipelagos of prosperity to those of extreme poverty, from Paris or London of the nineteenth century to the late and radical modernity of Los Angeles at the beginning of the twentieth century, or to the infinite, diverse and contradictory mosaic of New Delhi – the same urbi et orbi urbanity.

From the inefficiency of the Metropolitan Area or the centred Metropolis or Megalopolis – an extensive urbanized spot characterized by a centre acting as the engine of this organization and expansion -, we now have the city-region, diffuse urbanization, multi-polarized conurbation or global urban mega- constellations.

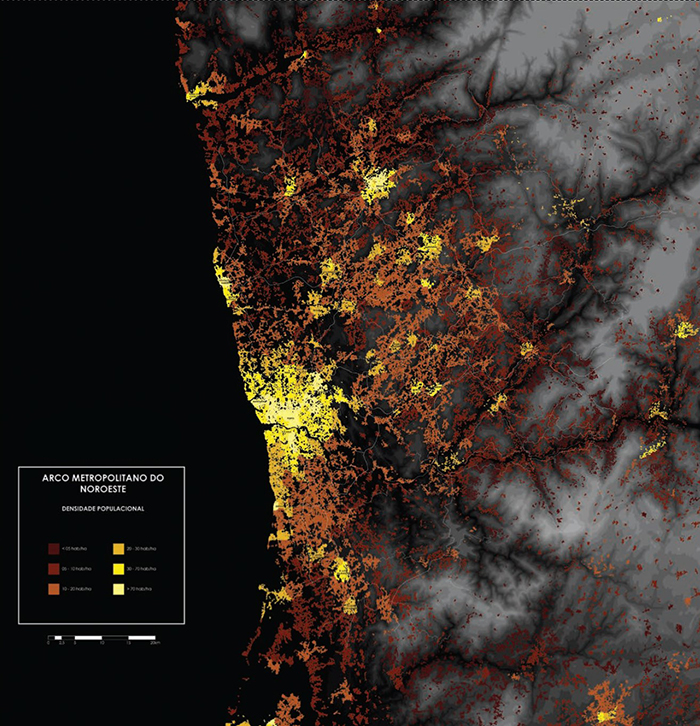

Fig.1. Urbanized Developed Northwest of Portugal – “Arco Metropolitano” (DOMINGUES, Álvaro; TRAVASSO, Nuno – coords., 2015).

As can be seen from this brief presentation of the urbanization model of Northwest Portugal [Fig. 1], the generalization of conceptual frames of reference and the urban imaginary of global metropolises and other great narratives were bound to be unsuccessful. From an empirical point of view, it is easy to see, at the same time, abysmal similarities and differences between urban contexts of similar scale in different places of the world; from a methodological point of view, to force urban analysis to the same categories and previous reference models – centre/periphery; planned/legal/informal; dense/dispersed, etc. – is a total mystification, even greater because it gives the illusion of objectivity by using similar analytical frameworks, common cartographic conventions, etc.

– the way of seeing creates what is seen; so, from an ontological point of view, this pseudo-objectivity based on mainly morphological readings and vague and generic social frameworks ends up making the distinct processes that produce what is called urbanization: completely opaque, unequal development, the commodification of urban space, the reproduction of poverty and exclusion, the way the state is involved in the global game of capitalism, and the complex social and governance models of China or India.

“Extensively urbanised interdependencies are being consolidated within extremely large, rapidly expanding, polynucleated metropolitan regions around the world to create sprawling “urban galaxies” that stretch beyond any single metropolitan region and often traverse multiple national boundaries. Such mega-scaled urban constellations have been conceptualised in diverse ways, and the representation of their contours and boundaries remains a focus of considerable research and debate. Their most prominent exemplars include, among others, the original Gottmannian megalopolis of “BosWash” (Boston-Washington DC) and the “blue banana” encompassing the major urbanised regions in western Europe, but also emergent formations such as “San San” (San Francisco-San Diego) in California, the Pearl River Delta in south China, the Lagos-centred littoral conurbation in West Africa, as well as several incipient mega-urban regions in Latin America and South Asia”. (BRENNER, SCHMID, 2014).

In Old Europe, works such as Metapolis by F. Ascher (1995), Zwischenstadt by T. Sieverts (1997), Città Diffusa by Indovina (1990), La Ville Franchisée by O. Mangin (2004), Splintering Urbanism by S. Graham and S. Marvin (2001), and many others, described the diversity of urbanization as a process – and not of the city as a morphological category and precise location – and of its multiple scales, densities, morphologies, fragments, or materials. The whole has been lost, the same applying to the sharpness of the limits and stability; the inoperability of the old urban/rural, city/territory dichotomies, or the correspondence between social systems and their respective spaces of reference – the city/constructed form would be the container of the city/social group – have been followed by quests for ways of problematizing the urban question. As Lefebvre had insisted since the early 1970s, the study of urban forms had to be informed by research of the urban processes at any spatial, global or micro-local scale. These processes produce, concomitantly, the multiplication of similarities everywhere (the generic city referred to by R. Koolhaas, 1996) and the exacerbation of differences.

“The urban and urbanization are theoretical categories. The urban is not a pregiven, self-evident reality, condition or type of space – its specificity can only be delineated in theoretical terms, through an interpretation of its core properties, expressions or dynamics. (…) While uneven spatial development is as intense as ever across places, territories and scales, the urban cannot be plausibly understood as a bounded, enclosed site of social relations that is to be contrasted to non-urban zones or conditions. Concomitantly, the urban/non-urban distinction is an obfuscatory basis for deciphering the morphologies, contours and dynamics of sociospatial restructuring under early 21st century capitalism. It is time, therefore, to explode our inherited assumptions regarding the morphology and territorial organization of the urban condition. The urban is not a universal form but an historical process that has become increasingly worldwide.” (BRENNER, SCHMID, 2014)

In the midst of this accelerated renewal by urban planners, geographers, sociologists and other classical disciplinary fields, there is an intense fragmentation and dispersion of Urban Studies with advantages in capturing various dimensions of urbanization through multi and interdisciplinary contributions, but reflecting, as in the previous case, the difficulty in positioning a minimally stable and consensual new paradigm of reference to occupy the role left by the intense crisis of the previous forms of problematizing the urban from the visual regimes dominant in Europe and the United States. Journals such as Urban Studies (Sage Journals) are a very diverse and rich setting for this multidimensionality of the urban fact, whether at empirical, theoretical or political level, reinforced by a permanent critical view that is very attentive to the “politically or technically correct” stance that dominates the scene: urban competitiveness, the smart city, the sustainable city, the inclusive city and so many other slogans that lend themselves to any mystification.

From this plurality of views and geographic frames of reference, one realizes that the deepening of the liberal capitalist system – called globalization – weakened the role of the state in social and urban regulation, instrumentalizing it and contributing to the fragility of conventional planning and urbanism, promoting other forms and instruments of intervention such as the Urban Project and special operations – sectorial or urban – with a strong involvement of private investment and its remit. It should also be borne in mind that “the state” is not close to being what is normally thought to be, nor at European level, much less in contexts such as Latin America, India, Africa or China, which also contain very large differences, even within the same country.

Of course there are many more reasons that explain the inefficiency of conventional planning and urbanism, because they are too dependent on the inertia of previous models; because of the lack of knowledge and practice in the face of permanent changes in the socio-technical systems that enable new urbanization patterns, which are extensive, discontinuous, of high or low constructive density, etc.; because it is quite erratic in the constant introduction of new designs and the so-called sustainable practices, sometimes oriented towards urban competitiveness and attracting capital – smart cities, innovation hubs, business areas and technology parks, large urban projects – and sometimes going back to the strong topics of the urbanism of the Social State – housing, services -; now and then becoming involved in the promotion of major events and urban marketing projects and actions; sometimes taking into account the historic city, requalification and reuse urbanism trends, the so-called soft modes of mobility, green urbanism and, generically, an endless number of political legitimization practices and forms that are geographically variable.

This collage of imaginaries and urban practices ranges from an evident commitment to social justice and an ideological framework that is manifestly liberal anti-capitalism and, on the other hand, to a total technological fetishization (the smart city) that is supposedly depoliticized – avoiding social conflict, polarities and exclusions, the game of interests of the priorities or of power of who over whom, etc. – where a generic common interest is taken for granted, an inevitability for the good of all mankind and free from discussion, and where the euphemistically called stakeholders simply stand.

These so-called post-political or post-democratic frameworks – because they have an absolutely technocratic and entrepreneurial nature – dilute the citizen, the user and the client in the same figure (people as a statistical category of vague, uncertain or absent social and political position), without involving debate, scrutiny, discussion about the distribution of powers, costs and benefits, priorities and ways of doing things. The technical principles of efficiency, organizational engineering, and utility are direct ways of legitimizing business, business-like urban management. On top of this chaotic ideological building stands sustainability – a good thing for business and the environment! – with its infinite rhetoric about how to balance everything that has never been articulated, as if the capitalist market and competition had ever had social justice ethics; as if democracy was being replaced by popular capitalism, or business was not capable of “greening” anything quickly turned into green and environmentally friendly (as long as it sells).

Almost all of this imaginary includes the dense and crowded city, shaped mostly by Western visions, fiercely criticizing not only urban dispersion and other models of settlement that do not fit in this preconceived image, but also the distinct mechanisms and processes of urbanization in diverse contexts, without any clear and positive strategy to address the issue, or even know it. Somehow, one of the most basic challenges of today is precisely to debate the process of urbanization in different territories and materializations – seeing the urban not as a form, but as a historical process – and specially to rethink the urban condition itself, redesigning the epistemological framework to observe and problematize it, to deconstruct its myths and rethink its aspirations. In other words:

“For this reason, we argue, the question of the epistemology of the urban – specifically: through what categories, methods and cartographies should urban life be understood? – must once again become a central focal point for urban theory, research and action. If the urban is no longer coherently contained within or anchored to the city – or, for that matter, to any other bounded settlement type – then how can a scholarly field devoted to its investigation continue to exist? Or, to pose the same question as a challenge of intellectual reconstruction: is there – could there be – a new epistemology of the urban that might illuminate the emergent conditions, processes and transformations associated with a world of generalized urbanization?” (BRENNER, SCHMID, 2014, p.155)

Indeed, the view of generalized urbanization is often confused with a general look at urbanization. In this sense, the analysis of the urbanization process, in its diversity and transformations, will be an important task not only to understand the phenomena that occur in each specific context – countering the adoption of homogenizing models under preconceived referents – but also to construct a much needed epistemology of the urban that confers the conceptual, critical and operative tools to deal with the current challenges and allows overcoming misunderstandings and impasses, both in how we see and manage these territories.

Accelerated urbanization

The process of intensification of urbanization in the last decades is well-known, as well as its corresponding asymmetry. However, the scale and impact of this urban explosion are not always really taken into account. In the Western context, the process of accelerating urbanization went hand in hand with industrialization and in parallel with the growth of industry and services, which meant the expansion of economic structures and job opportunities. And whereas in this context – although the process of urbanization has taken place in the most favourable conjuncture of economic growth – there has been a mismatch between the social requirements and the conditions created in the urban environment, in most of the territories in the South this disparity reached especially heavy proportions, with much higher rates of urbanization and greater economic fragility that translated into increased constraints to manage them.

It should be noted how, over a period of about five decades, while New York City doubled its population, other urban agglomerations multiplied their population several dozens of times [Fig. 2], with profound and marked effects regarding occupation area [Fig. 3].

Fig.2. Urban growth between 1950 and 2004 in several cities (based on DAVIS, 2006).

Fig.3. Urban growth in Manila, Philipines, between 1975, 1990 and 2010 (TAUBENBÖCK, ESCH, 2011).

At present, about a quarter of the urban population lives in conditions of extreme precariousness and an additional portion faces marked gaps in its habitat. Estimates suggest that this percentage has declined, but the numbers have increased, and the inequality of economic incomes will also have increased, especially in the economies considered to be more developed (UN-Habitat, 2008; OECD, 2011). Davis, in Planet of Slums (2006), and despite the apocalyptic tone of these transformations, gives some indications on this need to rethink the urban condition: presenting the city as the great project of humanity, he claims that we are currently at a critical and decisive point in urban history. He therefore asks whether the recent changes are a sign of a process of urban involution: a regressive movement, a return to conditions that had already been overcome in the past, constituting a model of territorial organization that may not translate into equivalent quality of life of its citizens, opposing the usually conveyed idea of urbanity and that cities would be centres of concentration of resources and opportunities. On the contrary, recent dynamics have demonstrated not only that urban growth is not directly related to economic growth, but also that spatial concentration is not necessarily motivated by the attractiveness of urban areas, but by an escape from even greater deprivation conditions.

Thus, in the face of the most diverse scales and spatializations of these urbanization processes – from the southern megacities and the conurbations and constellations that form urban continuums to the “urbanization in loco” (DAVIS, 2006) of areas previously marked by a rural matrix, the more recurring models of observation – tendentially antagonistic and bipolar – are not adequate:

“In the study of these current societies, the neglected use of bipolar categories and analytic concepts with mutually exclusive or antagonistic urban/rural, modern/traditional, centre/periphery, formal/informal, capitalism/socialism, individualism/solidarity poles run the risk of skewing the analysis. It is, in fact, one of the characteristics of Western scientific perception and common sense of approaching society (and not only) according to this bipolar prism.” (OPPENHEIMER, RAPOSO, 2007).

And if this is true in the European and American context – where urban historiography entails a legacy of observation of space transformation processes -, in the South this difficulty arises even more explicitly, hampered by the speed of mutation, by the impact of global capital, by the overlapping of different logics and also by the import of exogenous ways of looking, where – even more radically – the mismatch of the usual bipolar explanatory models of the world and the search for common denominators can be seen (ROY, 2009). The discourse on African cities is especially paradigmatic not only of the complexity of the transformation processes of societies and their spaces, but especially of the limitations of the preconceived stances corresponding imaginaries:

“In the post-colonial African situation, simultaneity, “permanence and rupture” (according to Coquery Vidrovitch’s work of reference, 1985), the overlaps, mestizo and DIY (Marie, 1998), the dynamic and permanently changing combinations of ideologies, values, practices, technologies, with endogenous/exogenous, rural/urban, African/western, symbolic/material elements, the world of the dead and the world of the living predominate. This feature frustrates any attempt at decoding and interpreting the present African urban society that is based on traditional representations, theories and methodologies available to the western social and urban sciences.” (OPPENHEIMER, RAPOSO, 2007)

Thus, when the interpretation of these contexts is limited by gaps in the way of looking at and understanding the specificities and transformations of these territories, these mistakes also have repercussions at the level of the action mechanisms, namely the design of intervention policies, the definition of priorities and strategies, which is one of the structural reasons why some of the disparity reduction programmes may have results that fall short of expectations. Faced with diagnostic gaps, the “approximative therapy” (Fanon, 1969) is recurrently used, deferring structural solutions and perpetuating the most critical situations.

For this reason, one of the most urgent tasks to be undertaken lies precisely in the return to the most basic point of discussion of the urban condition and in understanding recent urbanization: to observe and analyse the process in its complexity and diversity, as well as to discuss and re-conceptualise the conceptual and operational tools – to build the epistemological framework – to understand and manage the new socio-spatial challenges.

The ‘Urbanization of Poverty’ – MiArq-FAUP course unit

It is precisely in the context of this need to look and discuss in greater depth the socio-spatial challenges of the urbanization process and the resulting disparities that the ‘Urbanisation of Poverty’1 course unit was created at the Faculty of Architecture of the University of Porto (FAUP), aimed both at the training of students and young professionals in this area of architecture and urbanism, and to encourage a broader discussion of this theme, open to new audiences and civil society in general, through open classes, conferences, round tables, and talks.

Thus, perceiving academic institutions as spaces for the training of technicians and also for building a civil conscience, it seeks to contribute to the construction of new ways of looking and acting, more attentive to the asymmetries of the urbanization process and the social role of the different actors intervening in this process of managing and transforming the built environment.

The debate on equity is a global issue affecting countries both in the North and in the South, and the role on the built environment for more equitable spaces and democratic access to urban resources is increasingly a challenge for architects and town planners. More than just studying the geography of these phenomena – or the evidence of their symptoms – it is a question of seeing them as a sign of alarm and urgency of the need to rethink the urban condition, as well as the role of the state and of the different agents that shape the built environment. From this perspective, the aim is to reinforce theoretical and practical discussion around the spatialization of poverty and the disparities in this urbanization process, as well as the social concerns in the disciplinary field of architecture and urbanism, through not only discussing the disparities and/or limitations of resources, but also framing the multiple actor management mechanisms. In fact, in contexts of marked precariousness, where not only the public capacity to intervene in the built environment is limited by deep economic and material constraints, as this action ends up being complemented by several actors (international agencies, organizations and associations, residents), the professional practice of the architect/urban planner is rarely placed solely in a relationship between client and service provider; on the contrary, there are several actors in the decision-making process, placing the architect/urban planner in the role of mediator and facilitator.

This course unit is structured around three sets of concerns: exposed poverty – showing urban expansion in the South -, covert poverty – geared to emerging economies – and assisted poverty – especially directed to the Western context, analysing the construction and transformation of the welfare state. Rather than presenting a historical view of the different approaches to urban and regional planning, the aim is to provide students with tools for interpreting and problematizing deeply contrasting contexts, reinforcing critical awareness of global asymmetries while strengthening the skills that enable facing professional challenges in the context of scarcity.

Parallel programming – through open classes, conferences, talks and debates – is, on the one hand, a space for sharing professional and research experiences, involving guests who have recently studied or participated in development projects, with special attention paid to Portuguese-speaking territories; on the other hand, it is also an opportunity to broaden the discussion of these concerns to a wider audience by promoting complementary learning spaces and extending the debate to the scientific community and civil society.

Final remarks

While the built environment does not in itself determine the social condition of those who live in it, it is equally true that it is not completely alien to it. So the debate on the urban condition – in particular its asymmetries and the so-called “urbanization of poverty” – will in itself be not only a broad responsibility – of technicians towards civil society, of students towards professionals and institutions – but also a useful task for strengthening awareness and the prospect that efforts to mitigate disparities can be strengthened and more effective.

Bibliography

ASCHER, François – Métapolis ou l’avenir des villes, Paris: Odile Jacob, 1995. ISBN 978-2738103178.

BENNER, Neil; SCHMID, Christian – “Towards a new epistemology of the urban?”, City, 2015, Vol. 19, nos 2-3, Londres: Routledge, 2015, pp.151-182.

BRENNER, Neil; SCHMID, Christian -“The ‘Urban Age’ in Question”. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38 (3), 2014, pp.731–755.

BRENNER, Neil, ed. – Implosions/Explosions: Towards a Study of Planetary Urbanization. Berlim: Jovis, 2014. ISBN 978-3-86859-317-4.

BRENNER, Neil; MARCUSE, Peter; MAYER, Margit, eds. – Cities for People, Not for Profit: Critical Urban Theory and the Right to the City, Nova Iorque: Routledge, 2012. ISBN 978-0415601788.

BURDETT, Ricky; SUDJIC, Deyan – The Endless City. Londres: Phaidon, 2006. ISBN 978-0714859569.

CALTHORPE, Peter; FULTON, William, The Regional City, Washington D.C.: Island Press, 2001. ISBN 978-1559637848.

CASTELLS, Manuel – The Urban Question: A Marxist Approach. Cambridge, Massachussetts: MIT Press, 1977, orig.1972. ISBN 978-0262530354.

COQUERY-VIDROVITCH, Catherine – Africa: endurance and change south of the Sahara. Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1988, orig.1985. ISBN 978-0520078819.

CORREA, Charles – The new landscape: Urbanization in the Third World. Oxford: Butterworth Architecture, 1989. ISBN 978-0408500715.

DAVIS, Mike – Planet of slums, Nova Iorque: Verso, 2006. ISBN 978-1844671601.

DOMINGUES, Álvaro; TRAVASSO, Nuno, coords. – Território: Casa Comum, Porto: Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto, 2015. ISBN 978-9898527073.

FANON, Frantz – Em defesa da Revolução Africana. Lisboa: Livraria Sá da Costa Editora, 1980, orig.1969.

FILGUEIRAS, Octávio Lixa – Da Função Social do Arquiteto: para uma teoria da responsabilidade numa época de encruzilhada. Porto: E.S.B.A.P. – Arquitectura, 1985, orig.1962.

GARCÍA-HUIDOBRO, Fernando; TORRITI, Diego Torres; TUGAS, Nicolás – ¡El tiempo construye! El Proyecto Experimental de Vivienda (PREVI) de Lima: génesis y desenlace / Time builds! The Experimental Housing Project (PREVI), Lima: genesis and outcome. Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 2008. ISBN 978-8425221958.

GRAHAM, Stephen; MARVIN, Simon – Splintering Urbanism: Networked Infrastructures, Technological Mobilities and the Urban Condition, Londres e Nova Iorque: Routledge, 2001. ISBN 978-0415189651.

HARVEY, David – “Cities or urbanization?”, City, 1, pp.38–61, 1996.

HARVEY, David – Rebel Cities. London: Verso, 2012. ISBN 978-1781680742.

HAMDI, Nabeel – Housing without houses: participation, flexibility, enablement. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1991. ISBN 978-0442001612.

HAMDI, Nabeel – Small Change. About the art of practice and the limits of planning in cities. London, Sterling VA: Earthscan, 2004. ISBN 978-1844070053.

HATCH, Richard, ed. – The scope of social architecture. Nova Iorque: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, 1984. ISBN 0-442-26153-5.

INDOVINA, Francesco – La Città Diffusa, Veneza: Istituto Universitario di Architettura di Venezia. Dipartimento di Analisi Economica e Sociale del Territorio, 1990.

KOOLHAAS, Rem; OMA – The Generic City, TN Probe, 1996. ISBN 1-885254-86-5.

KOOLHAAS, Rem; BOERI, Stefano; KWINTER, Sanford; TAZI, Nadia; OBRIST, Hans-Ulrich – Mutations, Bordeaux: Arce n Rêve – Centre d’Architecture; Barcelona: Actar, 2000. ISBN 978-8495273512.

LEFEBVRE, Henri – Le droit à la ville. Paris: Éditions Anthropos, 1968. ISBN 978-2717857085.

MANGIN, David – La ville franchisée: formes et structures de la ville contemporaine, Paris: Editions de la Villette, 2004. ISBN 978-2903539757.

MASSEY, Doreen – For Space. London: Sage, 2005. ISBN 978-1412903622.

OECD – Divided We Stand: Why Inequality Keeps Rising. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2011. ISBN 978-9264111639. URL: http://www.keepeek.com/Digital-Asset-Management/oecd/social-issues-migration-health/the-causes-of-growing-inequalities-in-oecd-countries_9789264119536-enpage1, acedido a 14 de abril de 2016.

OPPENHEIMER, Jochen; RAPOSO, Isabel – Subúrbios de Luanda e Maputo. Tempos e Espaços Africanos. Lisboa: Edições Colibri, 2007. ISBN 978-9727727605.

PAVIA, Rosario – Le paure dell’urbanistica, Roma: Meltemi, 2005, orig.1996. ISBN 978-8869164910.

ROY, Ananya – “Urban Informality: Toward an Epistemology of Planning”, Journal of the American Planning Association, 71:2, 2005, pp.147-158. ISSN 1939-0130.

ROY, Ananya – “The 21st-Century Metropolis: New Geographies of Theory”, Regional Studies, Vol. 43.6, pp. 819–830, julho 2009. ISSN 1360-0591.

ROY, Ananya; ONG, Aihwa, eds. – Worlding Cities: Asian Experiments and the Art of Being Global. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012. ISBN 978-1405192767.

SERAGELDIN, Ismaïl, ed. – The Architecture of Empowerment: People, Shelter and Livable Cities, Londres: Academy Editions, 1997. ISBN 978-1854904935.

SIEVERTS, Thomas – Cities Without Cities: An Interpretation of the Zwischenstadt, Londres: Routledge, 2003, orig.1997. ISBN 978-0415272605.

SIMMEL, Georg – “The Problem of Sociology”, American Journal of Sociology, Volume 15, nº3, 1909, pp.289-320. URL: http://www.d.umn.edu/cla/faculty/jhamlin/4111/ Readings/SimmelProblem.pdf, acedido a 16 abril 2016.

SOJA, Edward; KANAI, Miguel – “The Urbanization of the World”, in BRENNER, Neil, ed. – Implosions/Explosions: Towards a Study of Planetary Urbanization, Berlin: Jovis, 2014, pp.142–159. ISBN 978-3868593174.

TÖNNIES, Ferdinand – Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft, Leipzig: Fues’s Verlag, 1887. Edição inglesa: TÖNNIES, Ferdinand; LOOMIS, Charles Price – Community and Society, Courier Corporation, 1957. ISBN 080-0759424979.

TAUBENBÖCK, Hannes; ESCH, T. – “Remote sensing – An Effective Data Source for Urban Monitoring”, Earthzine, 2011. URL: http://www.earthzine.org/ 2011/07/20/remote-sensing%E2%80%93-an-effective-data-source-for-urban-monitoring/, acedido a 13 de abril de 2016.

TURNER, John F.C.; FICHTER, Robert, eds. – Freedom to build. New York: Macmillan, 1972. ISBN 978-0020896906.

TURNER, John F.C. – Housing by people. Towards autonomy in building environments. Nova Iorque: Pantheon Books, 1977. ISBN 978-0714525693.

UN-Habitat – State of the World’s Cities 2010/2011: Bridging the urban divide. Londres: Routledge. United Nations Human Settlements Programme. 2008.

Urban Theory Lab – Extreme Territories of Urbanization. Research report. Cambridge, Massachussetts: Urban Theory Lab, Graduate School of Design, Harvard University, 2015.

VIARD, Jean – La société d’archipel, ou les territoires du village global, La Tour d’Aygues: L’Aube, 1994. ISBN 978-2876781696.

VELTZ, Pierre – “Mondialisation, villes et territoires: L’économie d’archipel”, Politique étrangère, vol.61, nº2, pp425-426. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1996.

WEBBER, Melvin – “The Urban Place and the Nonplace Urban Realm”, in WEBBER, Melvin – Explorations into Urban Structure. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1964. ISBN 978-0812274158.

WEBER, Max – Collected Essays in the Sociology of Religion, vols.1-3. Edição original: Gesammelte Aufsdtze zur Religionssoziologie, 1921.

WACHSMUTH, David – “City as ideology: reconciling the explosion of the city form with the tenacity of the city concept”, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, volume 31, 2014, pp.75 – 90.

WIRTH, Louis – “Urbanism as a way of life”, The American Journal of Sociology, vol.44 (nº1): 1938, pp.1-24.

1 This course unit is the responsibility of Álvaro Domingues, a geographer and Associate Professor at FAUP, and has the scientific and organizational collaboration of Ana Silva Fernandes, architect and researcher at the Morphologies and Dynamics of Territory (MDT) group of the Centre for Architecture and Urbanism Studies of the same institution (CEAU-FAUP), in a close relationship between teaching and research.